This year, at 23 years old, I’m going to observe Simchat Torah for the first time ever.

The child of an interfaith home — Jewish mother, Catholic father — I’ve been on a lifelong journey to determine the contours of my identity as a Jew and the extent I want to observe holidays and mitzvot. Though I was raised unambiguously as a Jew, I attended Catholic school for most of my life and ended up celebrating more holidays with my Catholic side of the family than with the Jewish one. I would show my face at High Holiday services only occasionally as a teenager, and even less as a college student. At that point, I concluded that I was agnostic. Yet there remained some element of me that was undoubtedly Jewish — but hard to articulate.

2020 and 5781 have a way of putting things in perspective.

This year, the High Holidays and subsequent fall holidays, including Sukkot, Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, occur only a short time before an extremely consequential presidential election in the United States. We were met, on Erev Rosh Hashanah, with the grim news of Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s death. On Yom Kippur, we were met with the release of President Trump’s shocking (or not so shocking) tax returns. And just as Sukkot was about to begin, news of Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis came. All of this is occurring during a national moment already made chaotic by social upheaval and the pandemic. And for me, the New Year also corresponds to an upheaval in my personal life, as I have just begun pursuing my master’s in religion at Harvard Divinity School after a year off from school.

For these reasons, I’ve been returning to Judaism for guidance and have been more attentive than ever to not just the ritualistic aspect of our holidays, but the messages that they send. I think that Simchat Torah — which roughly translates to “rejoicing in Torah” — is particularly relevant this year of all years, not only for myself but for everyone.

The festival celebrates the conclusion of the year-long public reading of the Torah from Genesis 1 to Deuteronomy 34 and the immediate beginning of the next cycle. During a non-pandemic year, we’d gather in the synagogue to rejoice in the Torah by removing its scrolls from the ark, circling the bimah, singing and dancing, and reading the end of Deuteronomy.

I, of course, will not be spending my first Simchat Torah in the sanctuary because of COVID-19, so I have chosen to observe the festival by reflecting on the message in the final two chapters of Deuteronomy, which chronicle Moses’ final blessing and death upon arrival at the Promised Land and the transfer of power to Joshua.

Leadership during a time of change plays an important role in these last chapters of the Torah. Moses, the great Israelite prophet and leader whose narrative shapes so much of the Torah, is finally on his deathbed after a long journey towards the Israelites’ Promised Land. His final blessing over the Israelites is triumphant and hopeful.

When he passes, the Israelites mourn the loss of their leader for the traditional period of 30 days, at the end of which they move on, apparently accepting the new leadership of Joshua without question. His potential for leadership is not described, but it’s implied in Moses’ decision to name Joshua as his successor, which is commanded by God.

The message here is that while there will be leaders, even good leaders, like Joshua, Moses will remain the quintessential and unmatchable prophet-leader for the rest of history. This favors personal reliance on and connection to Torah and the memory of Moses over reliance on any particular leader of the moment. This message is extremely important for American Jews (and non-Jews!) today.

Like the Ancient Israelites, we are also in a time of change in terms of our national leadership. Simultaneously, I believe we are also at the edge of a promised land, or at the very least a more promising land; both pandemic and protest are exposing the flaws in our fundamental systems, spurring important public discourse about how to address those flaws.

Yet, unlike the Israelites, we do not have a Moses figure to guide us. Depending on your opinion of Joe Biden, there may not even be a Joshua figure in the picture. But, as Deuteronomy teaches us, we don’t need a Moses figure to lead us forward to a better future, so long as we can remember Moses’ wisdom and follow his example.

As there are infinite ways to be Jewish, there are infinite ways to follow the example of Moses. The most immediate way is, of course, to honor and observe Torah, but from my own experience I know that this doesn’t necessarily work for everyone. Besides, there are important practical analogues in our civic and social lives.

