I met my friend Reni waiting for the bus that would take us to sleep-away summer camp when she was 9 and I was 10. A painfully shy kid, I huddled quietly by my mom as Reni approached, bag of gummy worms in her hand and Baby-G watch (remember those?) on her wrist, to ask if I wanted to sit with her.

I must have managed a nod, because the next three hours I spent sitting next to Reni, eating gummy worms and timing the drive from Boston to Harrison, Maine. When we arrived at camp, we found we’d been assigned to the same bunk.

Three years later, I was dancing the hora at Reni’s bat mitzvah, and 14 years after that, I was doing the same at her wedding.

As she walked down the aisle a few weekends ago in Brooklyn—not to get too sappy, but I’m already writing a story about enduring friendships, so—for a second I caught a glimpse of the 9-year-old girl I’d first met, all frizzy hair, freckles, and eager smile. Of course, her hair was perfect on her wedding day, and her smile was composed, serene—like she’d been practicing getting married her whole life (she hadn’t been). Cue the tears.

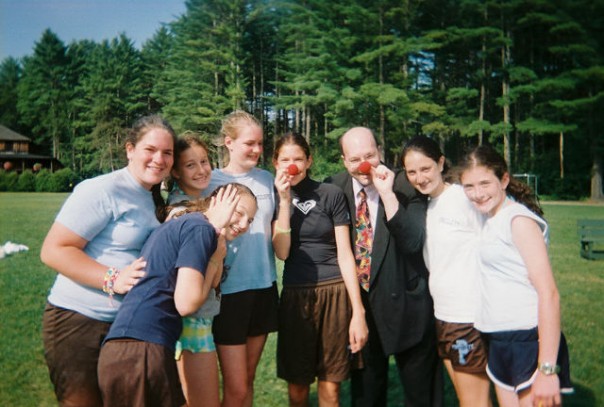

I looked to my left and my right, where our five mutual best friends from camp were sitting, either similarly tearing up or making hushed jokes about the notion of ceremony, tradition, etc.—a common pastime for us—or both. They’d traveled from as far as Idaho and as close as three neighborhoods away in Brooklyn to make it to the wedding that day, vacationing from jobs ranging from speech pathology to massage therapy. It sounds clichéd, but it felt like we’d all been giggling about our most ridiculously domineering camp counselors just last week.

In reality, it had been nearly 10 years since all seven of us had been in the same place at the same time.

Most people have friends with whom it feels like no time has passed, no matter how many years they’ve spent apart. With camp friends, this feeling is even more acute because you go through your first moments of true independence together. Separated from nuclear families, usually for the first time, you have to figure out how to negotiate a world that has nothing to do with them. It’s uncharted territory that you learn to sail—sometimes literally—with other 10-year-olds.

“It’s weird because I feel like I’m accessing a younger version of myself when I talk to you guys,” my friend Emma said, describing this phenomenon. “Like my adult self actually doesn’t have emotions or laughter inside of me, but when I’m with you, I can access a younger version of myself that does.”

While Emma certainly isn’t joyless in her “old age,” as a high school teacher, she does have to discipline unruly adolescents all weekday-long. What makes the camp friendship so valuable for her, in part, is that when she’s with our group, she gets to act that young instead of chastising the behaviors that often come with being 14.

For instance, Emma may or may not have engaged in “stupid adolescent shit like throwing my wine glasses into the East River” at Reni’s wedding reception (sorry Reni) “because that’s totally something my 14-year-old self would have thought is fucking hilarious.” Our 27-year-old selves, after a blink of adult conscience, did, too.

Keeping close friendships from your first taste of youthful independence not only prevents you from losing grip of your childhood self, it also helps cement the essence of who you are and makes your current sense of self stronger because of it.

“For me, there’s an element of comfort knowing I can simply exist and there are years of friendship to back the fact that you all like me,” said Lauren, another close friend who also may or may not have witnessed a wine glass getting hurled into the East River at Reni’s wedding. “Also, I think it was you the other day saying how interesting it is for a group of such distinct women to be friends, but I think it’s because we have an equal sense of loyalty and morals that help us connect.”

Allie, who drove over from Philadelphia for the wedding and had, years earlier, flown from Philadelphia to Boston for Reni’s bat mitzvah, echoed this sentiment:

“Even though we are growing into our adult selves, constantly changing and re-evaluating who we are and what we want, we discover new ways to connect,” she said. But when we see each other, we still have a tendency to “start laughing until we cry while snuggled on a giant air mattress.” (It doesn’t matter where we are—we will find an air mattress to laugh/cry on.)

“Camp was a unique place where we could completely be ourselves, and we have taken that with us in our friendship,” said Hilary, now back in Idaho post-wedding with her dog and fire-jumping significant other (he jumps from planes to fight fires, seriously).

Part of our closeness at camp came out of us being the rejects. We were the group of girls who hadn’t grown up in Westchester or Manhattan, and either as a result or because we just happened to be the kinds of kids others called “weird,” we forged bonds that came out of us truly being and embracing our norm-defying selves.

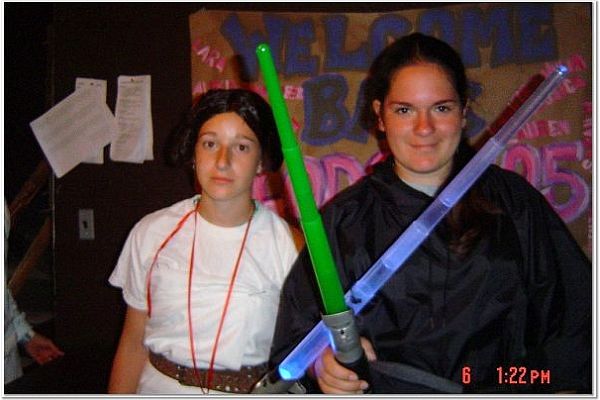

Some of us (cough, cough Hilary, Sarah) ran around camp as 11-year-olds in ponchos carrying brooms, enacting the roles of “the grim sweepers.” Others would sit under a tree during our one allotted time per week for buying candy (one bar), serenading other campers with a song designed to get them to give up their candy for us (it never worked). We were strange, but we were strange together, always finding new ways to applaud and participate in each other’s weirdness.

And we still do. “We’re all still supportive,” said Lauren. “Yet now we are counseling each other about partnership and careers and life goals, rather than breaking rules or huddling in the back of a bunk listening to the popular girls tell us what to do with male genitalia.”

“Instead of twirling in circles until we dizzily crashed to the floor in a contact high, we were drinking, smoking weed… but we still carry that contact high with us. As Emma said: We’re able to access a part of our former selves. Attending the wedding, I felt we were in a bubble—just our friend group celebrating being together. When we attended Reni’s bat mitzvah, I had a similar feeling: that nothing could harm us.”

When we were kids, we predicted that Reni would be the first of us to get married. Nearly two decades later, we were right. Not all of our predictions have come true, like when we’d all lose our virginity or how we’d all live in a giant, decrepit mansion together when we got older, but the most important one has:

We’re still best friends, and that still means everything.