Ever since I was born in 1996, I have been Izzy. Izzy Calkins — yup, that’s me. Except for a few years post-high school where I only introduced myself as Isabel, that name, Izzy Calkins, has identified me for 27 whole years on this planet.

In the style of Jewish tradition, my first name was inspired by my great-grandma Ida: a spunky first-generation American born in Brooklyn to recent Jewish immigrants from Poland. My last name, however, was from my Irish Catholic dad, and it didn’t mean much to me. In fact, I never really thought about my name until I got married — my name was my name. Then, suddenly, I got asked three times in one day, “Are you going to take your husband’s last name?”

I didn’t have an answer, nor did I really care all that much either way; I knew I would always be Isabel, and that was what mattered. But after ruminating on the question for a couple of weeks, I realized that my true feelings about my last name were more complicated. This name would be written on our future children’s birth certificates, on the family tree and on tax forms. It would solidify my place in history long after I die. Dramatic, I know, but important nonetheless.

My fiancé Richard and I talked about it on and off for months. “We could create a new name, a mix of both our names?” I ideated. Richard’s last name is Mata, and I loved the idea of truly blending our families, an equal mix of cultures and traditions.

“Matkins,” I joked.

“Calkata,” Richard added. They both needed some work.

But the reality was that Richard didn’t want to change his name. His last name held culturally significant roots within the Mexican community, and this was important to him. He was proud of his background, and he wanted his children to be proud of it too.

I thought it was a great idea to take his name: I had no emotional ties to my last name, so I would add his and match my future children. Still, couldn’t I just remain Isabel, the same woman I was before I got married?

Days before the wedding, I asked my mom and Bubbe about their first marriages, which both ended in divorce. The conversation turned to Bubbe’s parents.

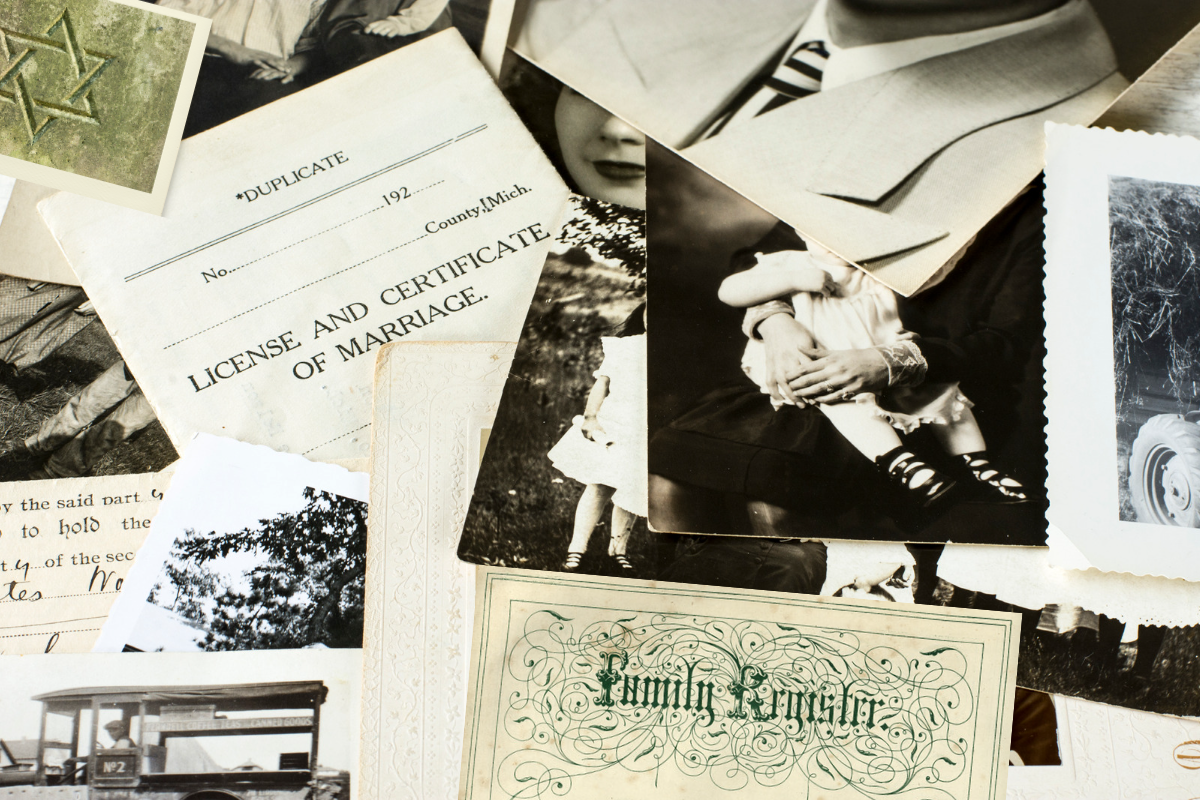

It was 1937 when my great-grandparents, Frances (Fayge) Sapolsky and Alexander Spector, got married. Like the women that had come before her, Frances adopted Alexander’s last name without a second thought. They were both Eastern European immigrants whose parents fled due to persecution and lack of opportunities; taking your husband’s name was “just what you did.” So, Frances Sapolsky became Frances Spector and later gave birth to three kids who would all have that same last name, including my Bubbe.

As far as Bubbe could remember, her mom never had any qualms about changing her name and leaving Sapolsky behind. That likely also had to do with the fact that they lived in Boston and were trying to assimilate into American culture to the best of their abilities. A surname like Sapolsky was sure to give away their background.

When Bubbe was 17, she met Joel, a strong Brooklynite who would later become her husband. They got married in 1963 and, just like her mother, she promptly took her new husband’s last name: Cohen. Their three kids, born a few years later, took on that name. And just as quickly as it came, the name Spector was gone.

In 1986, my mom met my dad at the University of Michigan. They fell hard and fast, getting engaged after graduation and married shortly after. Unlike her mother and grandmother, my mom wasn’t going to just take his name automatically. She wanted a conversation. For the first time in generations, someone had the courage to ask about this tradition.

But like the men that came before him, my dad was stuck in his ways. There was no way that his wife and future children were going to have a different name than him. In less than 10 minutes, it was decided that my mom would take his last name. It didn’t matter that they would be raising their kids Jewish; his family name would be carried on. And just like the names of the women before her, my mom’s name was gone, replaced with her husband’s.

For three generations, the women in my family took the names of their husbands and because of this, on the birth certificates of the children in my family, there was no trace of maternal lineage. This differs from Richard’s Hispanic background, in which children are given both paternal and maternal last names as a way to carry on both lineages.

After that conversation, my decision became clear. If I was taking my husband’s name, I was also going to reclaim my Jewish maternal last name — even if that meant I would, in the eyes of the social security office and my future children’s birth certificates, have three last names. Our kids will be Cohen Mata, a reflection of our marriage and of our cultural identities.

When I told my mom about my decision, she was proud of me for having the courage to do what she did not. My Bubbe, on the other hand, laughed, “Of course you are.” I’ve never been one to shy away from unconventionality, and I am lucky to have a partner who embraces all of me. I’m sure it seems silly to some, going through all that effort to add a name that only a few people will see. But with the recent rise in antisemitism, it’s my way of standing with those who came before me.