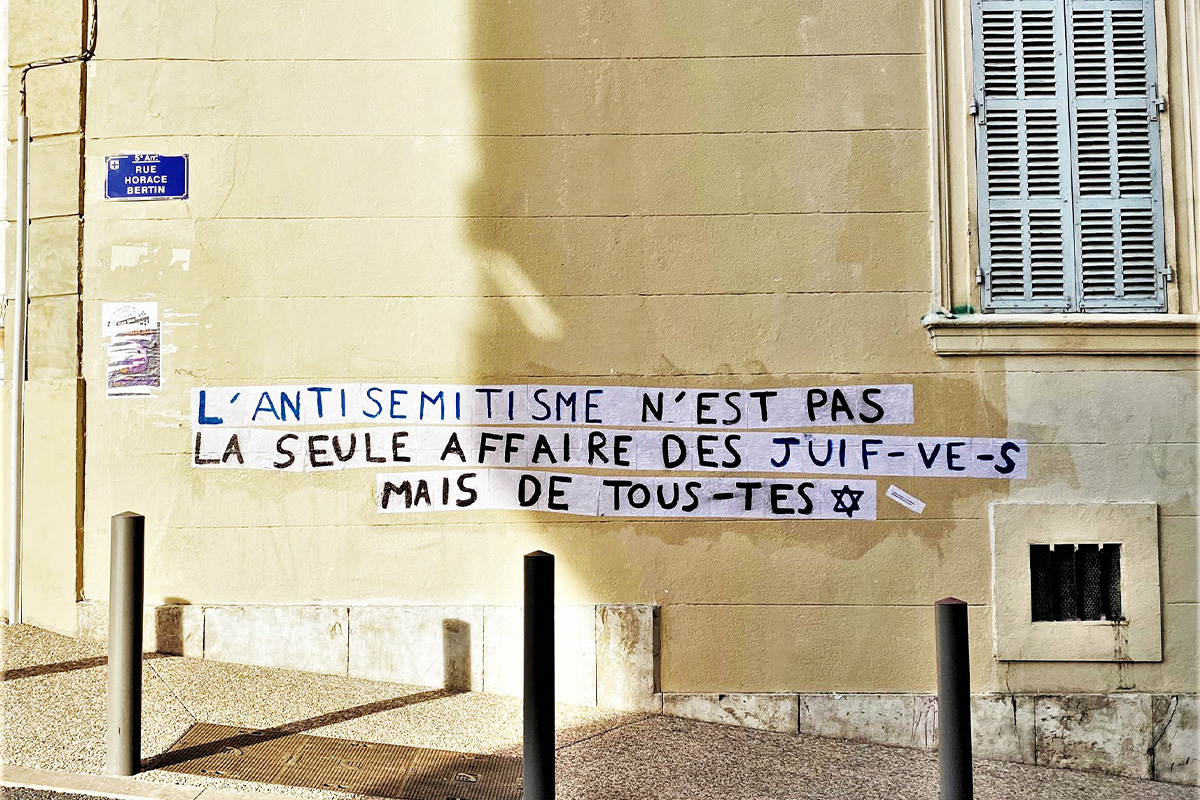

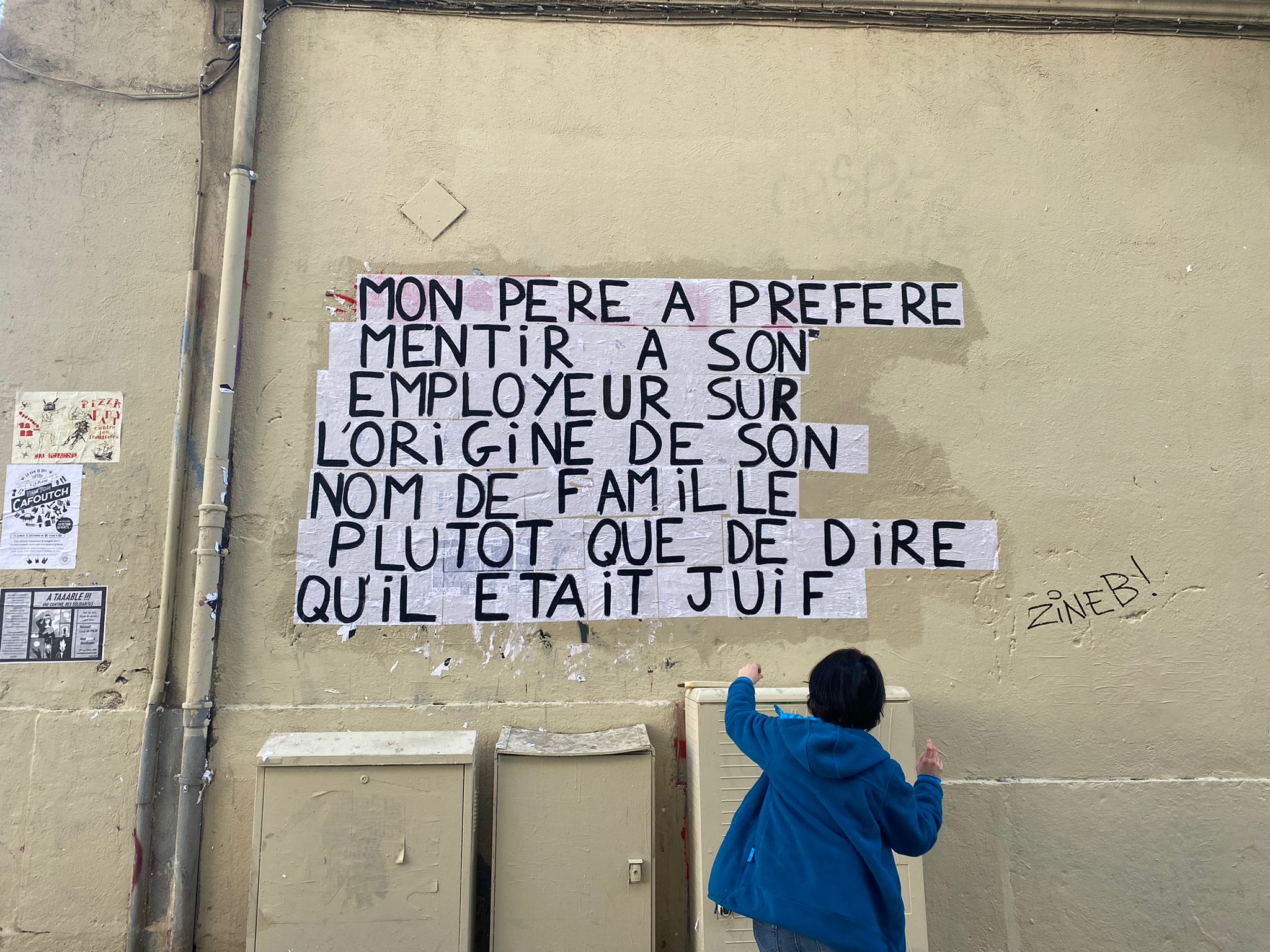

They flourish on the walls of French cities, eye-catching and provocative for those who don’t usually think about these issues: The “collages,” slogans painted letter by letter on paper and glued with homemade wheatpaste to surfaces in public spaces, have become a popular but radical mode of expression for feminist activists. This practice of feminist street “collaging” has taken France by storm in the past few years, and has since spread to 13 other countries. Exploring a wide range of issues from sexual assault and domestic violence to all forms of racism, queerphobia and ableism, many collage collectives describe themselves as intersectional.

As these groups grew larger, some Jewish activists felt the desire to put up messages about distinctly Jewish issues. Pasting well-known activist slogans, but also statistics on antisemitic and patriarchal oppression in France, and messages about political news, the collectives practice strong allyship with other causes that they see as inextricably linked. I spoke with some members of Collages Judéités Queers (“Queer Jewish Collages,” based in Paris) and Collages Fém Juif-ves Marseille (“Jewish Fem Collages,” based in Marseille), two collectives who put slogans about Jewish queer issues up in the streets.

