I acknowledge the unceded sovereigns of the land on which I write today — the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples. I pay my respects to Elders past, present and emerging. My following perspectives are a product of the lessons taught to me by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, for which I am immensely grateful.

* * *

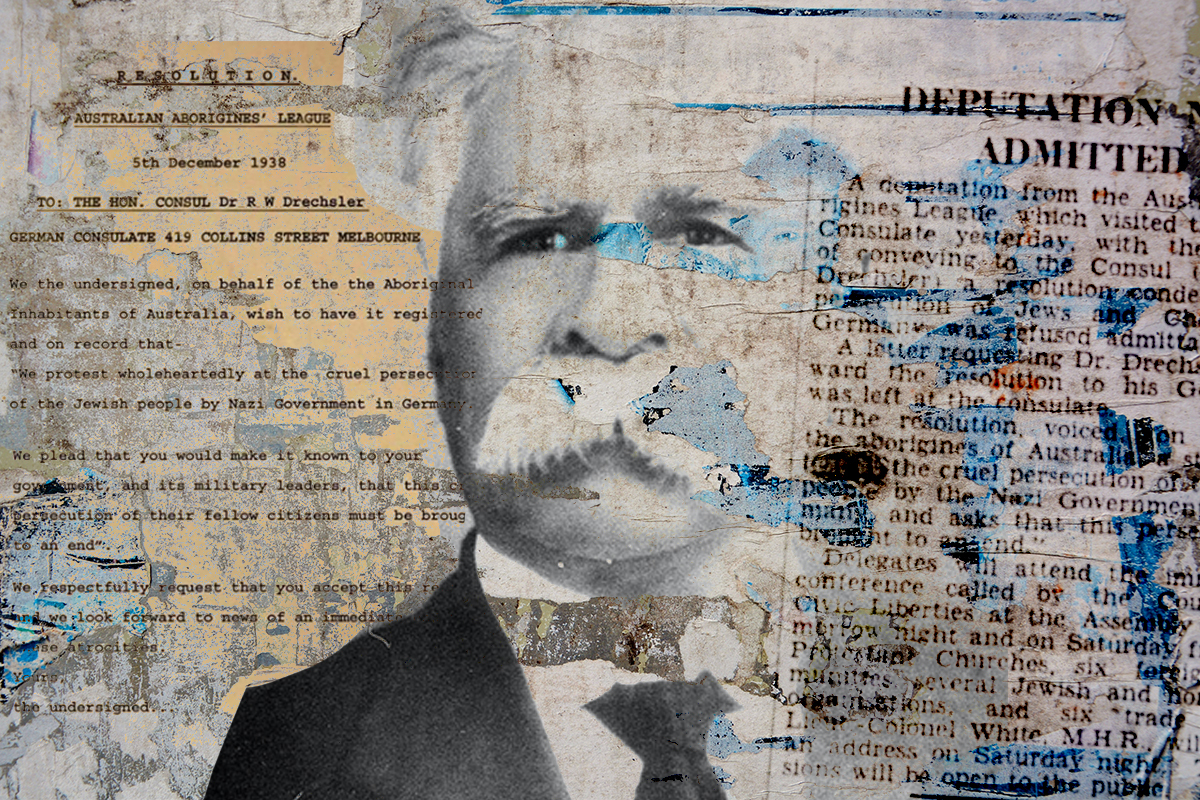

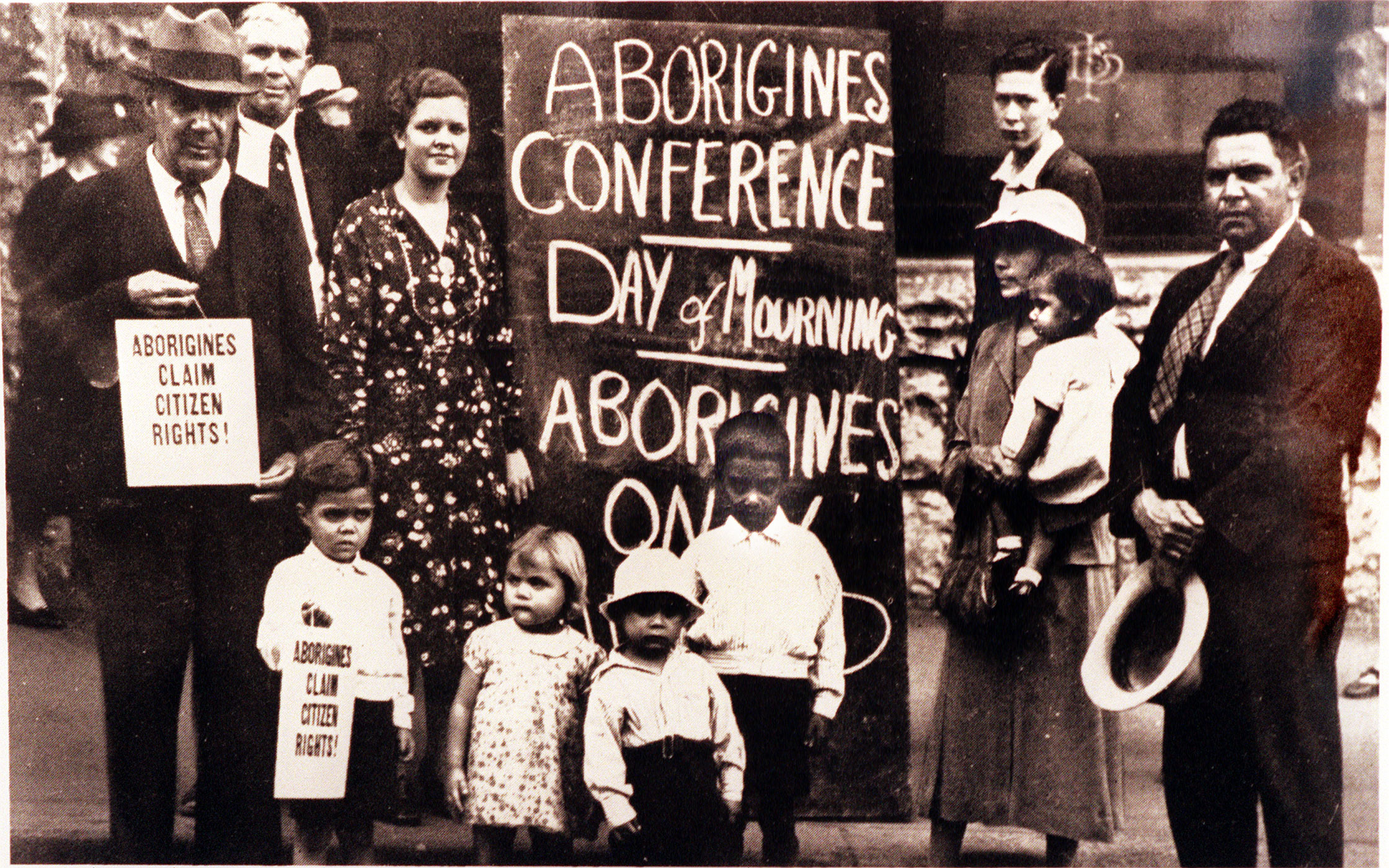

On December 6, 1938, the Australian Aboriginal League embarked on a 10-kilometer march across the streets of Melbourne, Australia. Formed two years earlier by Yorta Yorta Elder William Cooper to advocate for Indigenous rights, the League had an abundance of reasons to protest. Despite inhabiting the continent for over 60,000 years, in 1938, Indigenous Australians were yet to have citizenship rights extended to them, were denied the right to vote in federal elections, and faced the omnipresent threat of paternalistic, state-initiated attempts to displace their children. Yet on this summer evening, the League took to the streets to protest the persecution of a different marginalized group, a community they had never met: German Jews.

