A woman moves to a small town from London to escape her former life as a high-powered TV executive, only to get caught up in a strange murder mystery and receive threatening, anonymous calls to her new home.

A woman escapes to an expensive spa retreat in Arizona to face personal problems, but instead comes face to face with a girl who’s been dead for several years — America’s “most famous murder victim.”

A woman avoids a cop on the street where a man has just been murdered, and she falls under suspicion as meanwhile someone posts a “men seeking women” ad that discloses intimate details of the murder scene.

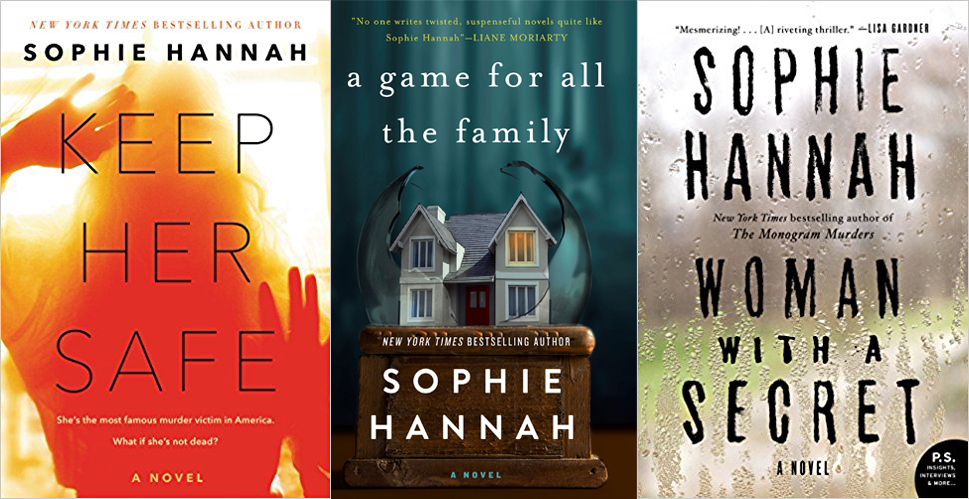

All of these describe the sickeningly captivating plotlines of Sophie Hannah’s female-led mystery novels, to which I am currently addicted. No, this is not sponsored content. This is just praise from a woman who is obsessed with mysteries by women, starring women, and frequently attempts to solve them before the books end (with an under 50 percent success rate). Hannah is the latest author I’ve encountered who fits this niche, and, besides Tana French (whose books don’t always star women, but I’ll let that slide), has become one of my all-time favorites.

The only author whom Agatha Christie’s estate has licensed to write books featuring the famous, fictional detective Hercule Poirot, Hannah has traveled well beyond what’s come to be informally known as the “Gone Girl genre,” where unreliable women get involved in outlandish, twisted crimes. She even wrote poetry that both grade school and degree-level students study in the UK. Based on her work, one can surmise that Hannah is clever, inventive, British, a big mystery fan, and maybe even a little bit twisted. One probably wouldn’t surmise that her mother is Jewish and was born in the British Mandate of Palestine.

I actually discovered that Hannah came from a Jewish background when I recently searched her name and found a story written by Jewish News Online, “Britain’s Biggest Jewish Newspaper.” The article made no mention of Hannah’s religion or even cultural background, but the fact that the Jewish News Online published a story dedicated to the author made me wonder.

Turns out, Hannah’s mother, Adele Geras, is Jewish and also a writer. She’s even explored Judaism in many of her works. “Passionate” about teaching kids “history through fiction,” Geras has included moments from Jewish history time and time again in her stories, according to The Jewish Chronicle. She has written both adult and children’s books that touch on Kindertransport, rescue efforts that got Jewish children out of Nazi Germany between 1938 and 1940, and has covered topics like “generations of Jews [living] in Jerusalem” and “Jewish immigrants sailing to America.”

While Hannah’s stories remain firmly secular in subject matter (at least, the ones I’ve read), they don’t fail to make cultural commentary. In Keep Her Safe (alternatively titled Did You See Melody?), a woman’s spa retreat is turned upside down after she sees a girl, Melody, whom the whole country believes to have been dead for seven years. The girl’s parents have been in jail nearly that whole time for committing her murder. What led them there was, in part, a zealous talk show host whose strong views were able to sway public opinion in disfavor of the alleged murder victim’s parents.

Since we currently live and breathe in a country that’s run by a belligerent talk show host, Keep Her Safe feels relevant and incisive. Do you trust what you see with your own eyes, or what you’re told on TV? How much should we allow the media to influence us? I found myself asking these important questions even though I was reading what I’d imagined (and hoped) to be a mindless, trashy mystery novel. The book never lost its charm as a result. I was just able to experience the mindless joy in a more…cerebral way.

Overall, Hannah’s plotlines prove more intricate that most in the “Gone Girl genre.” While Paula Hawkins makes her unreliable narrator a blackout drunk in Girl on the Train — an easy copout — and Ruth Ware develops her characters as far as “bitchy gay friend,” “obsessive mom,” and “ditzy blonde” in In a Dark, Dark Wood, Hannah creates real, relatable individuals in her books, whether they’re the supposed “good guys” or bad.

That’s what good mystery writing ultimately comes down to. An author must be able to shed a sympathetic light on so many characters that you’re not sure whom to root for and whom to condemn. That’s what makes a story mysterious — a bad guy shrouded in a person-like-you’s clothing.

Then, of course, there’s Hannah’s twisted plot mastery. She somehow makes extremely farfetched stories believable — at least believable enough that you’re not rolling your eyes at every other page (cough, cough, Ware). In A Game for All the Family, the protagonist’s daughter writes a creepy murder mystery that may or may not somehow be true to life, and the school her daughter attends seems to cover up the existence of a former student the daughter claims to be her best friend. The plot only gets less plausible from there.

But Hannah’s lead in A Game for All the Family, a woman so fed up with her demanding life as a TV executive that she’s escaped to a quiet town where she relishes the idea of telling people she does “nothing” for work, approaches what’s going on around her with such a believably neurotic attitude that it’s hard not to get behind her. As she attempts to wrap her head around one unfathomable circumstance after another, I found myself nodding along with her actions. Yup, that seems like what I would have done if my daughter’s principal insisted her real best friend was completely made up.

Hannah may not have examined Judaism in her writing the way her mother did. It may mean very little to her religiously and culturally (when I reached out, Hannah was unavailable for comment). But I believe part of why her mysteries succeed in a way that others of the Gone Girl variety don’t is that she embraces the complexity inherent in every dark tale and in every thinking human. She captures neuroses in a way that only someone who grew up with a Jewish mother can.

Maybe this is a stretch, or maybe it truly does take one to know one (I, too, grew up with a Jewish mother). Either way, I recommend Hannah’s novels for anyone hoping to keep their neurotic brain deliciously occupied, Jewish mother or not.