The place, Smith College. The time, 2021. After two years of inquiries and pestering, I finally succumbed to the desires of my grandmother: I enrolled in a Jewish studies course.

Like many college students working two jobs and participating in more clubs than they have fingers, I found the additional volume of my course readings only added to the noise in my head. The one shred of self-awareness I possessed allowed me to reflect that I’d often been the kind of person that kept myself too busy to think, perhaps to purposefully keep myself out of my own head, and my course readings required I slow down and spend time with my thoughts. But as I dragged myself to a local coffee shop in downtown Northampton on an October afternoon two years ago, I decided that this time I probably ought to do something to prepare myself for tomorrow’s class.

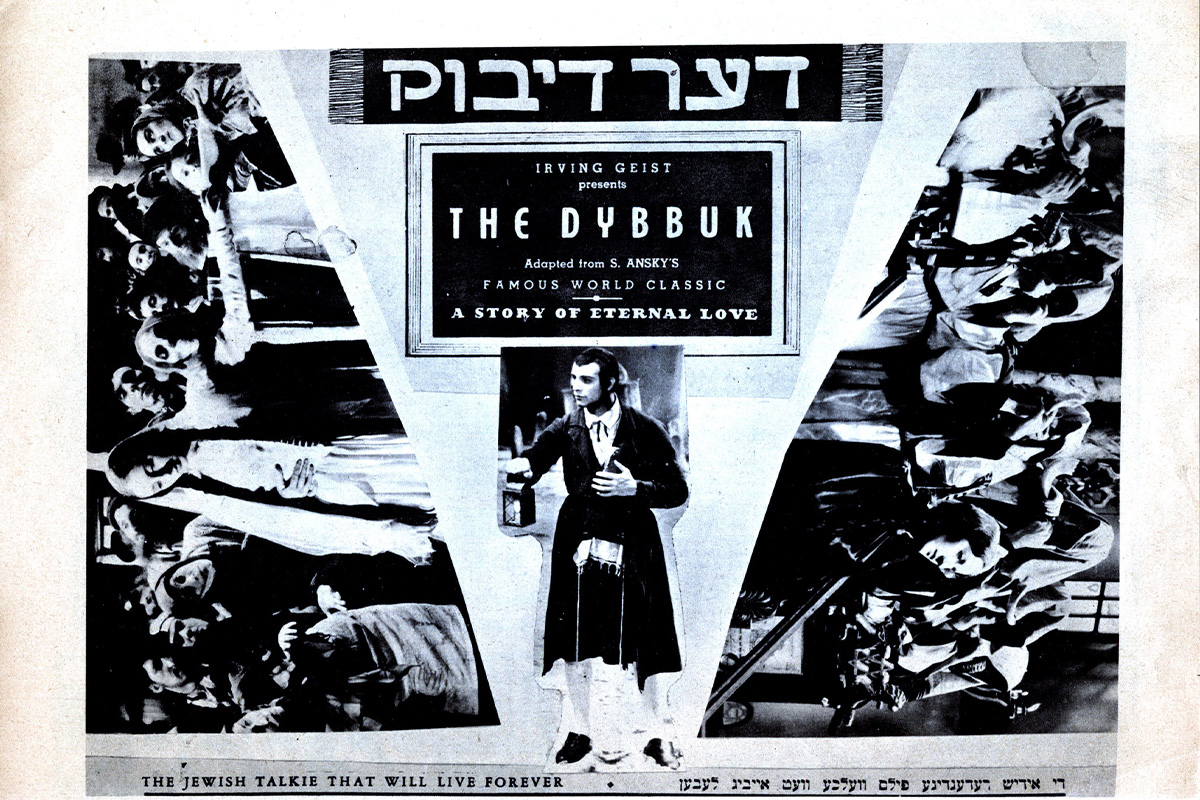

I sat down on the cafe’s hardwood bench, cracked open my copy of “The Dybbuk” translated by Golda Werman and resigned myself to actually doing my homework. But I needn’t have felt so reluctant. In what felt like mere minutes, I’d read every page of Jewish writer S. Ansky’s play. And for the first time in my life I was brought into heightened sentience… by a homework assignment.

“The Dybbuk” is a tragedy that found me during a time of immense grappling. I think many of us feel this way in college, as we try to figure out, well, everything. Questions that ran through my head daily included: What do I believe? How do I understand my place in the world? What kind of person do I want to be? What kind of person can I actually be? How can I give meaningfully? How do I trust that when it comes down to me, I will make the right choice? Do I make my ancestors proud?

That first day I read the play, sitting on the cafe bench in downtown Northampton, all those questions swirling around in my mind, this is the paragraph that stood out to me the most:

“A person is born to live a long life. But if he dies before his time, what happens to his unlived life, his joys and his sorrows, the ideas he did not have time to develop, the deeds he had no chance to do? What happens to the children who were to have been born to him? Where are they? Where?…[W]hen the flame of a candle is snuffed out, you can relight it and it burns to the end. So how can the uncompleted life of a person be stamped out forever? How can it?”

