It’s an understatement to say that the Holocaust was a historical event that continues to impact our world today. From the various memorial days such as Yom HaShoah, to fighting anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that deny the Holocaust, to the stories of many of our families, the Holocaust comes up in a multitude of contexts.

Yet when it comes to telling the stories of those persecuted, it’s the story of one girl that we continue to tell and retell: Anne Frank. Born in Frankfurt, Germany to a Jewish family, Anne Frank fled to the Netherlands in 1934. The family went into hiding in 1942 in Amsterdam, living in an attic known as “The Annex.” Discovered in 1944, the family, and those hiding with them, was sent to concentration camps. Anne, her sister, and her mother perished. Only her father Otto survived.

Anne Frank’s experience is important. And being able to read what she wrote in her diary — an eyewitness account of the persecution of Jews from the lens of what should have been a normal teenage girl — is a blessing. Yet Anne’s is not the only story of someone who died or survived the Holocaust.

Why, then, is it Anne’s story that continually gets retold in the media and books and by Holocaust memorial organizations? From the vlog series released by the Anne Frank House this past May, to multiple picture books about her, to the new “Frank Family Center” at the Jewish Museum of Frankfurt, to a film called #Anne Frank – Parallel Stories now streaming on Netflix, Anne’s story has become the singular Holocaust story for many.

The Holocaust was not one experience. When we place one narrative above the others, we dishonor both the stories of those killed as well as those who survived. It’s the diversity of individual stories that teaches us of both the complexity and depth of the Holocaust and the systemic persecution of Jews living in Europe (as well as parts of Northern Africa).

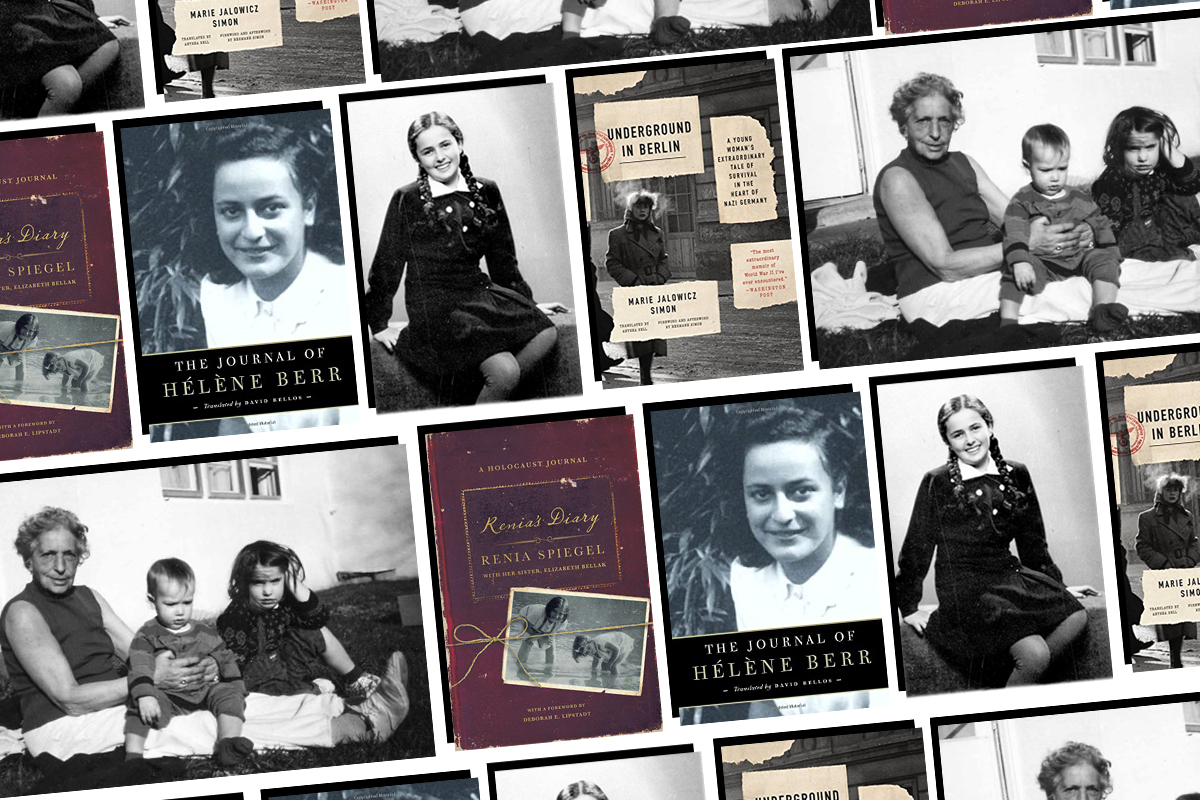

Below are the experiences of five women whose lives were directly impacted by the Holocaust, and whose stories are now readily available to read or listen to. May their — and Anne’s — memories continue to be for a blessing.

Renia Spiegel: Renata “Renia” Spiegel grew up in Poland. She was 15 when the Nazis and the Soviets divided the country in 1939; Renia was stuck with her sister and grandparents on the Soviet side while her mother was in Warsaw, then occupied by the Germans. In her diary, she wrote of the experiences that define the teenage years — including a first love — as well as the horrors of the war. Renia’s former boyfriend Zygmunt brought the diary to her surviving family in New York in the ‘50s. It remained in storage until her great-niece finally sought to have it translated. Only published in English in 2019, Renia’s Diary is a visceral story of the experiences of a young woman who sought to live as the world ultimately closed in around her.

Hana Dubova: Hana Dubova was born in Czechoslovakia in 1925 and spent much of her young life in Prague. Hana left in 1939, beginning a journey that would take her across a Europe marked by war and eventually to the United States. Her granddaughter Rachael Cerrotti tells the story of her survivor grandmother in the podcast series We Share the Same Sky. If you’re looking for something to listen to rather than read, this is a place to begin. And, for those craving something to read, a book is forthcoming in fall 2021.

Marie Jalowicz Simon: Marie Jalowicz was an 11-year-old resident of Berlin when the Nazis came to power in 1933. She was one of the 163,000 Jews living there. As the war picked up, and Berlin Jews were deported from the city, Marie assumed a false identity and began to live illegally in hiding. She became known as a “U-Boat” — a term given to the 7,000 Jews who lived underground. Marie told her story some 50 years after the war ended, telling her tale of survival in her book, Underground in Berlin: A Young Woman’s Extraordinary Tale of Survival in the Heart of Nazi Germany.

Hélène Berr: Hélène Berr was a graduate student at the Sorbonne when she began to keep a diary of her life in 1942. Germany had already occupied France for two years and for the next two years, Hélène wrote of the deteriorating situation of her family and friends as Nazi policies increased. Her diary is that of a young woman caught between university life and World War II. Hélène and her family were sent to the camps in 1944, and Hélène died in Bergen-Belsen in 1945. She left her writings to her fiancé. Years later, her niece sought to get the diary published, which became The Journal of Hélène Berr.

Éva Heyman: Éva Heyman was 13 when German forces occupied Hungary in 1944. She lived with her family in Nagyvárad, a large city in Eastern Hungry. Éva kept her diary for about five months in the spring of 1944. Topics ranged from the mundane, like birthday gifts, to her best friend being killed by the Nazis, having been deported from Hungary several years prior. The Diary of Éva Heyman is a glimpse into how a child understood the perils of the world around them. In addition, her story was the basis for Eva’s Stories, an Instagram project started in 2019 that retold Eva’s story via social media.

Header image design by Emily Burack.