All my life I have been called a Babylonian Jew. I never even thought to question this identity, proudly announcing it to others. I also grew up calling myself an Iraqi Iranian. My grandparents were both born in Iraq and my mother was born in Iran, but I have never been able to visit Iraq or Iran. While I grew up accepting my confusing identity, as I got older I knew I would need to understand what my identity meant for me and for future generations of Jews affected by the diaspora.

Growing up, I also had yet another identity: dancer. I learned how to dance in the Persian and Arabic way to music both in Farsi and Arabic. I was the center of attention at all events that involved (and did not involve) dancing; I was that little girl standing up on the table belly dancing while all of my grandparents and their friends snapped their fingers together in the Arabic way and sang out “Kilililililil.” I learned to dance this way through my parents and grandparents, who were happy to pass down these traditions to me. I could feel their pride as I moved in their old ways: ways that seemed almost gone to them, memories of places they could never return to.

My grandparents grew up in Iraq and were forced to leave in the late 1950s due to an enormous rise of antisemitism. My mother grew up in Tehran and was forced to leave with her family in the late 1970s. She remembers Iran as a magical haven that guards her childhood. Iran was developing and modernizing when an Islamic extremist revolution erupted, endangering the Jewish community. Once again, my grandparents, and now their children, brought what little they could and moved to New York. My mother’s generation carried a heavy burden — this generation had to quickly let go of their life as they knew it, as well as console and support their parents who were older and less able to assimilate to a new culture.

I took on my family’s hardships emotionally and became lost in the memories and the transmission of trauma, digging into history for answers rather than remaining present. For so much of my life I felt tasked with holding my family’s loss of their countries, their cultures, their communities and their childhoods. When I was a child, I wanted to be Iran for my mother. I wanted to bring her the beauty, the love, the sense of paradise and her lost childhood in Iran through my youth, my Iraqi Iranian blood, through my olive skin, my almond shaped eyes, my Middle Eastern brows — I wanted to be the living incarnation of all that she had lost in order to heal with her and to bring her peace.

But I never could replace what she lost — I could not complete the task of solving her trauma. I could not, just in existing, or even in remembering our family history, bring back what was gone. This grew frustrating and painful to be unable to heal the true pain unfolding and to feel somehow attached and connected to that pain, too, even though it has never been my pain to hold.

So when I felt lost, when I felt frustrated, I turned to dance, to my physical body, to the present moment.

In college, I felt even more unsettled in my identity than I had as a child. I started to take improvisational and modern dance classes and found that I could express these feelings about my identity and my family history that felt almost un-expressible, so freely and simply. I began creating a dance with other first generation Americans about identity, family and culture.

But then I felt the dance piece getting away from me. I had been over-intellectualizing it. I decided to go to the dance studio alone and to just move. I closed my eyes and began to dance. I thought about my mom, about my grandparents, Baba Nadji and Mama Lil. I saw them packing and moving and changing their lives like they had told me they had, but it was blurry in my mind. I couldn’t see anything at all if I didn’t stop to close my eyes. I felt myself moving quickly and with ease, like I needed to go somewhere but I didn’t know where. And in those moments when I felt lost, I slowed down and I actually opened my eyes to look around to see where I was to ground myself in the space and the music and to take a break from the search.

Dancing gave me the capacity to hold both my memories and the emotions I was feeling in the present moment. In creating these dances, I was able to embody memories, stories and experiences I had only once imagined. I could collage past, present, and future to come to an understanding of how to deal with time and its beautiful way of intermingling. Dancing helped me become more whole — more connected to myself and to my greater self that included my family’s rich history. Dancing was my therapy and my connection to my culture.

Soon I started reading more and more about the therapeutic benefits of dance and realized that that was my calling — I wanted to give others what dance gave me: a sense of calm and peace within myself and a loving connection to my past. So I became a dance/movement therapist.

