It’s a special thing to find books that speak to or parallel our spiritual, religious or cultural identities. Books with characters who sound like our most beloved Jewish relatives. Books that connect us to Jewish practices when we’re a bit lost. Books that simply feel Jewish in sensibility or humor. Books that show us what’s possible as people — and as writers.

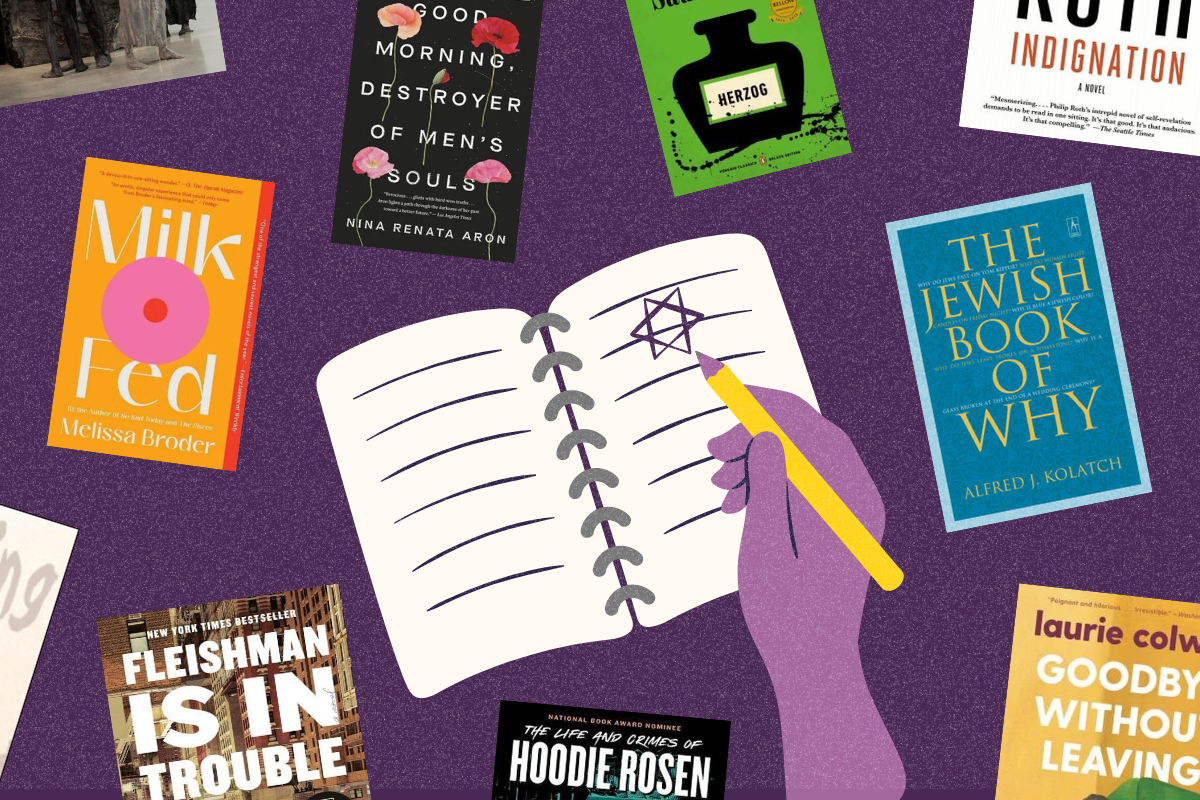

I asked 11 Jewish writers who have publications out or forthcoming this year to highlight a book that shaped their Jewish identity, writing craft or both. Their responses intersected with so many other identities, and were both heart-warming and hilarious. From novels to poetry to collections to the Talmud itself, these are recommendations you’ll want to visit or revisit, alongside the vibrant work of these Jewish authors.

Courtney Sender, author of the short story collection “In Other Lifetimes, All I’ve Lost Comes Back to Me”

Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s “Fleishman Is in Trouble” is a masterclass in playing at the edges of what a first-person narrator can know. Fiction is always an exercise in pushing the bounds of reality, getting at a psychological or spiritual or social truth by shaping reality in ways it isn’t shaped, and the first-person in “Fleishman” definitely pushes those bounds. Unlike, say, Roberto Bolaño’s “Distant Star,” which shows the documentary evidence through which the narrator reconstructs the story, “Fleishman” simply instantiates that the narrator knows the intimate inner life of her friend. I love that Brodesser-Akner dares to push the realist bounds of perspective in a book that’s otherwise fully grounded in realism.

Jewishly, there’s something almost midrashic to me about how “Fleishman” (spoiler alert!) retells what’s come before from the woman’s perspective. The recognition that stories depend on their interpreter, that they can be reinterpreted and deepened and re-understood, feels fundamentally Jewish in sensibility. The text may be set in stone, but its meanings and implications are not; a good story requires and is rich enough to sustain deep inquiry and multiple interpretations.

