When I spoke to literary critic Ruth Franklin earlier this year about the new Anne Frank exhibition in New York City, she said her hope for visitors was that walking through full-scale recreations of the annex rooms “brings them back to the existence of Anne Frank as a real person.”

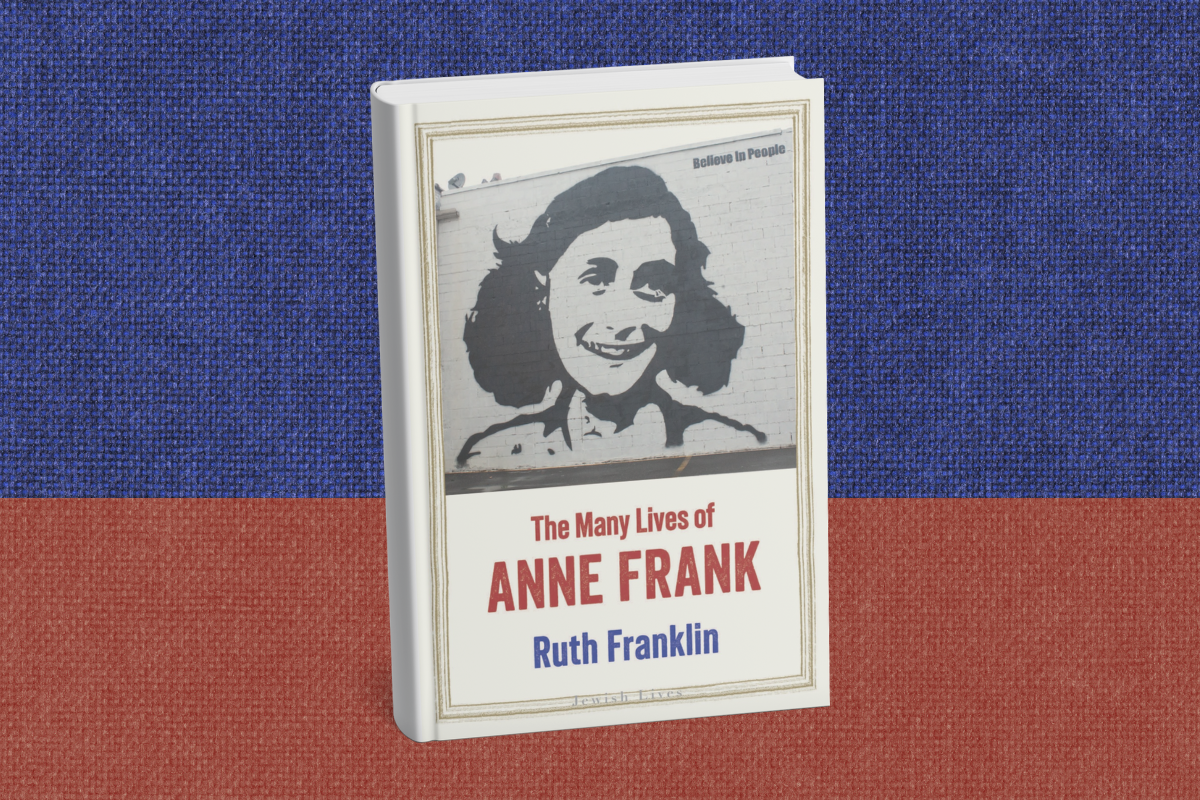

There are tens of millions of copies of Anne’s famous “Diary” in print in dozens of languages, with stage and screen adaptations galore. “Everybody knows the story of Anne Frank,” Franklin told me over the phone more recently. “Or they think they do.” But Anne’s name and image have become so ubiquitous that we’ve lost sight of the young woman and artist behind them, Franklin argues in her new biography “The Many Lives of Anne Frank.”

It’s on this note that she begins and ends her book. “Anne’s transformation into an icon has had the effect of obscuring who she really was. She becomes whoever and whatever we want her to be,” Franklin writes in the introduction. “I strive to return Anne to herself, restoring her as a human being.”

Franklin explores Anne’s many identities in roughly chronological but fundamentally thematic chapters on Anne before and after her death — as a child, refugee, target, witness, lover, artist, prisoner, corpse, author, celebrity, ambassador, “survivor” (as imagined in fiction) and pawn. She concludes with a final plea that we remember her also “as a teenager behind a locked door, pen and paper at the ready: watchful, indomitable, alive.”

Franklin spoke with me about how this objective came to undergird the biography, what we’ve gotten so wrong about Anne and the “Diary” for so long and what we stand to gain by seeing Anne as a person rather than an icon.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

By the time you were eight, you’d read the “Diary” and visited the Anne Frank House. Can you tell me about this early interest?

