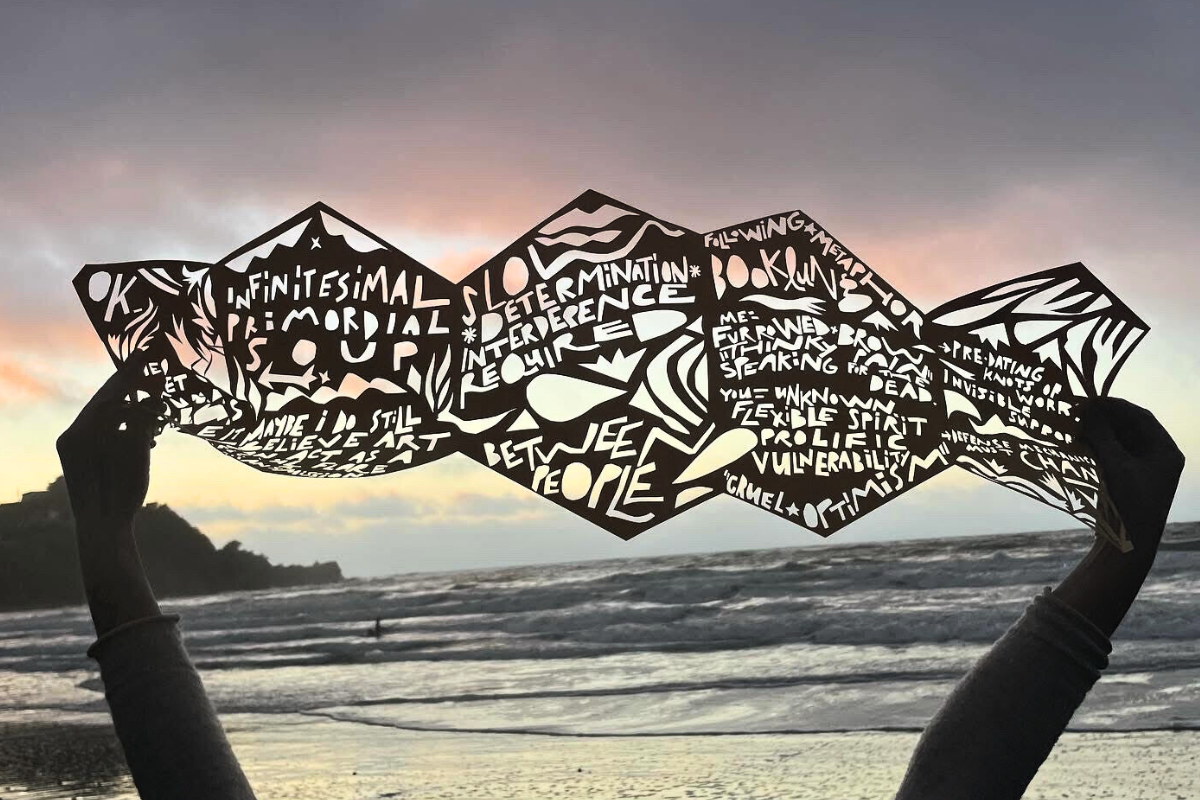

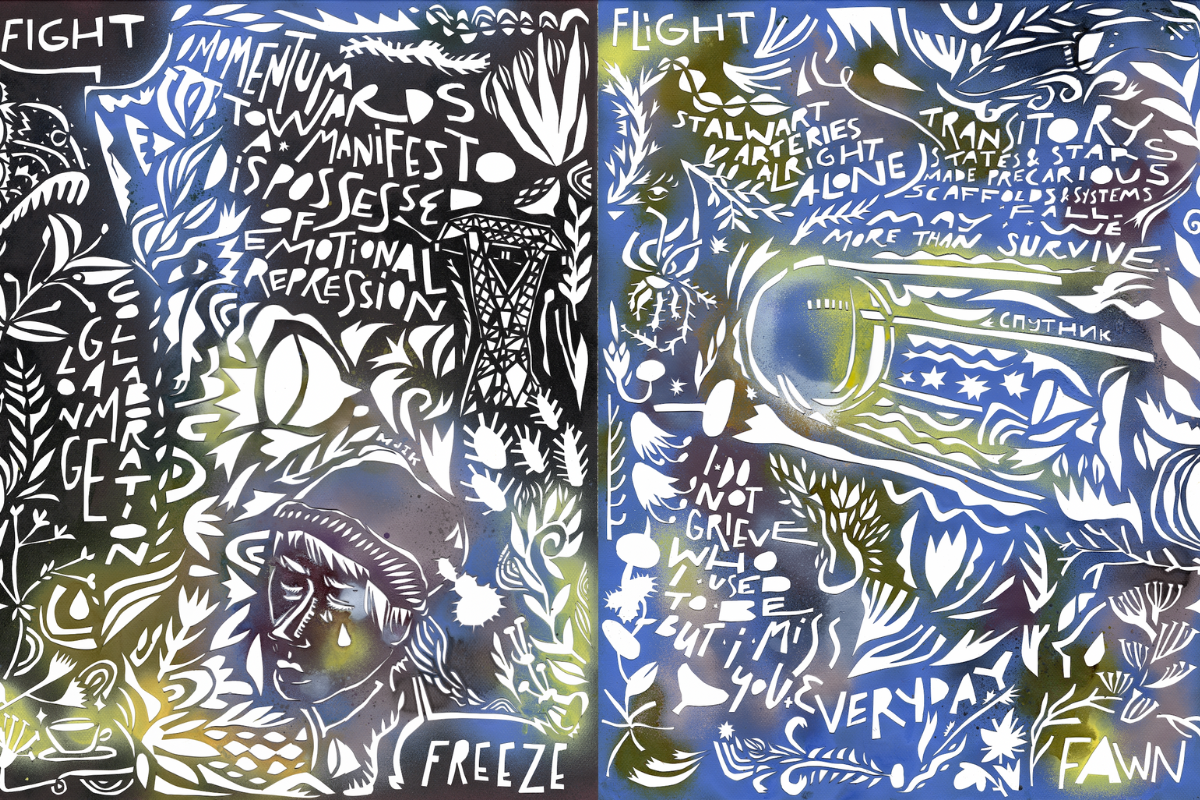

When I stumbled on the artist Kate Laster’s Instagram account, I was immediately struck by her playful use of color that has an effortless spray-painted effect and the bold way she carves out — often jarring — words. Laster (she/they) explores printmaking and paper cutting techniques, carving out quotes or personal explorations, and uses small pieces of tape to laminate the image. At sundown, the artist often floats their paper cutting work onto the water, seeing how the natural elements affect the final piece.

The work is not just beautiful on its own, it is also explicitly political. The Jewish Alaskan artist explores their queer Jewish identity, complex emotions about loss and diaspora, and the concept of tikkun olam through her work.

The 32-year-old artist was born in Anchorage, Alaska and now resides in the Bay Area. While she focuses on paper cutting, Laster’s work involves a variety of mediums, including book-making, various forms of printmaking and public art on the exterior of buildings. Her work is a reminder that contemporary Jewish art cannot be boxed in.

I had the pleasure of chatting with Laster recently over Zoom about how her work connects to Jewish rituals, nature and the constantly evolving political landscape.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How would you define your art?

My work is about the people we carry with us. I do a lot of carving work, so that might be woodcut, relief, printmaking, but it’s also paper cut, and I’m carving away or cutting away to reveal something. I like the idea of revealing something over time, and connecting that to people who are with us in physical space, or generational space, or by coalition.

You were raised in Alaska. What was that experience like as a Jewish person?

