“Our dear Hannah, Mom and Dad never gave up on you.”

Those are the words written on the poster board my aunt holds up at the protest of the Yemenite Children’s Affair — a far too nice description for the atrocity that was the state-sponsored kidnapping of Yemenite babies from their parents in the early years of Israel’s independence. The Yemenite Children’s Affair is a stain on Jewish history that is largely unknown to people outside of Israel.

My aunt, related to me by marriage, has attended the annual protest held outside the Knesset in Jerusalem for the last seven years with her siblings. This past summer, my sister and I join them. On the long bus ride to Jerusalem, my aunt tells us how she is fighting her parents’ fight.

Shortly after arriving in Israel from Yemen in 1949, their baby girl Hannah was taken from them. She was their second child, born in Yemen and only eight months old when the family made aliyah. She was eleven months old when she was abducted and reported dead by the government. My aunt tells me that she remembers her parents crying every single day for their lost daughter; they would see her in every Yemeni girl around the same age.

Growing up, my aunt admits, she thought her mom was delusional. She thought her mom had imagined Hannah, the big sister they never got to meet. But on Hannah’s 18th birthday, their family was sent Hannah’s mandatory draft letter for the army. This confirmed that Hannah did in fact exist — and was very much alive. It was salt in a wound that never healed. Over the years, my aunt’s parents tried everything and looked everywhere for Hannah. They wrote letters, protested, and petitioned the government, but they died without seeing Hannah again.

This isn’t just a sad personal story or an isolated incident. It was systemic. My aunt’s family’s circumstances are similar to those of thousands of other Yemenite Jews who fled their homes for the new Jewish state.

For so many Yemeni Jews, it’s the same story with different details: An “official” government, healthcare or social service worker would take a baby from a family under the pretense of providing them with temporary care, shelter or health screenings. The parents of the children, who arrived from Yemen exhausted and desperate, were trusting of the same institutions that had just saved them from persecution. Most didn’t even have the language to ask questions.

And when the parents would return for their child, they would receive the news that the child had died. The child was gone. Sometimes the parents were given a forged death certificate, but never an actual body. There are countless Yemeni Jews who have either lost someone this way or know someone who has.

From there, it gets blurrier. Some kids were funneled into the foster system to be adopted by childless European Jews in Israel and the United States. Allegedly, some of these were Holocaust survivors who lost their own children or who were rendered infertile because of the atrocities committed against them.

