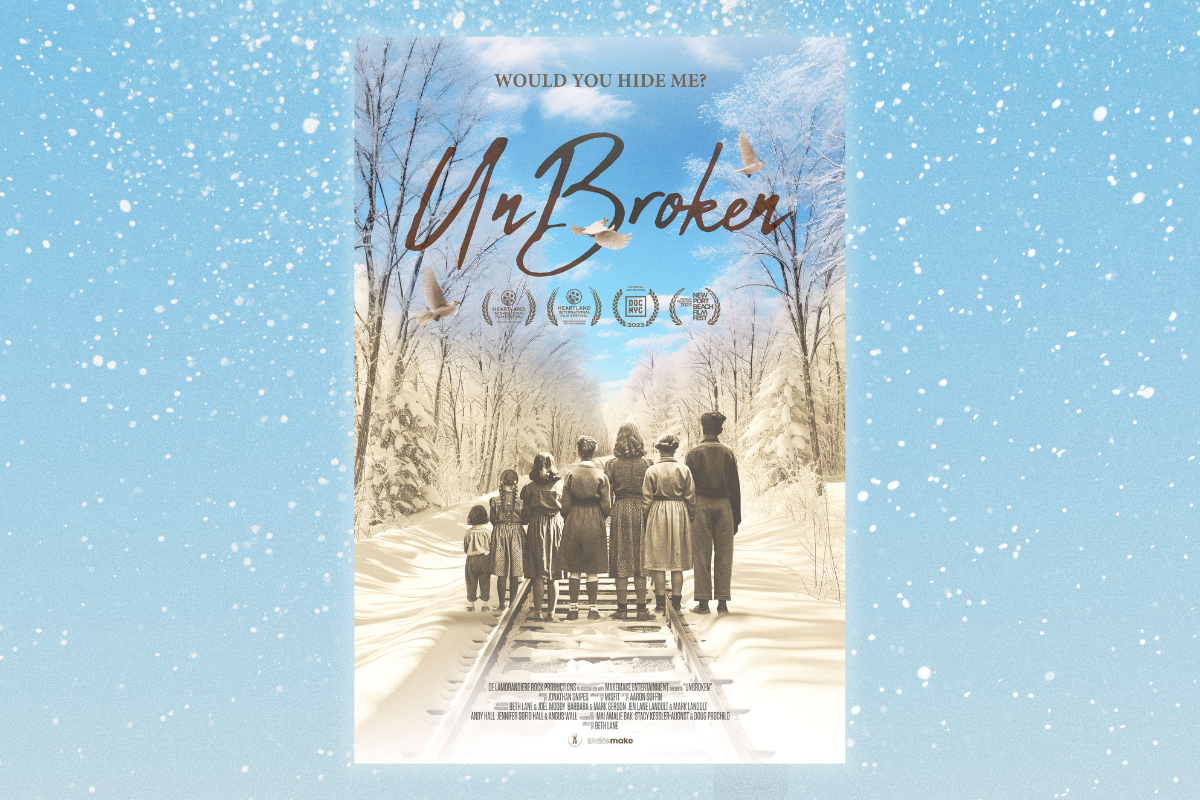

“UnBroken: Would You Hide Me?” is a documentary that tells the incredible story of seven siblings who escaped Nazi Germany together, only to be separated when they arrived in the United States. Created by Beth Lane, the daughter of the youngest sibling, the film debuted in the fall of 2023.

The film chronicles the siblings’ life from the very beginning. Born to Alexander and Lina Weber, the seven Weber siblings watch the increasing violence and discrimination of their fellow Jews as Nazism takes over Germany. After their mother Lina is murdered at Auschwitz for her resistance activities and the threat rises for all Jewish folks in Nazi controlled territories, their neighbors, Arthur and Paula Schmidt, help hide the seven children on their farm for two years. Told by their father to stay together no matter what, the children escape to the U.S. after declaring themselves as orphans. But after their harrowing experiences, the seven siblings are separated when they arrive in the U.S. They don’t all reunite for more than 40 years.

