The world as we knew it changed in 2020. While we all stayed home to stop the spread of COVID-19, West Coast wildfires threatened the home of Jewish artist Isaac Brynjegard-Bialik and people across America gathered to state that “Black lives matter.” Brynjegard-Bialik started looking for a way to cope with the emotional toll of all of the above.

The Southern California-based artist started cutting up comic books to craft golems, the Jewish mythological creatures made from earthly materials and brought to life by their human creators. This marriage between Judaism and hand-drawn tales of justice came naturally to Brynjegard-Bialik, a super-fan of superheroes who keeps a Green Lantern ring at his desk.

Brynjegard-Bialik began making golems as a way to regain a sense of control over his life. His anthropomorphic creatures are designed to protect, defend, inspire and amuse. They contain the images of many beloved comic book heroes, including Superman and Wonder Woman.

Some of Brynjegard-Bialik’s colorful creatures feature the traditional golem forehead inscription “emet,” meaning truth. Others, he inscribed with comic book captions that give the golems different powers — usually whatever Brynjegard-Bialik felt he needed at the time. As the pandemic continued, so did his work on golems: Brynjegard-Bialik eventually crafted 72. Now, the UCLA Hillel is displaying all 72 in an exhibit called “Paper Golems: A Pandemic Diary.”

In addition to his art, Brynjegard-Bialik and his wife, Rabbi Shawna Brynjegard-Bialik, created Paper Midrash. Before COVID, they traveled around the country doing artist-and-rabbi-in-residence weekends, bringing together pop culture, comic books, art and scholarship in pop culture sermons, hands-on workshops and other programs. They pivoted during the pandemic and now do online “Make Your Own Golem” workshops.

I spoke to Brynjegard-Bialik about managing anxiety with art, what it’s like cutting up vintage comic books and learned all about his favorite superheroes.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

When did golems become an important part of your life and art?

Golems didn’t play a role in my life until the pandemic hit. That’s when I started thinking about the golem story as something relevant for me to explore, since I started feeling very nervous all the time. When those lockdowns started, we started seeing a lot of parallels to science fiction, end-of-the-world-type storylines. I started to really feel that pressure and stress and anxiety, as everyone did. Normally, when I’m feeling off or when I need a pick-me-up, I cut paper. I make art.

They’re very personal responses to whatever happened to be going on: whatever I was trying to process, what’s bothering me and what I need more of. They’re a representation of how we can protect ourselves, anda way to think about what I can do to feel safe. In my case, that’s making golems out of comic books.

Golems have been a part of our stories for so long. I thought, maybe there’s something to this. Maybe there’s a reason that artists keep drawing them, writers keep writing about them and sculptors keep making figures of them. I thought something about … the artistic endeavor of making one might bring me some comfort. It sort of spiraled out of control, as golems do. I made one, and it just really made sense to me. And then I made another, and all of a sudden I have 72 of them.

Will you take me through your process of making a golem? How do you come up with what it’s going to look like? How do you pick the colors, the comics, the shape? I’d especially love to know how you came up with my personal favorite, No.6. I love this golem’s red wings.