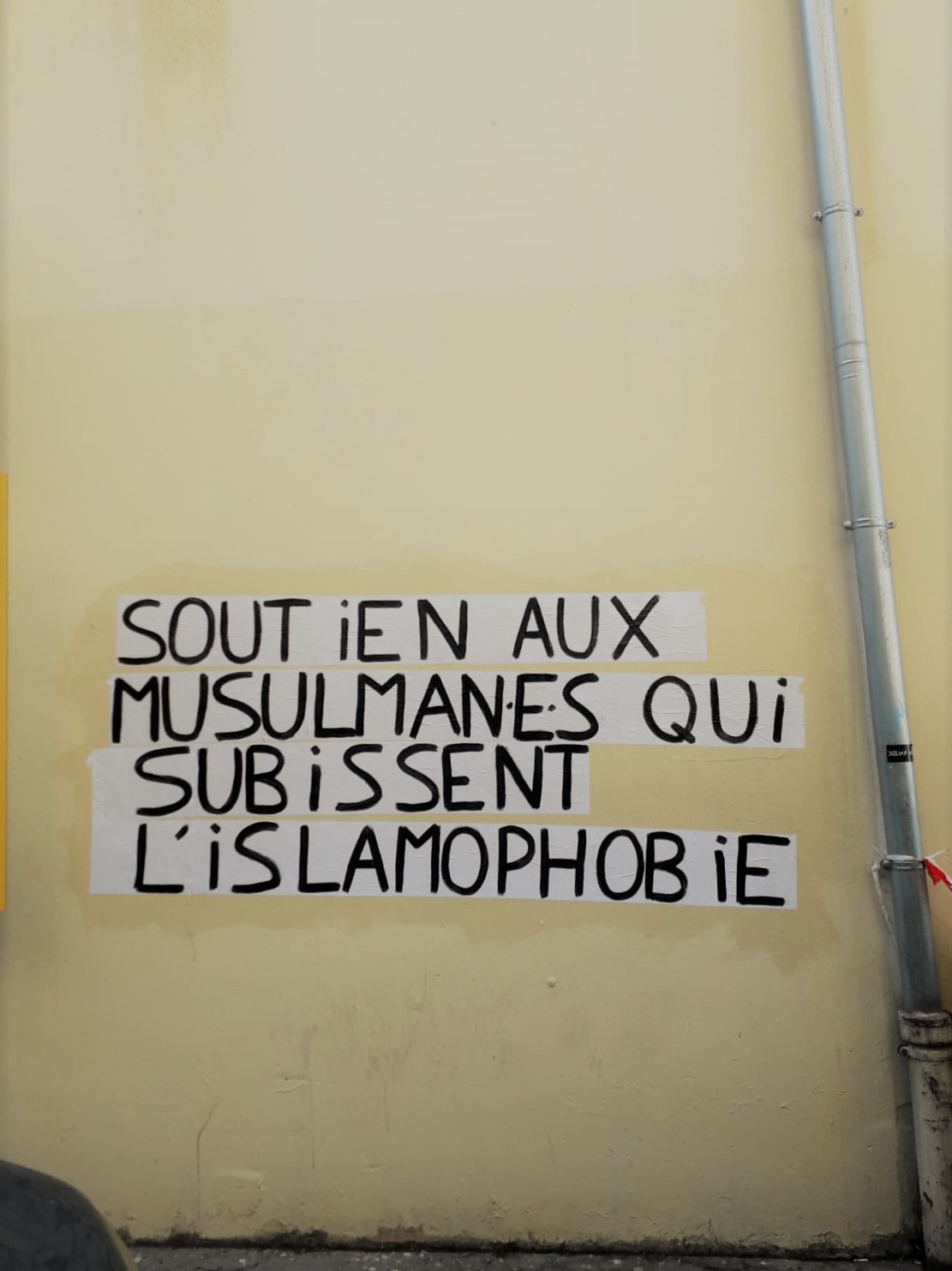

The fight against Islamophobia, whose pervasiveness in France is exemplified by recent partial bans on the veil, is especially meaningful to Lina (Marseille): “It’s important to me to support Muslim women and show our support, because antisemitism and Islamophobia are too often instrumentalized to pit our communities against each other.”