Director, writer, executive producer and founder of the Weber Family Arts Foundation, Beth Lane felt compelled to tell her mother Ginger and her six elder siblings story after Lane and her mother visited the farm where the children hid. The film was in production for six years, and is now on the film festival circuit. “It has been an honor and a privilege that my family has allowed me to carry the mantle for them, because I certainly wouldn’t be doing any of this without their blessings,” said Lane, when Hey Alma spoke with her about her documentary. “I hope I have made them proud.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why is this an important story to tell?

When we first went to Germany, we visited the farm where [my mother] and her siblings were hidden. When we came back to America, three weeks later, Charlottesville happened. Even in my very early stages of shooting [“UnBroken”], I went to film in Charlottesville. I needed to go to a place where people were marching down the streets in the United States of America, bearing swastikas.

That’s really where we began. We started to film; we started to cobble together a rough cut, and little by little more antisemitic experiences were happening globally and around the country. You keep hearing things from the Anti-Defamation League or Jewish World Watch that antisemitism is on the rise. I’ve been giving that rebuttal by saying, “No, it isn’t on the rise. It is here. It is a fixture in our community.”

Then our world premiere was in Indianapolis at the Heartland International Film Festival. It occurred on Oct. 8; it was extraordinary to me that it occurred one day after the most horrific bloodshed against the Jewish people [since the Holocaust]. The universe is saying [the film] needs to happen right now. When the universe talks, you have to listen.

We just have to keep getting the film out there. We’re at festivals right now and we’re thrilled about that. But we want to get this into the homes of children of white supremacists.

What was something surprising that you found making this documentary?

There’s an extraordinary artist Gunter Demnig in Cologne who for the last 27 years or so has been creating these Stolpersteine, or stumbling blocks, out of brass or bronze and putting them in the ground. They have the name of the persecuted, their birth date, if they have died, their death date and where they were murdered. It’s his way of commemorating the dead. He’s got these blocks in about 27 different countries.

We’d been on a waiting list for a couple of years to have [one] created for my grandmother, Lina. The Stolpersteine Initiative and the Berlin Mitte reached out to us and said, “Would you like to have nine bricks, one for her husband and all seven [children]?” I said, “They weren’t murdered.” They came back to us and said, “We have expanded the art installation to include anyone who was persecuted at their last known domicile or place where they were seen before they were deported.” [I got permission from my mother and her surviving sibling.]

We had the ceremony in September, honoring my grandparents and their seven children. It was printed in the newspaper Berliner Zeitung, and a hobbyist researcher saw the article and somehow reached out to me. He said, “I have found this photograph in the archives. Is it possible that this photograph that I found is your family?”

[While I’m hesitant to open attachments from strangers], there was something about this that felt very genuine. I opened up this file and in less than eight tenths of a second, I recognized every single person in the photograph. It was my mother, her siblings and their father. This was in between the period after Liberation before they left Berlin and the displaced persons camps. We have zero photographs from that [aside from government photos and a few baby pictures.] I wish we had more of that [slice of life photos] so that we can really understand what their life was like when they were living in Berlin.

Could you talk about your experience at the farm in Germany where you met the grandson of your family’s saviors?

There’s no question that the day that I made the commitment to make the movie was the day that I met Arthur Schmidt’s grandson. When I met his grandson, I realized that my whole life I had been looking at this story in a very myopic way, I was looking at it from my point of view, from my family’s point of view. When I met Schmidt’s grandson, I was so blown away by the presence of his grandfather, but also hearing his own personal stories. His experience in life was so extraordinary; that was the day I decided I had to make a movie. It was the only way I could say thank you to his grandfather and his grandfather’s wife, Paula.

What’s one thing you want people to take away from this film?

If you’re going to take away one thing: What is it that you are doing in your life that is making someone else’s experience in life better? What are you doing to promote hope in the world? What are you doing to promote hope in yourself?