Once upon a time, the opportunity to be a “NJB Poster Child” for the day was a dream come true.

Nine years ago, at age 15, I was invited to speak about my Jewish upbringing at a luncheon in my hometown for an organization of Jewish women working on social justice community projects.

My younger sister was pissed and jealous. “You’re not even a woman!” she exclaimed. She was right. The situation was tender and silly and l’dor v’dor at its core: a group of almost exclusively 65+ year-old women looking towards a scrawny, baby-faced, and male-identifying me to deliver a State of the Union about young Judaism in my rural western Massachusetts community. I was unassuming, affable and MLB-box-score-obsessed — an apparent “NJB” through and through.

For those not familiar with the term: the “Nice Jewish Boy” is a catch-all phrase used to describe an iteration of Jewish man. The “NJB” is, well, nice (think soft smiles and polite Shabbat Shaloms), emotionally sensitive (they’ve cried before! Baruch Hashem!) and basically competent (probably, like, makes his bed, or something).

That day at the luncheon, I lived up to the image these women were looking for, above and beyond. I crushed my speech. Timing of Biblical jokes? Impeccable. Pacing? On point. Fit? Marvelous: Red Sox t-shirt, my-everyday-blue-jeans with an ambiguous yellow stain on the knee and frayed New Balance sneakers.

The reaction was both astounding and familiar. Clusters of retired women swarmed me with plates of catered food and the phone numbers of various granddaughters. It was a formal induction into NJB-hood. I was ready and willing. I thought: I could get used to this.

I went to a heteronorm-y and Judaism-barren public school, about as far from Boston as you could get and still remain in the state. Typical toxic masculinity reigned, without much room for pushback. Amongst the boys who were my peers, stoicism, muscles and degrading your friends’ mothers were rewarded. I did not fit in with this rendition of masculinity.

I spent most of my time feeling decidedly uncool and unsexy. But amongst the bubbie rave at the luncheon I was invited to speak at, everything was different. The things that were intrinsic to my being, the characteristics that usually had led to feelings of otherness or rejection, were celebrated in this environment. Being myself was exactly what these older women wanted from me. I felt like I was glowing.

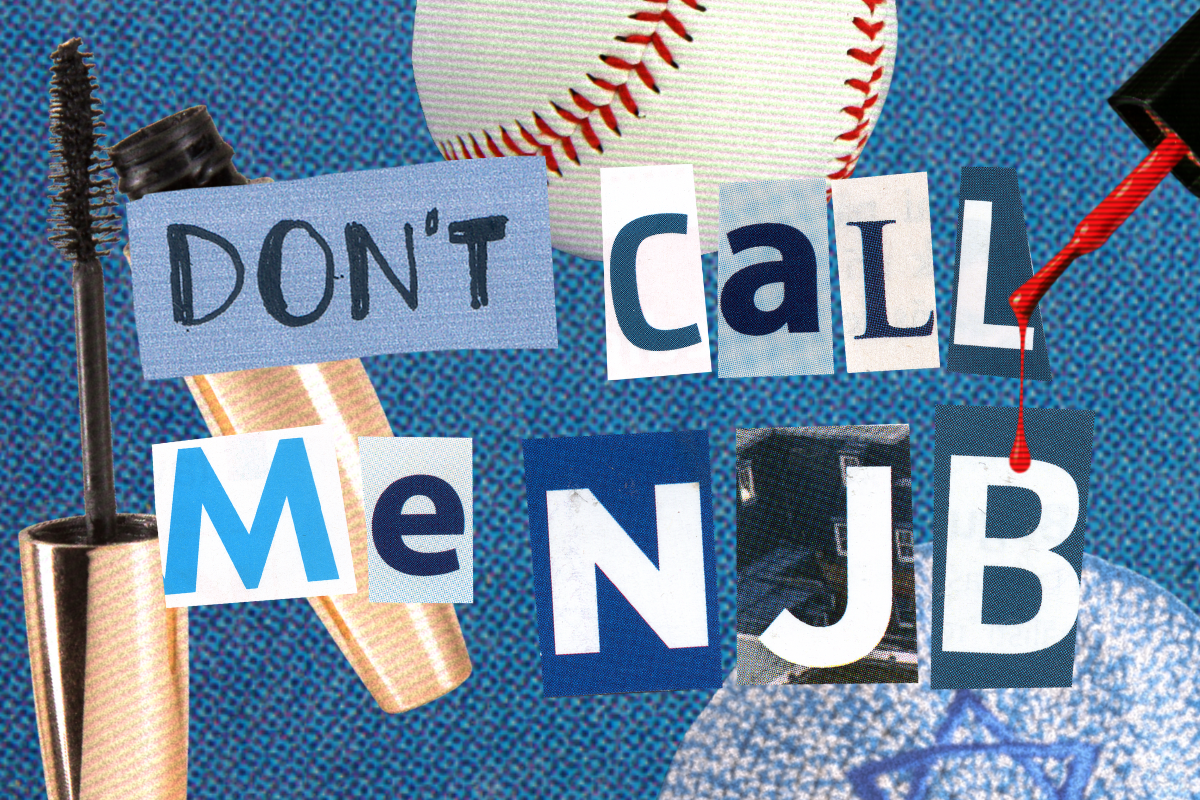

This was a high moment in my history of being labeled a “Nice Jewish Boy.” But over the years, my feelings about the label and its deeper meaning have changed significantly. Now, almost a decade later, I feel confident that we need to stop fetishizing the “NJB” — and maybe drop the term altogether.