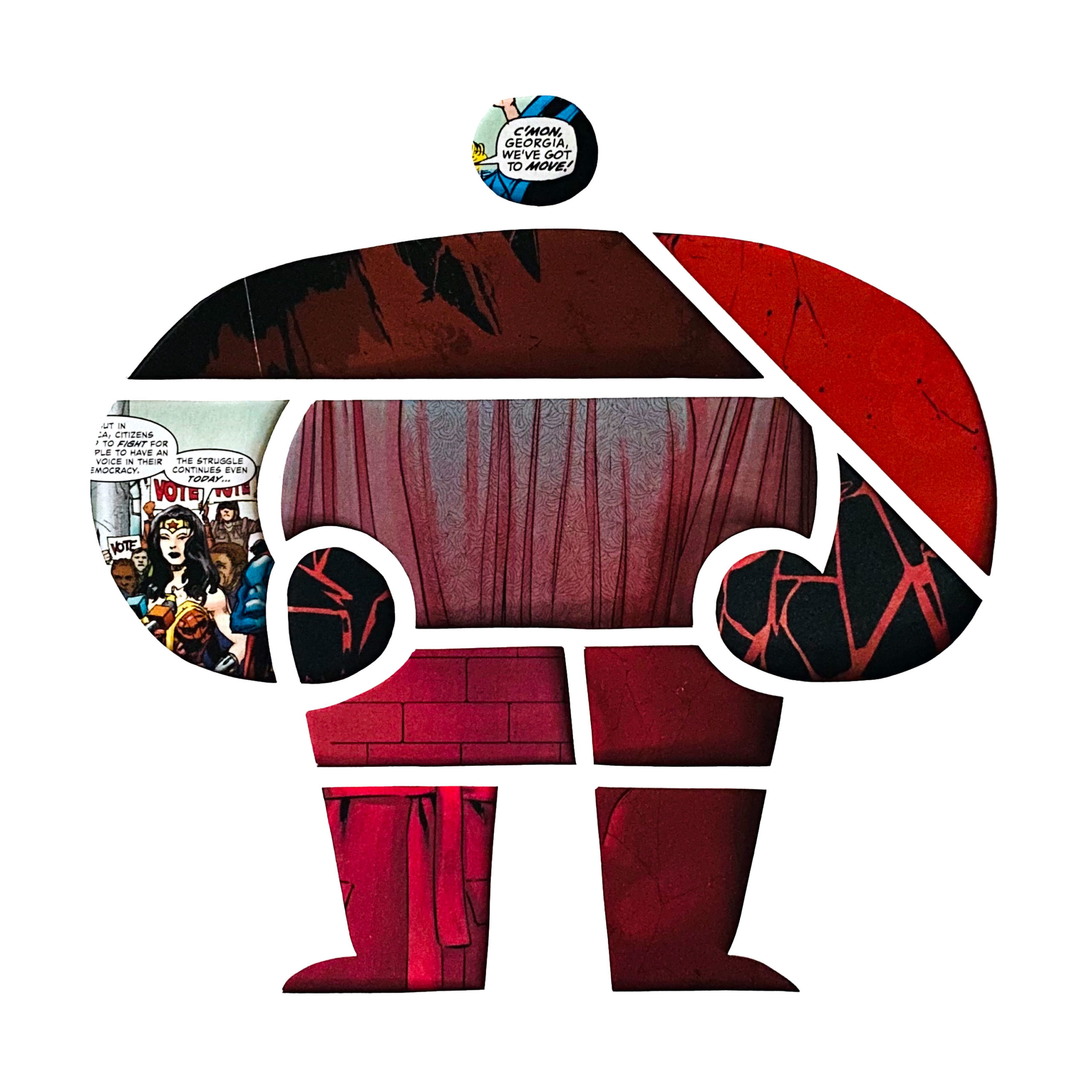

[No.6] is called “Truth and Justice.” It’s made out of Superman comics. I wanted to sort of translate that idea of flight. I was thinking of the Shekhinah — God’s sheltering, feminine presence — and how we talk about the metaphorical wings. Since superhero comics are already a metaphor for everything, why not? So, I turned Superman into this winged golem.

I like the idea that truth and justice are these sheltering concepts. This one was early on in the series when I was still playing with the ideas of protection, safety and truth… With all of them, I started thinking, what is the thing I need right now? As I said, these were a pandemic diary. The golems are different from the rest of my work in that I would wake up and say, “You know what? I’m feeling sort of anxious about the fires that are two miles north of here and are spreading unchecked. Well, what hero do I need today?” And so the golem that I made, No. 20, “Fireman,” was made with Aquaman comics, because I needed water that day.