I’m really fortunate and lucky to have the parents that I had, and this connection to place. That is part of my work as an artist and a Jewish person. I was raised with story and activism in the sense of places and people. As an anti-Zionist Jew, that’s really important to me — that people is place, community is place. Placemaking involves connecting activism and action into how we treat others. Nature is so, so important to me, and Jewish ritual is tied to nature. I think a lot about tashlich, and a lot of my practice right now is taking these delicate really scrappy pieces of paper cut, putting them in bodies of water and then retrieving them. And that becomes a ritual, as the piece gets to live once it’s in water.

“You deserve safety and care” by Kate Laster

What does your Jewish identity look like to you now?

I’m very proud of my secular cultural Jewishness. It informs this understanding of a history of activism and questioning. Since time immemorial, questioning and advocating for people is part of that Jewishness. And the medium of paper cut also is about accessibility. Here in California, there’s a huge legacy of Papel Picado — Mexican paper cut — and there’s a huge history of Chinese paper cut. All of these things are because of a diaspora. These Jewish ideas are really indelible to who I am. And I think they’re ideas of adaptation, survival and coalition building.

What has it been like to put your work into the world, including on social media?

It’s really weird and beautiful. There are really cool connections of Jews who grew up rural or people who also do papercutting or who also love the idea of humans. I’m really interested in public art and the idea of making art that’s mortal and that’s about finding each other, or making more space to question. My practice of writing and making paper cut and then moving into the world is super tied to this idea of sundown as ritual. Sundown is often when I take my work out to the water. And my dad always connected this idea of the first three stars in the night sky, that’s when it’s night in Jewish practice. Growing up in one of the most visible skies — the Alaska sky is really powerful — I’m always looking to reconnect. So it’s connecting to place and people and being open to just putting your art out there.