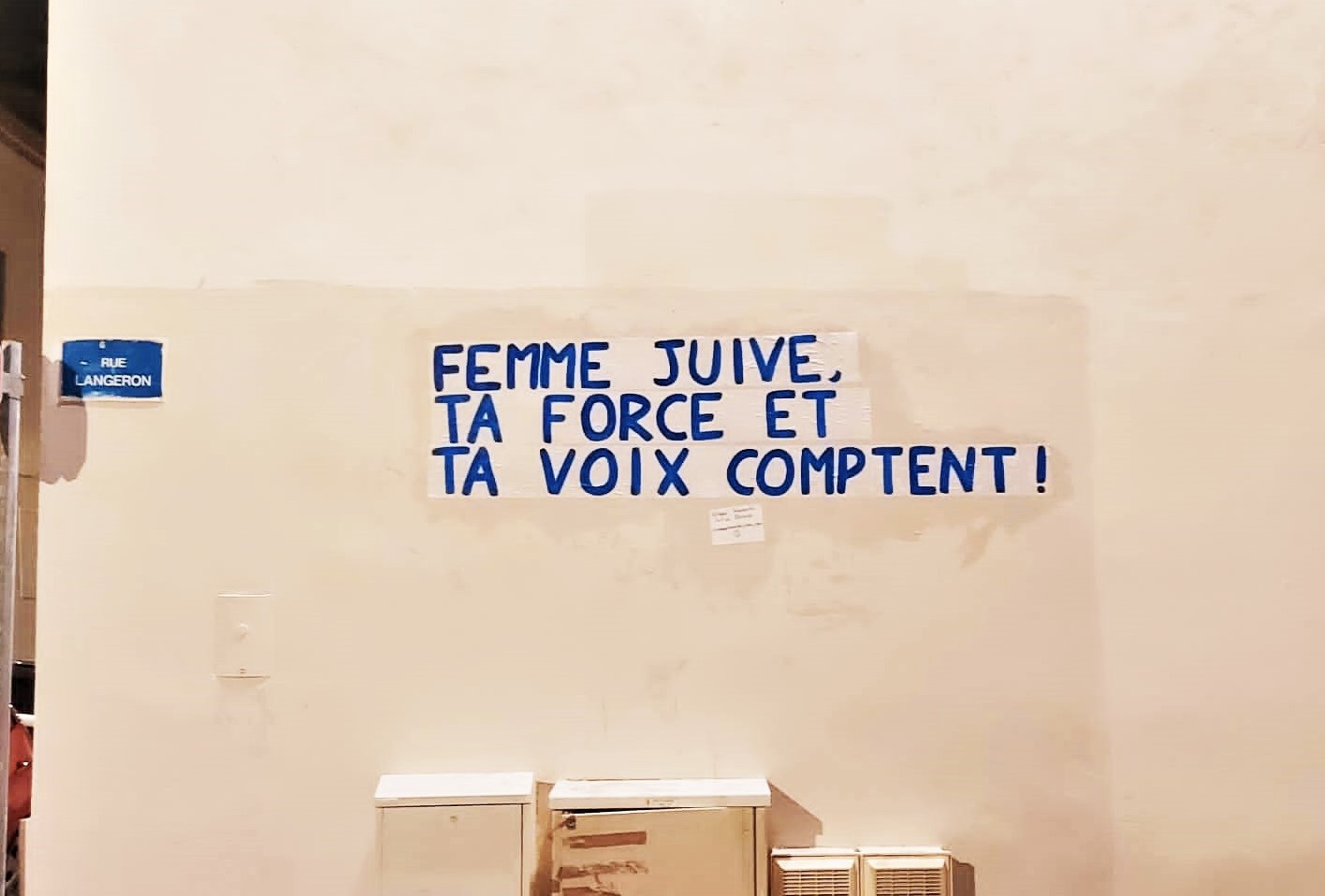

Collages denouncing patriarchal oppression are also a call for the Jewish community in France to work on its own structural sexism: “We pasted about issues surrounding the get, we also pasted ‘we want women rabbis’’” (Liah, Marseille). There are only six women rabbis (like Delphine Horvilleur) in Reform communities in France! Some activists feel strongly that their Jewish identity informs their feminism: “In Judaism, we’re encouraged to question everything. It’s time that we question the place traditionally given to women and LGBTQ people in our community” (Khloe). Liah added, “The art of machloket in Talmud (constructive conflict in Torah interpretation) allows us to doubt, consider our options, look for new ones, and never accept oppression.”

