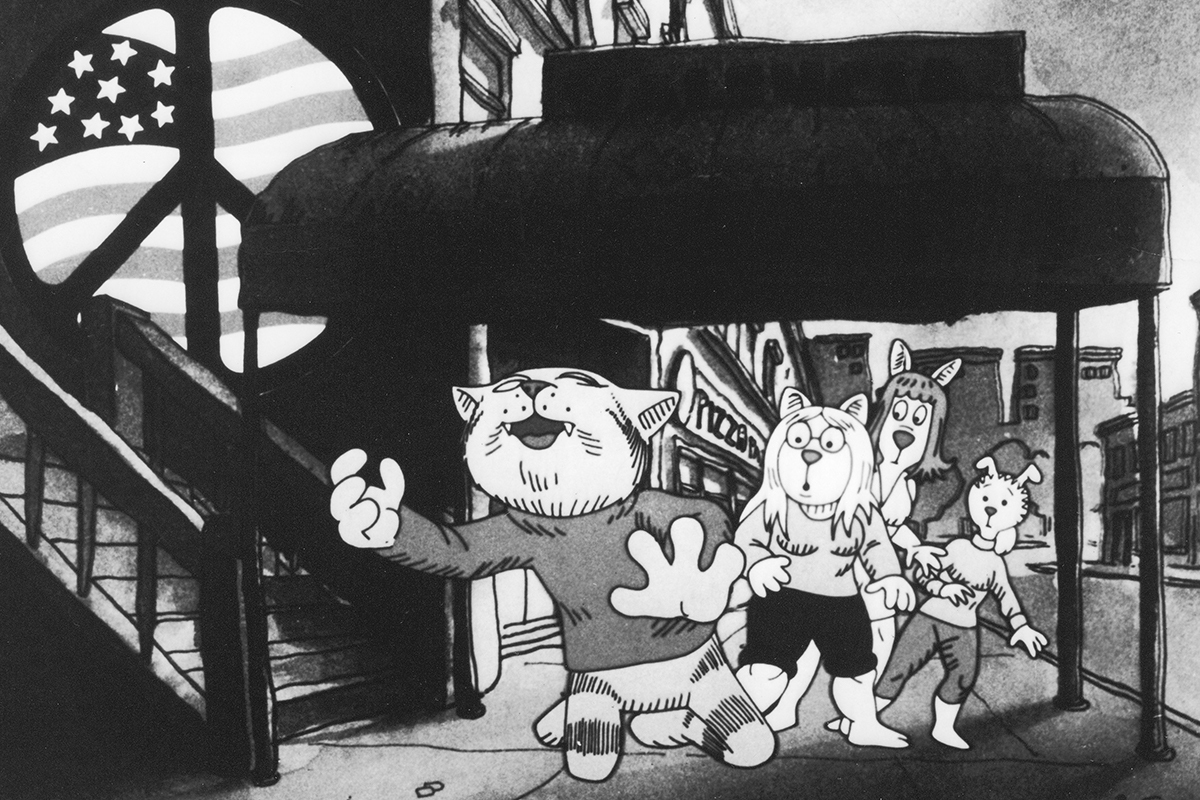

Far from the wealthy Californian neighborhoods of Curb Your Enthusiasm and the Jewish Westchester of Netflix’s Big Mouth is animator Ralph Bakshi’s Jewish New York. It’s a strange and gritty world that the little-known Jewish animator crafted for himself over the course of a handful movies he directed through the 1970s and 1980s: Fritz the Cat, American Pop, and his magnum opus, Heavy Traffic.

Despite the fact that these movies were produced more than 40 years ago, they remain a meaningful addition to the world of Jewish American media.

Around 17, I first discovered Bakshi’s films. From the first few scenes of Heavy Traffic, I recognized something that was deeply Jewish and yet completely unparalleled in other Jewish cultural production. I became endlessly intrigued; I started watching YouTube documentaries, reading online articles, and looking for any piece of writing on the animator. The sheer bizarreness of Bashki’s movies had barred them from mainstream success yet spurred in me an interest in their creator. In trying to understand Bakshi’s movies, it became crucial to me to understand his background and the way he saw the world.

Ralph Bakshi grew up as an outsider to American Ashkenazim. He was born in Haifa in 1938 to a Krymchak Jewish family, a little known Jewish ethnic group that lived among Turkik Tatars and is distinct from other Jewish communities of Europe. His family moved to the U.S. in 1939 and settled first in Brooklyn and later D.C.

Bakshi grew up poor in majority Black neighborhoods in these cities and, though he was not a Black student, even attended an all-Black school in Washington before being forced to leave. The animator likely would have found the culture of Mrs. Maisel-type Ashkenazi Judaism — upper class and homogenous — totally alien. In his work, he sometimes even took aim at mainstream American Judaism. For example, in Fritz the Cat, an assumedly suburban and assimilated Jewish girl proudly proclaims that “Jewish people are the closest to Black people,” to which other characters roll their eyes.

