Clementine began her existence as a video game character, in Telltale Games’ landmark Walking Dead series, back in 2012. There, she was an 8-year-old kid we met in Atlanta just as a zombie apocalypse chugs into motion. As sometimes happens in popular culture, Clementine’s story curiously resembled that of a character in another fictional property released at almost the exact same time: The Last of Us (TLOU), which appeared first as a video game on PlayStation 3 in 2013, and more recently as a series adapted for HBO.

Like Ellie in TLOU, Clementine contends with zombies who are never called zombies (instead Ellie has “infected” and Clem has “walkers”). Like Ellie, she connects with a morally compromised surrogate father to whom she serves as a moral compass (Ellie:Joel::Clem:Lee), travels across several U.S. cities to get to a safer place, loses friends and learns to fire a gun for self-protection. Both characters appear across media forms, too: Ellie, a comic book fan herself, also appeared in a spinoff 2013 comic called “American Dreams” drawn by Faith Erin Hicks, and now Clementine headlines a comic series written and drawn by the wonderful Tillie Walden.

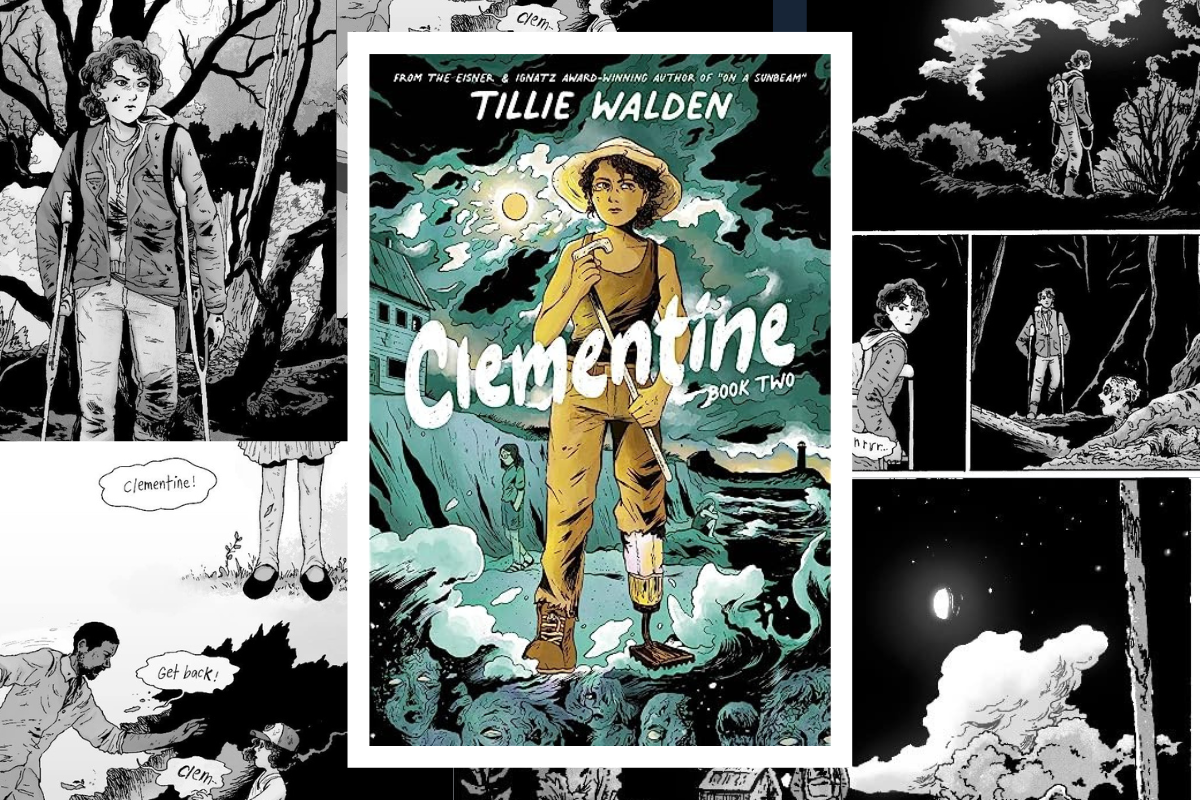

If you track Ellie’s and Clementine’s stories up to the present — in The Last of Us, Part 2, which came out a few years ago and is currently being adapted for HBO, and in Walden’s newest comic, “Clementine: Book Two,” which is being published on October 3 — you find that these two teenagers have something else in common, something somewhat less predictable from the generic conventions of zombie media.