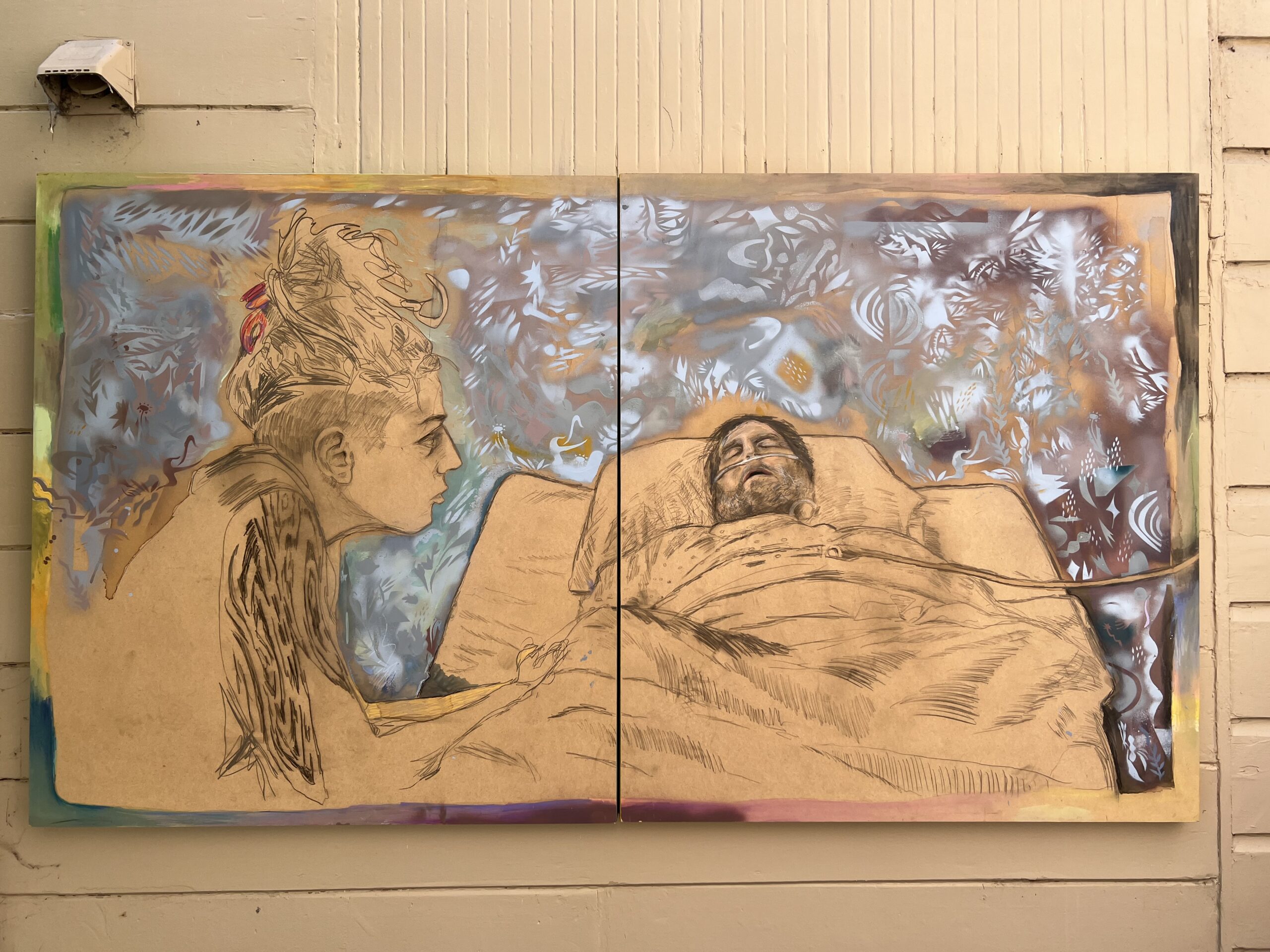

I was looking at your work, YOU WERE HERE, which explores your Jewish family and preserving your history. What was the process of creating that? Was it cathartic?

I started re-working that project in a ghost town in Cisco, Utah and it was a really cathartic process. I think for me, processing complex memory and complex love can be really difficult to process, unless I’m processing with visual art. I like leaving things and seeing if they weather, seeing if they change with the elements. And I’m always thinking about people in my personal life — as a queer Jew, as someone thinking about chosen family and feeling so fortunate with my parents, and understanding [family] is something that constantly adapts and grows and changes. The people that connect us are connected through memory and generational resiliency.

Do you have an idea in mind of what you want the future of your art making to look like? Does it feel like it’ll depend on the political landscape?

I mean, we’re in a constant political landscape, right. And as Jews, too, we’re looking back and moving forward; capacity moves with us and we feel it in different moments. I make very mortal art — that means art that changes in physical space, but then also is transmitted in digital space. I want to keep making work. I think that’s the only way I can consistently formulate ideas.

I have these notes of thinking about accessibility and transformation and celebration. And that’s a huge part of all of this for me, when you can go deep in yourself. There’s this ability to change, and there’s this ability to celebrate. And those are tied to my art rituals, and my surviving Jewish rituals — from tashlich to that casting out into the ocean or into a body of water. And then what is left with you when you change and adapt. I think about that with grief, as well, which is a very important part of what I do as a visual artist and writer, and educator, even. Just this idea that, you know, we enter in and carry loss and absence. And that’s important. And it is a celebration of life.

Check out more of Laster’s work here on her website and Instagram.