Through my healing journey — through my dancing journey — I learned that in addition to inheriting my family’s memories and traumas, I also inherited their resilience. My family members are survivors. I feel my own resilience when at the sound of an Arabic song my body can feel at ease. With all the complexities my mind went through to understand my identity and my history, the most connected I have ever felt to Babylon, to Iraq and to Iran, have been when I am dancing. Through dance I can celebrate, but I can also mourn the loss of a home generations before me were forced to give up and that I will never get to see. Through dance, I can go home again. Through dance, I can move with my family’s history, like a dance partner or an old friend. Together, we glide through time.

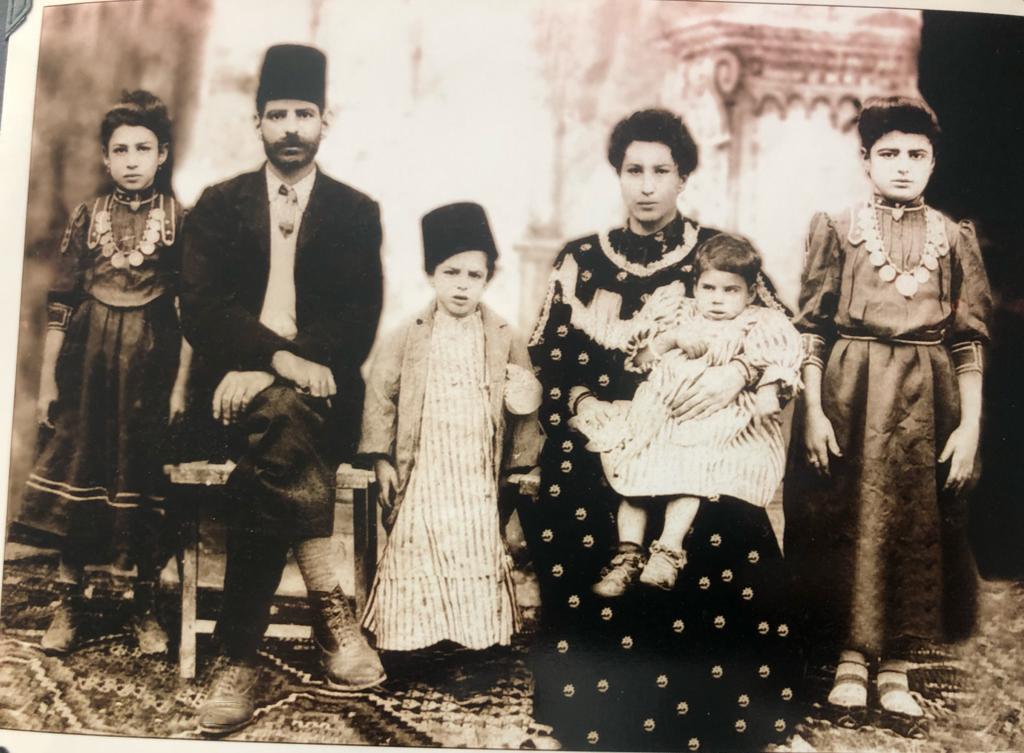

When I hear the music of my culture, like magic, my neck, arms and torso all know how to move — as if my ancestors awaken inside me at the first bang of the drum. My neck elongates like a snake, my hips create smooth figure eights as my wrists gently articulate my fingers. My eyes close and I feel my spine moving through the air with ease and comfort. My breathing becomes even and my eyes glisten, open to the present. I am reminded of the strength it took for my grandfather to make the difficult and emotional call to move his family from Iran to New York, of the selflessness my mother showed when she sacrificed going to the university of her choice to support her family through the difficult transition, and of the power our community still has — just in the fact that we still have a synagogue that prays the way my great-great-grandparents prayed in Iraq in the early 1900s and beyond.

To remember and know their resilience is to allow their resilience to live on. That is the greatest honor I believe I can grant my ancestors: to move with all they have given me.