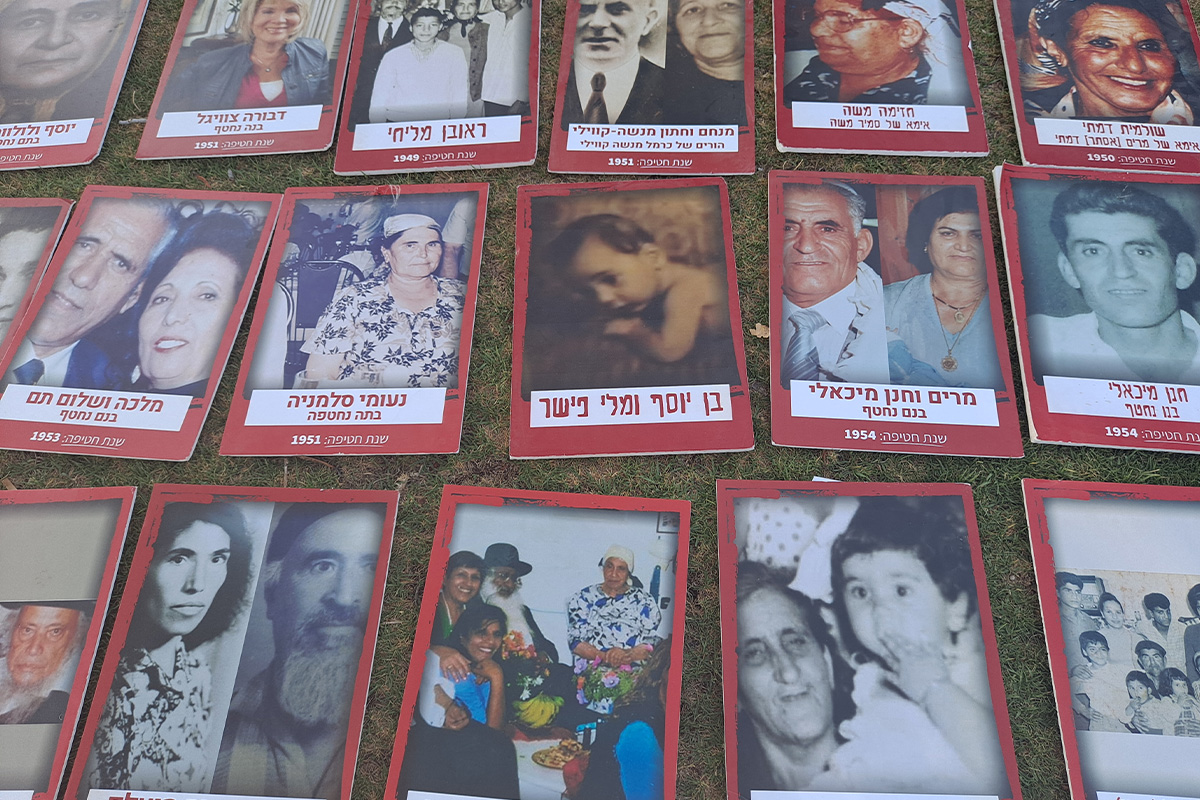

At the protest, I am overwhelmed by all the voices. One man screams about the gaslighting, how they turned our grandparents into crazy conspiracy theorists. Another woman cries that they snatched her newborn from her breast as she nursed him. Some feel compelled to speak truth to their pain, while others have been scarred into silence. Some blame specific organizations and politicians and some blame the entire government, but all demand answers.

The point of the protest, year after year, is to make it clear that the victims refuse the restitution that has been offered to them in exchange for their silence. The demand is for the Israeli government to hand over the documents they have on these children and their whereabouts. And at the bare minimum, they want the Israeli government to take responsibility for their crimes.

In the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, the freshly formed Israeli government saw the new flood of Yemenite immigrants as “primitive.” They feared they didn’t have the education, resources or capacity to properly care for their many children.

My mom, born in Israel to Yemeni parents, admits that conditions were terrible, that some of the motives for these horrific acts originally stemmed from legitimate concerns and good intentions. These things can be true — yet they justify nothing. Abducting children from their parents and leaving them with empty graves to cry over is never justified.

Like my aunt’s parents, my mom’s parents arrived in Israel from Yemen in 1949 on a rescue mission called Operation Magic Carpet — a name that connotated fairy-tale heroism in my mind. Growing up, I imagined my grandma and grandpa setting foot in a paradise of promised land.

The truth, I’ve since learned, is a much bleaker, much harsher refugee absorption camp Yemenite families crowded into.

My uncle, my grandparents’ first born, was delivered in one of these makeshift cities. He tells me he got sick as a young boy and spent a long stretch at the hospital. He remembers that my grandpa never left his side during this time — refused to. My uncle jokes that he was the kind of kid his parents should have been worried would be taken from them, all bright-skinned and beautiful. We laugh now, but we know it’s the furthest thing from funny.

Yemeni Jews are said to have “simchat chaim,” which translates to “joy for life.” I have always felt that to be true. Growing up, the days with my Yemeni family in Israel were spent eating, singing, dancing and laughing. This was how I understood my Yemeni heritage: through the lens of joy, humor and celebrations. It was only this summer, standing and shouting among grieving protestors, that I truly understood the deep pain and trauma rooted in Yemenite Jewish history.

When I spoke to one of the organizers of the protest, she credited this year’s low turnout to siblings and parents getting older. That’s why it’s been so important to involve the younger generations, the children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren who can carry on the work most parents took to their deathbed.

That’s why I am getting involved now: to fight for my aunt’s lost sister and to help raise awareness about what happened all those years ago.

I debated my decision to write this article. At a time when antisemitic hate crimes are at an apex in America and around the world, I didn’t want to somehow contribute to that. I didn’t want to give ammunition to antisemitism disguised as anti-Zionism. However, let this article be proof: It’s possible to criticize the Israeli government without being antisemitic. It’s just easier for some people to vilify Jews than to do the hard work of delving into history, specifics and uncomfortable complexities. My aunt and her siblings protest as Yemenites and as Israelis. While Israel has come a long way from its past marginalization of Mizrahi citizens, this issue has yet to be formally addressed and rectified. And this story needs to be told because it’s true, it happened and there are still people suffering because of it.

Although there have been a few reunions between stolen children and their families over the decades, many, like my aunt, admit that they don’t anticipate finding or reuniting with their loved one. They simply want — need — it to be known that they never stopped looking.

So Hannah, wherever you are, whoever you may be now, your family never gave up on you.

For more information, the Amram Association (https://www.edut-amram.org/en/the-kidnappings/) is an organization that leads the charge for the recognition and investigation of the kidnappings and has been responsible for locating separated families and bringing them back together. The information on the website can be translated into English.