I grew up in a family of survivors, so the Holocaust was always very present in our lives. I grew up listening to my grandparents’ stories. Anne — for me as for so many Jewish girls — was somebody who was extremely relatable in that she goes through so many of the things that ordinary teenagers do, and yet this unfathomable thing happened to her. Part of what made her so compelling for Jews of my generation is that we think of Holocaust survivors as these elderly people who come from a different world, and Anne isn’t like that. She’s a teenager like anybody we might have known.

When and how did this interest bloom into a book project to which you’d devote years of research and writing?

As a literary critic, I’m always very interested in the origin stories of books — how they come to be written, edited, produced, made into the objects that we consume.

I think it was in the ‘90s that I started hearing about how Anne’s diary existed in these different versions. It struck me that it was really important to appreciate that Anne had deliberately revised it herself with the intention of publishing it.

As the decades went on, Anne didn’t fade from public view at all. To the contrary, she just seemed to become more and more iconic.

What I wanted to do in the book was to put those two pieces together, to investigate and try to understand her process and her intentions in creating this book, and also what made it so enduring for so many people over the years.

You say you hope to write “alongside Anne rather than over her.” Why?

In part, it was my response to the implicit question of: Why is it useful to write a biography of somebody who has already narrated her life so beautifully and comprehensively?

Part of what I wanted to do was to explain what was going on outside the annex while Anne was in it. I mean that not just literally, although I do that as well, but also giving context to her larger life and to understand all the social and political and historical forces that contributed to what happened to her.

Reading all the discourse around her, the countless works of scholarship, it struck me that so many people use her as a mouthpiece for their own beliefs, regardless of whether we have any information about what she would have thought about these ideas, or in some cases deliberately contradicting her.

I felt that it was so important to give her a voice in this book, to complicate and elaborate on her own narrative without replacing it.

What do you mean when you talk about Anne’s transformation into an icon?

In one way, I mean it literally. Her face appears on billboards, her image is made into memes, her quotes appear on Instagram. She has become this touchstone for all kinds of different things depending on who is using her. She stands for courage. Sometimes she stands for tolerance. She’s a symbol of persecution. It depends who is talking about her.

You looked closely at changes Anne made to her own writing as she revised it for publication, from small details — like changing “If people were told how we Jews lived” to “If we Jews were to tell how we lived” — to larger choices, like removing most of the romance between her and Peter van Pels (sections her father Otto mostly restored). What do these comparisons reveal?

The one you just mentioned, I felt like that was the key to her whole project. That was why she decided to do what she did, essentially. The idea, contained in those little words, that the story of what happened to the Jews of the Netherlands — to the Jews in Europe in general — couldn’t be told by anybody else. It has to be told by them in their own words.

There are changes she made to emphasize the persecution story. Especially early on in the first few months of her diary, when she’s only 13, it makes perfect sense that her first draft is about boys and friends and gossip. When she looks at it again from the perspective of somebody who is not only two years older, but had experienced a lifetime of events in those two years and matured extremely quickly because of that, she realized that if her diary is going to work as a document of persecution, it needed to have a lot more about the actual persecution.

So she went back and she actually wrote new entries with new dates [with] stories she hadn’t included the first time around. She has one about going to the dentist on a very hot day when she has to walk for an hour across the city because, as she points out, Jews are no longer allowed to use public transportation. She points out not only what the new Nazi regulations are, but the effect they have on her as an ordinary person.

She also made changes for the sake of style, to make the diary more readable, more engaging. To make the language more dramatic or emotional. It’s clear that she was thinking about things on an artistic level, as a writer, in addition to on a testimonial level, as a witness.

You talk about several common misconceptions about Anne and the “Diary.” What have we gotten wrong that you’d be most eager to dispel?

I felt frustrated by all the misconceptions and, frankly, misinformation there is about her. As I got deeper and deeper into this work, I couldn’t help noticing these myths. I think the most fraught aspect of her legacy, in some ways, is her father’s editing of the diary.

Reading the “Diary” as an adult and especially as a parent was very different from the experience of reading it as a child. It made me very sympathetic to Otto Frank. As a parent, it’s impossible to imagine oneself in his position. He’s the only member of his family, and the only resident of the eight in the annex, to survive the war. He is given this gift that is also a burden. He immediately saw its potential to reach so many people and, as he said, to work for peace and tolerance. I found it kind of mind boggling that he’s been so vilified by people who think of themselves as Anne’s defenders. People believe that he censored her thoughts about her body, her criticisms of her mother, her bisexuality.

In the book, I trace some of the ways in which I believe these misconceptions came about. I find it sad, actually, that readers have been so eager to jump to conclusions about what he did or didn’t do without checking the sources. In some way, I hope that my book corrects the record.

Can you talk a bit about the unique experiences of women in the camps and what this might tell us about the last months of Anne’s life?

It was important to me to try to reconstruct what happened to Anne first in Westerbork, then in Auschwitz and finally in Bergen-Belsen. There’s testimony from people who knew her in the camps and remember having seen her there. But it’s limited. To fill out that picture, I read as many testimonies as I could find by women who were in the camp at the same time as she was. The women’s accounts differ [from familiar stories by Primo Levi, Elie Wiesel and others] in some details that might seem minor, but actually had a huge impact.