Both collectives also center a memorial practice by pasting about the murders of Sarah Halimi and Ilan Halimi and the 2012 Ozar Hatorah attack, among others. Abel (Paris) says: “One of our current projects is to create a memorial with the names of the 13 people who were assassinated in France since 2000 because they were Jewish. May their memory be a blessing. And although we always think about our dead when we’re collaging, we can’t forget that their memory needs to be active and long-lasting. We can’t just commemorate them and accept the political and social conditions which killed them, and still threaten to kill us.”

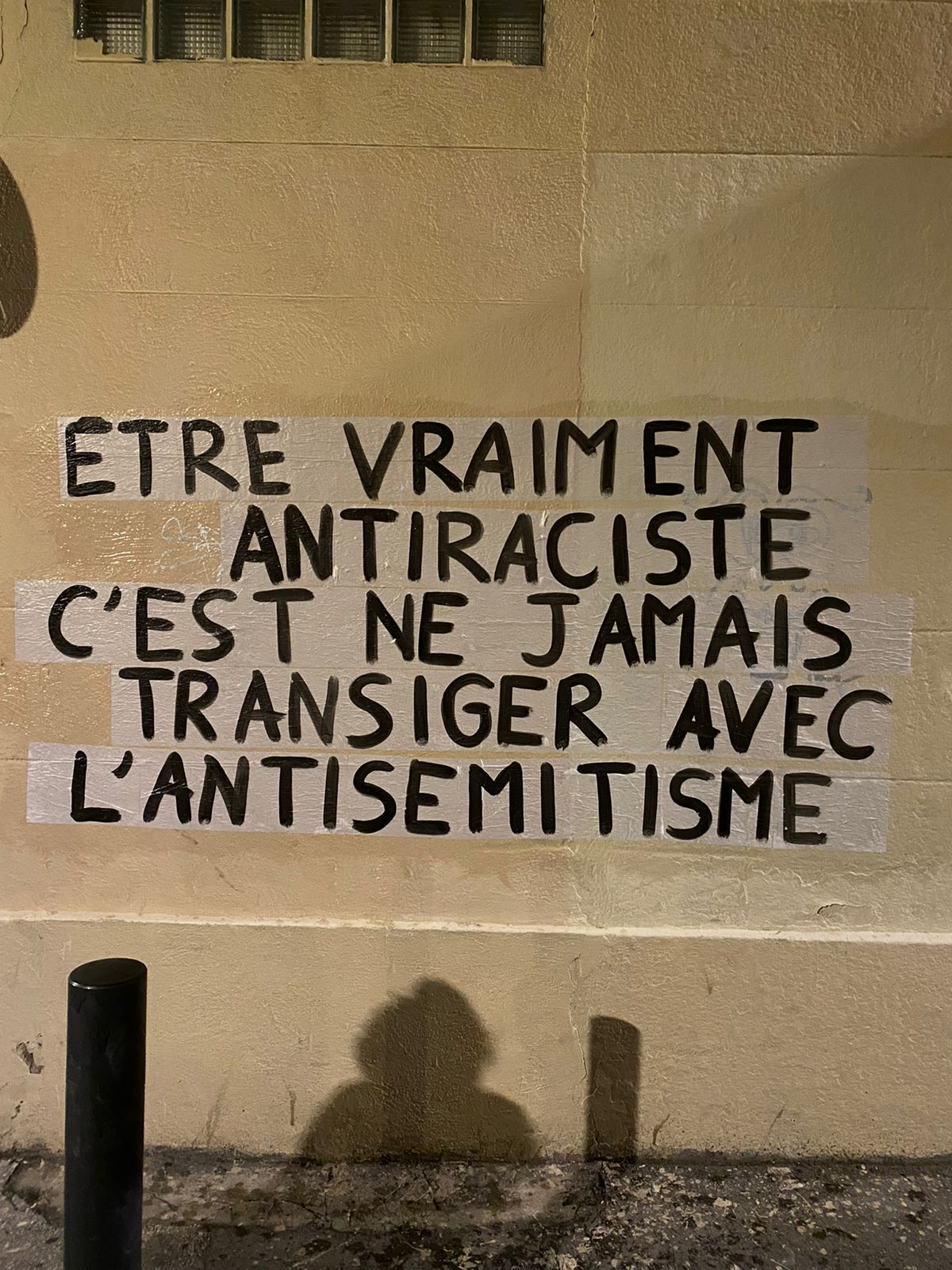

Most of these activists were already involved in collage-making or leftist activist spaces before joining Jewish collectives, but felt the need for a specifically Jewish community — not only because of the looming threat of far-right antisemitism. “It’s hurtful that leftist spaces don’t recognize the discrimination we face daily, and I usually don’t feel comfortable to talk about my Jewish identity,” explains Lina (Marseille). Alek and Abel, who met at an antiracist Pride march in Paris, both describe the difficulties of navigating leftist groups during times of increased tension and violence in Israel and Palestine. Alek says: “None of the activists, whether white or non-white, talk about what Jewish people go through, except when denouncing Israeli policy (for good reasons, incidentally). I felt the need to make my experience visible, to hear it, read it, see it, paint it on the walls.”

What’s so special about the “collage” format? Some mention its accessibility, and the empowerment of finally doing something concrete: “I love the DIY aspect of it” (Charlie, Marseille). Most importantly, many activists mention a desire to reclaim a public space that they don’t usually feel safe in as queer and/or Jewish women and femme people. Lina (Marseille) says: “This action takes place in the street and at night — it’s transgressive. It’s a reappropriation of a space that we cross but usually don’t stop in. We’re in a group, less likely to be approached. We don’t change sidewalks when we see a man, we don’t force ourselves to look away. We walk more freely.”

During those night sessions, people walking by often stop to look, question, encourage or reprimand activists. Liah (Marseille) describes: “Reactions to our work vary: Sometimes people come to thank us (although only women do this) or ask what the message is about. Once, someone even asked ‘Antisemitism? What is that?’ Sometimes people are angry because it ‘damages the walls.’” People’s unpredictable reactions and the risk of potential interactions with law enforcement keep the groups focused: “It’s a rush of adrenaline, and pride once we see the message on the wall” (Charlie, Marseille). “It’s important to be fast and efficient — our goal is to get the collage done. Our vulnerability, physical but also legal, prevents us from doing more pedagogy in the moment” (Abel, Paris).