There’s a long history of Jewish people trying to mold Jewish masculinity from a place of fear. At the Second Zionist Congress in 1898, Zionist leader Max Nordau coined the term “muscular Judaism.” In response to Jewish persecution in Europe, Nordau acknowledged and grieved the ways that the Jewish physical body had internalized suffering and trauma. So, he encouraged a new generation of Jewish men to get ripped. Literally. He believed that by reclaiming an identity of physical strength, Jewish men would reclaim Jewish pride from the claws of antisemitism.

To me, Nordau’s promotion of “muscular Judaism” reeks of internalized antisemitism. In trying to reinvent Jewish masculinity, it works within — and remains attached to — antisemitic judgements of Jewish bodies. It insists that Jewish men become strong so that they don’t appear as the antisemitic alternative: weak, repulsive… not enough. This is an approach to gender expression that feels embedded in fear, and wedded to suffering. “Muscular Judaism” provides no room for agency to explore masculinity apart from its relationship to antisemitic stereotypes prescribed upon Jewish bodies.

In a way, maybe the “NJB” queers Nordau’s machismo, pushing back against its hypermasculinity. It imagines Jewish maleness beyond muscles and towards (basic) emotional intelligence and kindness. But while I leaned into the “NJB” praise in my youth, as a masculine-leaning Jewish adult, the term now makes me squirm.

Like “muscular Judaism,” the “NJB” exists only in relationship with harmful standards of not only the idealized masculine body, but also the gender binary. Yes, it presents the possibilities of a more queer masculinity. But, it still doesn’t feel totally free to me. Free of comparison to other masculinities, or gender-based categorization. When I overhear people talking about a “NJB,” it’s: he’s not like other guys…he’s a “NJB.” The “NJB” is always in relationship to what it claims to not be: toxic masculinity.

It leads me to a question that I think we need to let linger. A question that I think can be a guide in holding space for a more vibrant spectrum of Jewish masculinity: What is Jewish masculinity when it is given space to breathe into itself? Beyond the “muscular Jew,” beyond the “NJB,” beyond category and semantics… who are we?

Speaking of semantics, let’s consider the literal words of the “NJB” label. Nice. Nice. Niiiiiceee?!? Personally, I think the Jewish people can ask a bit more from their boy-identifying people than to be “nice.”

And, there’s the glaring “boy” part. Let’s nip the gender binary in the bud when we can.

Whereas when I was a child I was trying to fit desperately into a specific mold of Jewish (and also generally normative) masculinity, these days, I find my gender expression to feel elusive. I like to think of it as one of those little tie-dye bouncy balls you get at an arcade that bounces way higher and more erratically than you anticipate. I feel like I am actively locating it every day, and I want to live in a curious, open relationship with that process. So, in light moments, the “NJB” label can feel neutral-to-sweet to me… but, most of the time, it feels deeply flattening. I invite our Jewish communities to really reckon with the ways we claim to “know” our Jewish male-pals. Maybe, in this process of unknowing, we can create space for a more playful and expansive Jewish masculinity.

This past year, I worked up the nerve to read a poem I had written at an open mic at a writers’ conference I was attending. It was about my deep love of cereal — specifically, Grape Nuts. (If you think it’s rabbit food, you’re eating it wrong. Tip: Add raisins!) I wrote about how, for me, celebrating the joy of eating has helped me heal from years of disordered eating/exercising — years of long-distance running my body out of that extra latke I wanted, in response to dissonance I felt within my masculine-coded body.

I was one of the youngest attendees at this writer’s conference. As I walked up to the open mic stage, I felt the same eager shudder I did almost a decade ago, when I was given the opportunity to express myself as a budding NJB in front of those older women at the luncheon. This time around, my Red Sox t-shirt and New Balance sneakers had been replaced with painted nails, mascara and a ring on every finger. Even though I was performing a different type of gender expression, that tender David Ortiz fanatic still sits inside me. As I read the poem, both selves felt like they were sitting together, inside of me, splashing around in a boyish gender puddle. I wasn’t looking to be identified as a “NJB” — I was simply hoping to be seen as the exploratory, masculin-ish project I feel myself to be.