With those words, written in the voice of his character Leah, Ansky reflects on the loss he witnessed throughout his turn-of-the-century ethnographic mission to record the lives and legends of Eastern European Jewry. Though Ansky wrote the play between the years 1912 and 1917, Leah’s words resonated deeply for me in 2021. Today they resonate still, as my now worn copy of “The Dybbuk” has seen me through startling growth, challenge and joy.

“The Dybbuk” tells the story of a young woman, Leah, her love Khonon, their respective family histories and the journey of a mysterious messenger. In short, the couple are kept from a happy marriage by class division and the will of Leah’s father. As Leah’s betrothal to another man swiftly approaches, Khonon turns to Kabbalah, also commonly referred to as Jewish mysticism, to stop the wedding and receive his rightful happy ending with the woman he loves. Unfortunately, his spells and week-long fasts do nothing but lead to his ultimate demise. After several broken engagements, when a successful match for Leah is proudly announced by her father in the synagogue, Khonon drops dead, stricken with grief.

Surprised by the effect his death has on her, Leah questions what it means to lose someone she doesn’t want to be without, and yet hardly knows. While enjoying time with her grandmother and other women of her family before the wedding, Leah speaks of the comfort spirits offer her, including Khonon’s. The spirits are not evil, she says, but warm and familiar. She asks her grandmother if when she goes to the cemetery to invite the souls of her family past, if she too can invite Khonon to the wedding. Her grandmother is not pleased, but agrees that it will be fine if Leah will just cheer up and stop asking bothersome questions.

Under the chuppah, right before Leah can be wed to her father’s chosen groom, the spirit of Khonon possesses her. He is a spirit with unfinished business, which prevents him from passing to the next world: a dybbuk. The wedding cannot continue and Leah’s family is horrified, naturally.

In order to resolve the issue a rabbinic trial is called to put the living and the dead in conversation with one another. With rabbinical judges presiding, the audience learns, just as the characters do, that Khonon and Leah were always meant to be together. If Leah’s father had only opened his eyes, he could have seen that Khonon was the son of his best friend — his best friend he had made a promise to decades prior. The promise: If one man was to have a boy and the other a girl then the two children would be married, joining the two families in harmony. Tragically, the memory of this promise died with Khonon’s father. As the years drifted by and Leah’s father never heard from his dear friend, or of the existence of a surviving son, he forgot and moved on.

Now back to the wedding. The lovers find themselves stuck between two worlds, this one and the next, and it is up to Leah to decide which world she will choose.

The curtain closes as she joins Khonon in the afterlife.

When reading “The Dybbuk,” one may take the traditional boy gets girl, boy loses girl, boy possesses girl, girl joins boy in the next world progression at face value. But like any good story I’ve ever been told by a Jewish person, within the larger arch of this play is a seemingly unrelated and curiously embedded tale. Throughout the first portion of the 20th century, during which Ansky wrote his final play, many Jews fell, never to rise again. “The Dybbuk” then, by deeply exploring Jewish grief, implores the Jewish people, in the context of unimaginable loss and destruction, to re-imagine their collective history for an evolving modern context. And by centering Leah in this uniquely Jewish loss, Ansky centers the voice of Jewish women in his call for collective cultural re-imagining.

As Leah is told and re-tells the same tragic Jewish folk stories and legends, she is destined to meet the same fate of the figures in those stories, that of an untimely death and unfinished life. A tree cutdown just as it is beginning to blossom, or a candle snuffed out before it burns to the end, should not be remembered or glorified as symbols of grief alone. Rather they should serve as reminders to resist letting those tragedies happen in the first place. This is what Ansky teaches us. In the face of grief, collective cultural relics can be more than just relics, they can be vital inflection points.

As “The Dybbuk” and my time with Leah came to an end, I was met with nothing but the words on the page to comfort me. I felt no choice but to look beyond them for something more. Just like Leah, I wasn’t satisfied with the ending that had been put before me. A passive Jewish woman, standing still, letting life pass her by, won’t change a thing nor will she discover her power to do so. Time is a precious resource: each breath, conversation, lesson, opportunity to do better next time, a gift.

On that sunny October afternoon, Leah became a mirror through which I am still able to see myself. No woman is perfect, nor should she be. And put in Leah’s shoes who knows what I’d do. Leah asserted her agency as a Jewish woman in her time, in her way, choosing a fantastical love that transcended the limits of our world. Her story to me is like the sound of the shofar, calling me to be present in my feelings, examine truths more closely and beautifully grieve my missteps, especially those which are worn hard into the earth. Leah calls me to remember who I come from, where I come from and who I am. She is a reminder to actively answer my questions, keep searching and move forward.

Though our current moment can feel aimless, out of control and more keenly, out of our hands, Ansky reminds us that it is not. There is more to every story than meets the eye. I am grappling still, but comforted by the rich tradition of Jewish storytelling and how it has challenged me to slow down, quiet the noise, and think deeply. In true Jewish fashion, “The Dybbuk” continues to leave me with more questions than answers. But it is in the asking that redemptive seeds find their light.

Late Take is a series on Hey Alma where we revisit Jewish pop culture of the past for no reason, other than the fact that we can’t stop thinking about it?? If you have a pitch for this column, please e-mail submissions@heyalma.com with “Late Take” in the subject line.