Adam Mansbach, author of the novel “The Golem of Brooklyn”

I’m a month into something called Daf Yomi, which is the practice of studying one page of the Talmud a day; the entire process takes seven and a half years, and I’m doing it with my friend Natalia Mehlman Petrzela (author of the excellent “Fit Nation”).

I realize I’m a little bit like the guy who joins the gym on New Year’s Day and then extolls the wonders of exercise throughout January, but I’m finding the daily practice of close reading and discussion incredibly rewarding. I always knew the Talmud was this endless, all-encompassing conversation across generations, this document that embodies so much of the essential character of the Jewish people and explains everything from our acumen for the law to the expression “Two Jews, three opinions” — but I knew it in the abstract. Actually parsing the text takes you to all sorts of wild places; it offers insight into the structure of society and the moral concerns of the rabbis; it shows you the wide-ranging, cross-referential, democratic approach the discussants take to confronting every aspect of the law; it forces you to rethink much of what you know about narrative structure, scene and character. Perhaps most of all, it encourages you to sit with ambiguity; seldom is an issue definitively resolved, but it is always examined via metaphor and scripture and case study, from multiple perspectives, and with a sense of the absolute importance of the deliberative process.

There’s also something cool about knowing that we are engaged in a process that is thousands of years old — that is not just a through-line in the history of our people, but one of the main reasons we’re still here. But, you know, ask me again in a year or two.

Fancy Feast, author of the essay collection “Naked: On Sex, Work, and Other Burlesques”

I was handed a copy of Joy Ladin’s monograph, “The Soul of the Stranger: Reading God and Torah from a Transgender Perspective,” by the author herself at a time when I was having a hard time contextualizing my relationship to formal Jewish practice. In the book, Joy, the first openly trans professor at an Orthodox yeshiva, retells Torah stories I’d grown distant from, imbuing them with intimacy and clarity, rightfully situating a relationship with God beyond any cultural norms of a gender binary. She deftly weaves together personal experience and autoethnography with close readings of religious texts, synthesizing the two to enhance the reader’s understanding of both. This style of writing allows for multiple pathways in for readers, which I really needed as someone who feels alienated from scripture.

I kept that in mind when I was writing my own book, which is fun and sexy, and also deals with challenging topics pertaining to sex and gender. Rather than omitting one way of being in service of the other, I felt more equipped to embrace a co-existence after reading her book! What a gorgeous gift to receive.

Ruth Madievsky, author of the novel “All-Night Pharmacy”

When I first read “Milk Fed” by Melissa Broder on the heels of completing my debut novel, I briefly wondered if I’d travelled back in time to plagiarize it. It felt as though Broder had stuck a froyo spoon in my ear and scooped out the part of my brain that wrestles with generational trauma, Jewish mysticism and life as a semi-secular, observant-curious Jew. Through a darkly comedic lens that feels distinctly Jewish (I can practically hear my relatives describing a restaurant, as Broder does, as having “a farm-to-hell look that always made me think of death by hanging”), the novel follows 24-year-old Rachel as she navigates her lust for a young Orthodox woman who works at her local frozen yogurt shop. I dog-eared the shit out of this book when I reread it while revising my novel. Who is writing hotter sex, funnier sentences and a more chaotically authentic exploration of Jewishness (“I felt guilty using my grandmother’s favorite song to animate a penis,” Rachel thinks while masturbating on an exercise bike to the tune of a Hebrew blessing) than Melissa Broder? Literally no one. I will always think of “Milk Fed” as my novel’s cool older cousin, or, if I’m really flattering myself, someone my novel might have hooked up with at Jewish summer camp.

Jiordan Castle, author of the young adult memoir-in-verse “Disappearing Act: A True Story”

I can’t say enough good things about Nina Renata Aron’s “Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls: A Memoir of Women, Addiction, and Love.” So often I struggle to find books, let alone memoirs, that demonstrate the everydayness of being a culturally Jewish woman — the language we inherit, our collective memory and the beauty standards we’re forced to reckon with over and over. That, and she so brilliantly, so beautifully, explores the line between closeness and codependency in families where an elephant is permanently positioned in every room of the house. To me, this book is perfect. I felt brave and held as a Jew reading it, for all of our coastal and familial parallels, and inspired to be more ambitious in my own work as a result.

Daisy Alpert Florin, author of the novel “My Last Innocent Year”

Growing up, my father was my primary literary influence. The author he recommended most fervently and often was Philip Roth, whose work he felt most clearly captured the essence of his postwar Jewish upbringing. “Indignation,” Philip Roth’s 29th novel, tells the story of Marcus Messner, the son of a kosher butcher from Newark who hopes to wait out the Korean War at the fictional Winesburg College. I first read it when I was in the early stages of drafting “My Last Innocent Year,” and its influence on my work is clear: his focus on working class Jews, his preoccupation with sex and class as well as the tensions between immigrant parents and their children, and perhaps most of all the question of what assimilation costs Jews. Roth also inspired me to set my novel at a distinctly American cultural moment — the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal — and gave me permission to let historical forces intrude on the narrative.

Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach, author of the poetry collection “40 Weeks”

Emigrating to the U.S. from Dnipro, Ukraine when I was 6 years old, I was raised on the silver-age Russian-language poetry of Anna Akhmatova, Osip Madelstam and Aleksandr Blok, carrying their music with me. But only when I read Ilya Kaminsky’s “Dancing in Odessa,” in the first year of my MFA, did I actually hear this music sing in the English language. Kaminsky showed me how the ghosts and soil of our past haunt the present through lyrical poems anchored in a strong narrative backbone. My early poems were in conversation with his without even realizing it, simultaneously building a metaphorical landscape out of the landscape across the water, which we both left, in the same year, and for the same reason — as Jewish asylum seekers.

In the collection’s opening poem, “Author’s Prayer,” he writes: “If I speak for the dead, I must leave/this animal of my body,/I must write the same poem over and over,/for an empty page is the white flag of their surrender.” This is an urgent call to keep writing, obsessively, about a traumatic history and present, because to write, to sing, to carry intergenerational memory into verse, keeps it living for the generations who follow. Amid the unimaginable war against our birthplace, Kaminsky is translating and lifting up Ukrainian voices who endure and create in the face of devastation, no white flags in sight.

Ben Purkert, author of the novel “The Men Can’t Be Saved”

A lot has been said about the link between Judaism and neuroticism, but nobody has said it better than Saul Bellow. In his landmark novel “Herzog,” we enter the mind of a protagonist suffering from anxiety in the extreme. Moses Herzog is going through a stressful divorce and feeling “the thread of life… stretched tight.” Reading this novel, I found myself deeply compelled by his predicament; it was both moving and — If I’m being honest — kinda hilarious to experience his mental strain second-hand. As I began work on my own novel, I kept “Herzog” close. It was a reminder of how a character’s neuroses can serve a narrative, and how the best Jewish humor is frequently born out of moments of great personal strife.

Dahlia Adler, author of the young adult novel “Going Bicoastal”

Writing about religion when it’s such a huge part of your life is an incredibly fraught, tricky thing, especially when you’re in a small denomination of a minority religion. Reading Isaac Blum’s knockout debut, “The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen,” felt not only deeply true to my personal experiences, but unsettling. Exposing. It showed me a way to explore the difficult balance of sharing both the beauty and ugliness of an insular community, and how to write a book that worked for an outside audience while still feeling like it was written for you and your people. It was something I’d seen a Muslim YA author (S.K. Ali) do beautifully, but had never seen done well in a Jewish book, and then to see it receive the incredible reception it did was just wonderfully validating and inspiring. I don’t know that it’s something I could emulate yet, but it meant a ton to me just to know it was possible.

Hilary Zaid, author of the novel “Forget I Told You This”

Laurie Colwin’s “Goodbye Without Leaving” is one of my favorite novels of all time. It is the apotheosis of a voice-driven literary novel about what it means to be a precise and specific human being at a precise and specific moment in time. Colwin’s narrator happens to be a Jewish person living what I think is a very typical late-modern American Jewish life: assimilated, non-observant, culturally Jewish. In fact, the first movement of the book is initiated when the narrator, Geraldine Coleshares, gets dressed up and “in a fit of longing” creeps into the back of the synagogue for High Holy Day services. Not understanding a word of Hebrew, she goes off on a rock ‘n’ roll listening binge “to ease her soul” and her dreams come true. A Jewish longing and a Jewish sensibility is thread through this entire novel, which is about chronicling a lost cultural legacy. This is exactly the kind of Jewish novel I have hoped to write, very much akin to the kind of queer novel I have hoped to write: a novel in which a marginal identity is wholly normative and as transparent and all-encompassing as air — and as essential, too.

Jennifer Fliss, author of the short story collection “As If She Had a Say”

When I think of an influential book, I think of “The Jewish Book of Why” by Alfred J. Kolatch — both as a human and a writer. It’s a big book asking questions like why don’t Jews eat shrimp? (I do.) Why do we break glass at a wedding ceremony? (Did that.) It’s like Jewish 101, but less about the rules of being Jewish and more about asking the why behind those rules and social norms. Questioning, not knowing the answer, reading for facts or clues about why humans are the way we are — this is why I write. Why does this have to happen? Why not? What’s the history of this particular ritual or habit? Why does this character do that? Being Jewish is intrinsic to me as a writer; every story I write is like a section from “The Jewish Book of Why.”