Bakshi’s work appears like an animated Martin Scorsese fever dream. Scenes throughout his movies are bizarre; they mix styles of art, lapsing into song and live action at times. Plots in his films range from the story of an intergenerational family of musicians in American Pop to chronicling the misadventures of a 22-year-old virgin cartoonist in Heavy Traffic. At times, the movies are strange past the point of enjoyment and I am left rolling my eyes at scenes that seem to shock for the sake of shock.

Yet throughout Bakshi’s oeuvre, there emerges a fundamentally Jewish world, as alien as it may be to middle class Jewish suburbia. In American Pop, the family patriarch, Zalmie, emigrates from the old country to New York City. Heavy Traffic’s protagonist, Micheal, is Jewish and Italian, and both sides of his family play a major role in the movie. Bakshi positions many of his Jewish characters as atypical of American Jews; Micheal’s Italian background, for example, and American Pop’s focus on assimilated and unassimilated immigrant Jews alike. His Jewish characters frequently are in relationships with non-Jews, something still somewhat taboo at the time of his films’ releases. And few of Bakshi’s characters — and none of his protagonists — are practicing Jews.

Bakshi’s focus on ethnicity struck me in particular. His refusal to busy himself with any kind of post-racial utopia building deeply resonated with me. I am someone who, despite growing up in an ethnically diverse place, has rarely seen anything close to a “post-racial” society. Ethnic and racial division, voluntary or not, are self-evident throughout his movies.

In Bakshi’s work, this kind of diversity becomes the marker of a distinctly working class Jewish existence. His world is populated with Italian greasers, immigrants, and a whole cast of characters borrowed from the Blaxploitation films of the same era. For every rabbi included in his movies, Bakshi includes a character type uncommon elsewhere in the American Jewish canon: sex workers, cult members, mobsters, and more. In many ways, this leads to choices on Bakshi’s part that may have served as racial commentary, albeit a lazy one, decades ago, but have now aged to reflect nothing more than ignorance and insensitivity. At other times, this strange diversity leads to thoughtful moments, such as the police murder of Duke, a Black character in Fritz the Cat, which is drawn out in a painful and reflective manner.

Bakshi had a complicated relationship with race. From his background, it is clear that he was aware of the cruelty of segregation and American racism. Indeed, he made efforts to include Black creatives in his world, like the animator Brenda Banks and musician and actor Barry White. Many of his films are distinctly anti-racist, commenting on police brutality and making frequent references to how the promises of America often ring false for Black communities.

Yet, many of his films have elements that, viewed in 2020, come off as blatantly racist. In attempts at artistic edginess, Bakshi sometimes uses imagery associated with minstrel shows. Racial slurs likewise are commonplace in Bakshi’s films, referring to both Jewish and Black characters. To me, this seems like a failed attempt at “edginess” and a misguided desire to leave a mark on the American racial imagination. In this way, Bakshi can serve as something of a cautionary tale for those Jews who think they “get it,” an attitude he himself critiqued in Fritz the Cat.

Despite its faults and oddities, the working class Jewish world of Bakshi’s universe resonated with me in some ways that more typical Jewish American media still does not. I grew up in an ethnically diverse and economically diverse neighborhood in New York, where I was more likely to run into washed-up punk musicians and Caribbean immigrants than I was cantors or existential Woody Allen-esque writers. I went to schools that were anything but white and middle class, hanging out after school with the sons and daughters of immigrants from places as diverse as Azerbaijan, India, Eastern Europe, and South America. My family is multiracial, with a brown father and a white mother. I grew up in a working class housing development. My closest friends had experiences that shaped the way I came to see the world.

And while I am middle class, my experiences with wealthier or suburban Jews can leave me feeling a bit estranged. I see the kind of resentment I sometimes harbored for that cultural sphere reflected in Bakshi’s tone.

Bakshi’s work is definitely not for everyone. There’s no doubt his movies have aged poorly, in terms of social messaging and just general quality. Yet, in painting a Jewish world in opposition to the middle class and suburban Jewish life that is hegemonic in Jewish American pop culture, Bakshi captured something worth watching — something at least vaguely akin to real experiences for American Jews like myself, and Jews who might be more familiar with Brighton Beach than Westchester.

Our reality is one that is largely multi-ethnic, urban, and working class — themes Bakshi directly engages with. While these movies definitely don’t present anything close to the reality of most Jews, neither does Curb Your Enthusiasm. In disrupting a solely middle class narrative of Jewish identity in America, Bakshi does something important: He reminds us of the complexities of Jewish existence in the American experiment.

Complete versions of Bakshi’s movies are easily available on Youtube.