They both have Sephardic girlfriends.

A good bit of enthusiastic ink has already been spilled about Ellie’s girlfriend Dina, but I don’t think as many people have noticed Ricca, who is easily one of Walden’s most compelling contributions to the Walking Deaduniverse. Early in “Clementine: Book One,” Ricca wonders if she’s “the last Sephardic Jew left” (and I am patriotically required to mention that she’s Canadian, too). But we don’t see what that identification means to her until the very end of the book, when she very slightly mispronounces the beginning of Tefilat Haderech, the traveler’s prayer, as she and her friends take off in a small airplane that is miraculously still functioning after the apocalypse.

In “Clementine: Book Two,” the girls’ adventures continue, and Ricca repeatedly turns to Jewish songs and rituals for strength, even as she can barely remember the Judaism she practiced with her family before the zombies started to attack. (Please skip the next two paragraphs if you don’t want story spoilers for “Clementine: Book Two.”)

At one point, to comfort an injured Clementine, she sings what she can remember of the Friday night classic “Shalom Aleichem,” and then when they find themselves in a relatively safe community, Ricca turns to building herself a makeshift synagogue.

Ricca, Clem and another of their friends understand that they’re children who have had to grow up way too fast, because zombies — so Ricca leads them through what she can remember of the ritual of bat mitzvah. “I’m pretty sure you recite some stuff from the Torah to start,” she says, “then talk about what you learned.” It’s a touching, sensitively handled scene that helps the emotionally defended Clem get to a place where she can finally tell Ricca she loves her. After that, Ricca and Clem have sex for the first time, and so it’s pretty clear that Walden wanted the focus of “Book Two” to be on Clementine belatedly becoming an adult, whatever that means in her astonishingly shitty world. (Is there anything more perfectly YA than that?) While the setting and circumstances remain extremely grim, and notwithstanding heaps of zombie-murder and all the people being ripped limb from limb, you can still feel Walden’s gentleness and kindness to her characters.

In her brilliant, award-winning 2017 memoir, “Spinning,” Walden touched briefly on how strange it felt for her to be a Jewish kid in the very Christian world of competitive figure skating in Texas, but to my knowledge this sequence with Ricca is the most substantial, complex invocation of Jewishness in Walden’s oeuvre to date. (I don’t recall spotting any Jewish characters in the gorgeous 2018 space fantasy “On a Sunbeam” or Walden’s phantasmagoric road trip book, “Are You Listening?”)

Walden is easily one of the most talented comics artists of our moment; two of her books have won Eisner awards, which are like the Oscars for comics (and named for Will Eisner, the Jewish comics pioneer), and she teaches at the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont. Thoughtful attention to just how diverse people can be is one consistent feature across all of Walden’s books, and it’s lovely to see, in “Clementine: Book Two” that a Jewish ritual is something Ricca’s able to share with two characters from different backgrounds. Given the deftness and care with which Walden included them here, we can look forward to whatever she might do with Jewish rituals and culture as this series continues — let’s pray Ricca survives at least a while longer — and in whatever projects she works on in the future.

Meanwhile, as we get adjusted to life in the year 5784, and knowing all the real-world threats to LGBTQ+ teenagers, Jewish or not, that continue to proliferate in the U.S. and around the world, I hope we can take some small amount of solace in a consensus that seems to be developing among the authors of speculative fiction that when the zombie apocalypse arrives, there will still be opportunities for queer Sephardic teenagers to find their soulmates.