I’ll give one example. We picture the typical prisoner at Auschwitz as wearing the striped uniform. Well, women didn’t wear that striped uniform. They were given ordinary clothes, but without regard for the appropriateness to their circumstances. So you might see women being forced to wear dresses that were revealing, or made out of very light fabric in the cold Polish winter. They might have been given high-heeled shoes they had to walk around the camp in.

I think a more important way, and this has been the subject of some debate by Holocaust historians, but I find the accounts persuasive by historians who’ve argued that women showed a greater amount of cooperation amongst each other. We see this specifically with regard to Anne. A number of the other women prisoners who knew her in the camp talk about how close she was not just to her sister, Margot, but also to her mother. The women in Auschwitz would form these little groups. [They] pooled their resources, their food, their possessions. They tried to provide for each other. This is really striking and something we don’t see nearly as much in the accounts of male prisoners.

And then, of course, the other component is sexual violence. The threat of sexual violence, either on behalf of the guards or fellow prisoners who were in a more powerful position, was one that was always present for these women. To this day, this is an element of the Holocaust that is almost never talked about.

You talk about how “the extraordinary effect of the ‘Diary’ depends on her death.” Can you unpack that a little?

That’s certainly something that has made it so malleable as a text. The fact that Anne isn’t around to tell us what she meant or didn’t mean has made it possible for people to interpret her words in all kinds of different ways. On the one hand, it surely has helped the book be so enduring. On the other, it has made it ripe for misinterpretation.

I think Otto was always, on some level, aware that this was a danger. It’s why he was so anxious about the “Diary” being adapted for Broadway. He realized that was always going to involve a level of fictionalization. Once she becomes a fictional character, anybody can do whatever they want with her.

That’s exactly what we see happening in the works I discuss in which she appears counter-historically as having survived the war. Those books are never about her as a person. She becomes a mirror to reflect the preoccupation of whoever is writing about her.

In the “Pawn” chapter, you write that “no one can know what political beliefs a surviving Anne would have held.” How does her invocation in the name of a vast range of political causes play into how we’ve distanced ourselves from Anne as a person?

This is a problem that presented itself from the moment the “Diary” was published. There is a tension between whether to understand it in a particular way, as a document of the Holocaust, or in a universal way, as a document against persecution more generally. This is made even more complicated by Otto Frank’s desire that it reach the largest possible number of people and be a beacon against intolerance, understood broadly.

Otto realized that had the potential to go in all sorts of directions and tried to walk it back and say that the “Diary” had to be a Jewish book. But by that point, the genie is already out of the bottle and he’s opened the door for all kinds of new interpretations.

We see in the ‘60s, the Anne Frank House hosts an exhibition against apartheid in South Africa, which made Otto Frank uncomfortable with the parallels being drawn. We see her embraced by Japanese culture in a way that seems to elide the role of the Japanese in World War II as allies of the Nazis. And in the present moment, there’s an image of her wearing a keffiyeh that is often circulated by anti-Zionists who seem to be arguing that if Anne were alive today, she would be supporting the Palestinian cause.

My take is that we cannot ascribe any of these positions to Anne, who, during her lifetime, almost never expressed any kind of politics whatsoever. Especially the question of Israel, I think, is very fraught. Western European Jews like her family were not the primary supporters of Zionism before the war. But after the Holocaust, Israel took in the greatest number of survivors who had nowhere else to go. Jews like Otto Frank, who were not Zionists before the war, became supporters of Israel, I would say not only by necessity, but also because they believed in the aftermath of the Holocaust that there was a need for a Jewish state. That is the position that the majority of Holocaust survivors and the majority of American Jews today tend to take. That is why there’s a special provocation in recruiting her for the anti-Zionist cause.

What do we stand to gain by looking closely and seeing Anne as a real person?

A few weeks ago, I was giving a talk to a group of undergraduates. At the end, a male student raises his hand and says, “All this time, you’ve been talking about the relevance of Anne Frank for us today. Why should we assume that she’s relevant? She was just a girl who wrote a diary.”

People for decades have thought that Anne Frank is just a girl who wrote a diary. The critics have literally called her diary a found object that was picked up from the floor of the annex, rather than acknowledging that she created herself as a voice of the Holocaust. That she heard a Dutch minister on the radio call for citizens to preserve their documents of the war years for a future national archive so that people would have a full understanding of what had really happened to them. She heard that as a personal call. And she resolved that her diary was going to be a document that told the story of the Holocaust to the world.

To think that she was just a girl who wrote a diary diminishes her achievement. The idea that she could accidentally write a book that went on to mean so many things to so many people, I think it does her an enormous disservice. We owe it to her to understand who she really was and what she was trying to do.