A lot of activists shared stories of particularly stressful nights punctuated by verbal and physical threats and men getting in the way, clenching their fists and kicking the collagers’ bags. “One ‘thank you’ is worth 10 insults,” Lina (Marseille) says. “Negative reactions encourage us to keep going: We’re supporting victims and shaking up aggressors, oppressors and the system that enables them” (Abel, Paris).

Pasting specifically about Jewish issues comes with its own set of difficulties: “The word ‘Jewish’ is always the hardest one to paste on the wall during our sessions, because of all the tensions surrounding it. We usually keep it for last in the sentence we’re pasting. When we walk by a collage in the following days, it’s often the first word someone tried to tear down” (Abel, Paris). In Marseille, a city with a lot of grassroots organizations and street art, people are more used to seeing this type of street messaging: “It’s rare, but sometimes a collage will stay on a wall for months” (Liah). Usually, they are torn down much more quickly, and sometimes don’t even make it through the first night.

The transgressive aspect of the practice contributes to forming strong bonds between the members of the collectives. Outside of the night sessions, they meet to discuss their commitments and goals, and they support each other when morale is low. In Paris, this solidarity materialized this past summer into picnics organized to provide a safe and welcoming space for queer Jews. In Marseille, some members are building community through shared Rosh Hashanah seders and Algerian Jewish cooking classes, among other activities. “Collages can create beautiful friendships!” (Lina, Marseille)

Both collectives are young and remain quite small (11 members in Marseille) but mighty, actively posting on Instagram and going out regularly to put up more collages. They are inclusive of all people who identify as Jewish, regardless of their relationship with faith or “exact” Jewish heritage.

Feminist activism is finding new, meaningful ways of expression. Brazil, Canada, Israel, Germany and the U.K have all seen collages pop up in their cities, and the “collage movement” reached the U.S in 2021 with Feminist Collages NYC, which also has a number of Jewish activists. By encouraging others to raise their voices and shed light on patterns of violence which have been ignored for too long, the collagers are reclaiming spaces in which they have been historically targeted. As Liah says so eloquently: “The pandemic caused an increase in conspiratorial thought, and made us realize we had to strike back, even if it just means being openly Jewish and proud. An important slogan for queer communities is ‘Our pride is political,’ and as a Jewish person I think that taking proud in our Jewishness is extremely political.”