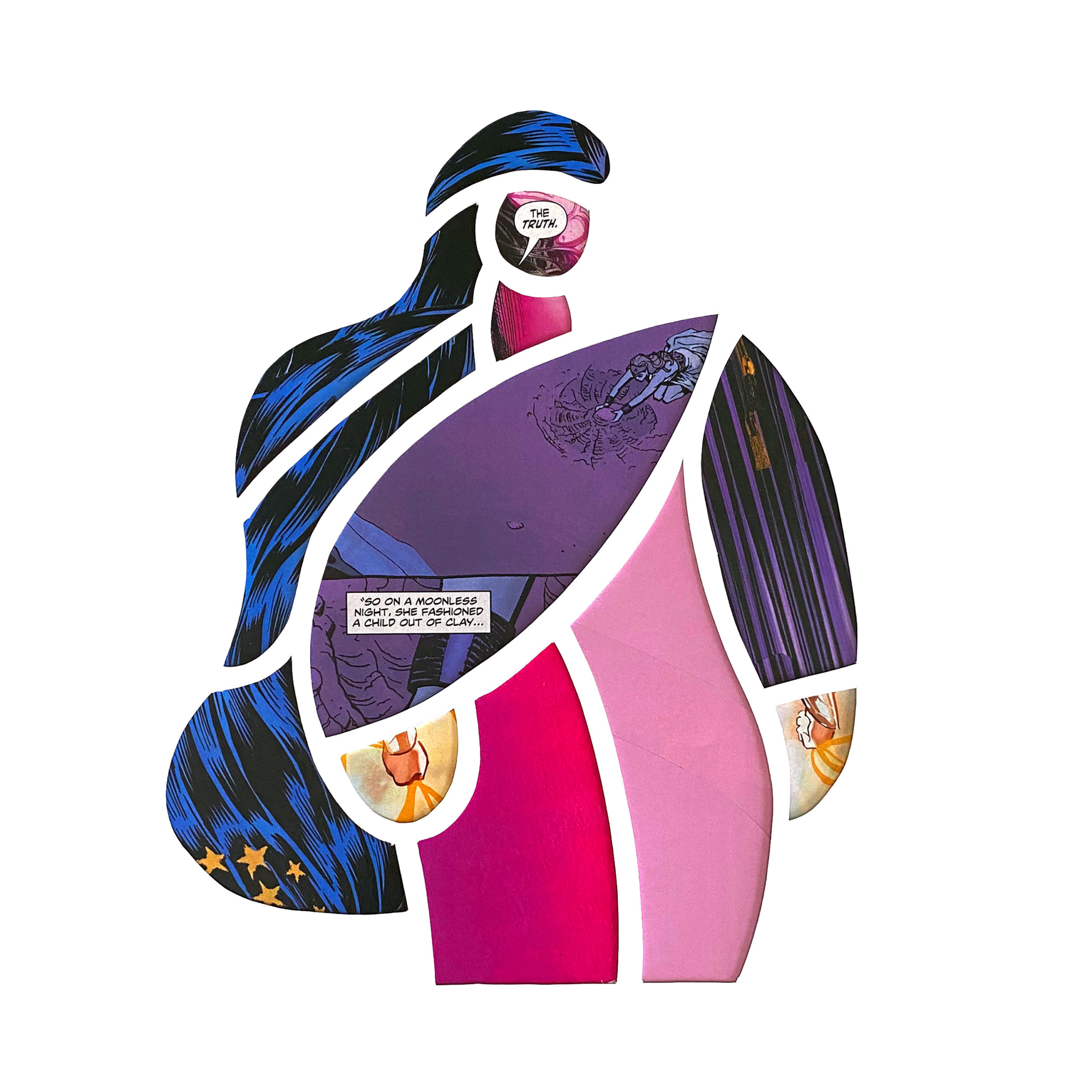

There’s a golem I called “Fury.” In it, you can see people protesting and holding signs. You can see a lot of anger, you can see a lot of lightning, which is this analog to that anger. There were days we were looking at these protests in the streets and when everyone was really understanding what it meant to say “Black lives matter.” The idea that one person holding a sign or writing a letter may seem like they can’t get anything done, but when you get enough people together, that positive change can be affected.

Everybody has their to be the hero, be the golem that we need. It’s not about making a golem and letting it do its job. It’s about being strong ourselves so we can protect ourselves and each other.

How does it feel to cut up comics? It seems like it’s something so personal for you, but also necessary to the craft. When you cut them up are you just like, “I’ve got to do this!” Or is it a little heartbreaking for you?

The first time I realized I wanted to play around with comics in my paper cutting, I was in the studio. I was looking at the comics behind a cut-out and I thought, “This is something interesting.” I didn’t want to cut up my own comics because that would have been crazy. I went to a comic shop, and I bought one of those 20 packs of comics for $20. I thought, okay, I don’t have any emotional attachment to these. They’re just throwaways, and I can cut them up. There was something about the textures and the paper and the ink and the smell of them.

It was hard to cut up my own comics. There are some in my collection that I will probably never put the knife to, but I’ve cut up signed comics. I’ve cut up what would probably be considered collectors’ issues, old comics and new comics. There’s something about using the comics that I bought and read as a kid and even ones that I buy now to read. They become a part of my story. I feel like there’s something really special about using the comics that I’ve enjoyed and remixing them or recontextualizing them in these Jewish stories.

I now realize that is what I was saving them for. You wonder, “Why do you have all these comics?” I mean, they’re not an investment. That was clear. I was apparently saving it to make my art.

Your artwork is so vibrant, and when I look at your golems, I feel their strength. What is it like for you as an artist to create such a strong, colorful depiction of such an ancient Jewish thing? How do you think any non-Jews who aren’t familiar with golems will perceive it?

I think that we’re used to seeing Jewish ideas in our pop culture vernacular, not just because Jews were instrumental in starting the comic book industry and the modern film industry, but also because Jews are storytellers at heart.

I think the golem story is one that anyone can connect to, even though it has Jewish origins. In the same way… my golems are so very personal, but I think people get the universality of them.

I’d love to hear who your favorite superheroes are.

I’ve got plenty of favorite superheroes. I think it’s often said that every generation has the Batman they need, and Batman changes depending on the audience. I think that’s the case with all of us and our heroes. I’ve always loved Green Lantern since I was a kid. I love the idea that he has a ring — in fact, do I have one right here? — I’ve got my Green Lantern ring right here.

No way! That’s so cool.

I love the idea that this ring enables me to turn whatever I can imagine into reality. Reality can be used to defend people. Green Lantern has always done that, no matter who wears the ring. I love that idea. And of course, it ties into the Theodor Herzl thing, if you will: “It is no dream.” I love that maybe there’s this accidental connection to our Zionist ideas within Judaism.

That said, I have a real soft spot in my heart for the Jewish heroes. Heroes like Kitty Pryde. I discovered the X-Men at a time when Kitty Pryde had just been introduced as this 14-year-old girl from Chicago who discovers that she has mutant abilities. She shows up in these X-Men comics wearing a Jewish star. And she has been wearing that Jewish star for the past… I guess it’s 40 years now. In every incarnation, every artist knows that’s the way you show her visually and every writer knows that her Judaism is a part of her story. It’s a part of why she’s a hero.

The Dortort Center for the Arts Gallery at UCLA Hillel displays all 72 of Brynjegard-Bialik’s golems from Jan. 27 through March 11, 2022.