For many, emulating Moses will mean exercising their civic duty and voting; for others, it will mean taking to the streets to protest racism, police brutality, and mass incarceration. No matter the method, to follow in the example of Moses is to share in spirit of tzedek tzedek tirdoff, “Justice, justice, shall you pursue,” Moses’s instruction to the Israelites from earlier in Deuteronomy.

While I won’t be dancing with a Torah this year, Simchat Torah has offered me the opportunity to reframe my Jewish identity in terms of the mosaic obligation to justice as I go forth in the New Year.

In light of the pandemic and upcoming election, we should all seek to be leaders to ourselves and others in the tradition of justice established by Moses. It is through the tenacious pursuit of justice that we can help our nation reach a promised (or promising) land that abolishes racist institutions and practices, fights fascism and white supremacy, and uplifts the dignity of all citizens.

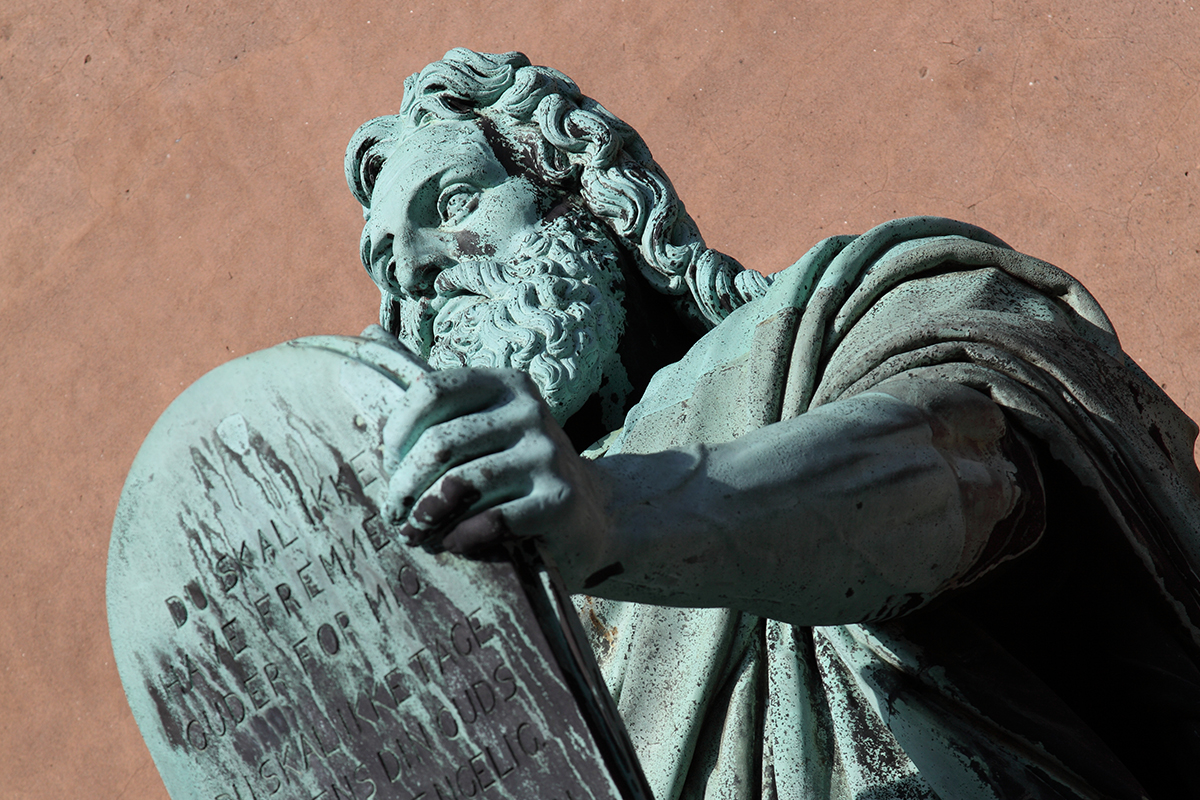

Header image: Statue of Moses, photo by pejft/Getty Images.