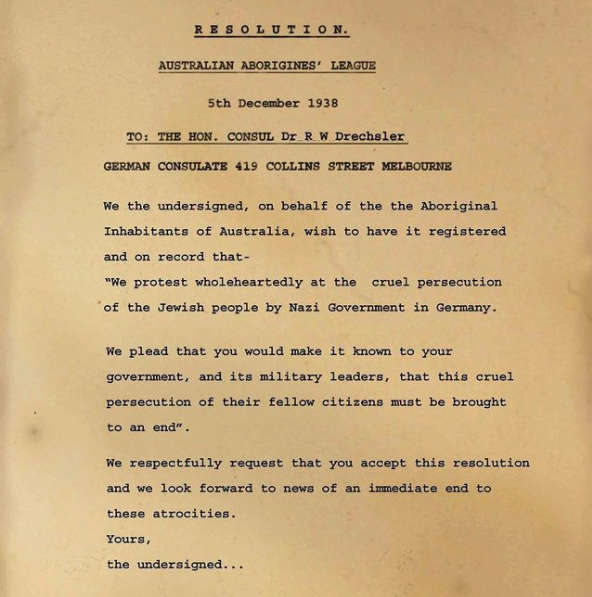

William Cooper’s protest was in response to Kristallnacht (“The Night of Broken Glass”), a pogrom against German Jews led by the Sturmabteilung, the Nazi party’s original paramilitary wing. Overnight, an estimated 30,000 Jews were incarcerated, over 1,000 synagogues vandalized and at least 91 killed. Intervention on part of the German authorities was absent and the international community failed to break diplomatic ties with Berlin. The only (known) private protest against the night’s atrocities was that led by Aboriginal Australian activist William Cooper. Marching towards Melbourne’s German Consulate, the 77-year-old activist gripped a letter, reportedly reading:

“On behalf of the Aboriginal inhabitants of Australia, we wish to have it registered and on record that we protest wholeheartedly at the cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi government in Germany.”

Given the status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in 1938, entrance to the Consulate was barred and Cooper’s letter remained undelivered. It’s likely that Cooper was unsurprised by this reception, particularly given that five years prior his petitioning of King Edward for Indigenous representation in Australia’s federal parliament had received a similar fate. But he marched nonetheless, spurred by the parallels he drew between the experiences of European Jewry and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Prescriptions of racial inferiority were certainly shared, as well experiences of attempted ethnic cleansing. It’s estimated that between European colonial intrusion in 1788 and the turn of the 20th century, Australia’s Indigenous population had plunged by at least 80%. Unbeknownst to Cooper at the time, over the ensuing seven years, European Jewry would decline by 57%.

The majority of Australians remained unaware of the League’s protest — an indictment on the erasure of Indigenous narratives of resistance from Australia’s collective memory. That Cooper’s protest is not a household tale and source of national pride in Australia is a product of racism. We, as Jews, have a duty to rectify this.

Let’s fast forward to today. Australia houses the world’s ninth-largest Jewish population at approximately 115,000. Jewish Australians (or Australian Jews, as the age-old debate goes) came to Australia as an immigrant community. It’s speculated that the first Jewish people to arrive on Australia’s shores were eight convicts on the First Fleet. Although coerced via their convict status, they nonetheless stepped foot on Australian shores as uninvited visitors, pawns in a colonial project that continues to displace and dispossess First Nations Australians today.

By the 1820s, European Jews were arriving in Australia as free settlers, often fleeing European antisemitism. Australia’s first synagogue was erected in 1845 in Hobart, Tasmania. Less than two centuries later, there are around 70 synagogues scattered across the nation. Jewish Australians have access to Jewish leisure centers, eateries, ambulances and graveyards. And, like the meeting places of all communities in Australia, these services operate on Aboriginal land.

Indigenous paradigms teach us that humans are made of Country, the sentient natural environment and land to which people belong. In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, the relationship between people and Country is reciprocal. By nourishing us, Country becomes a part of us, and we a part of it. Us non-Indigenous Australians have thrusted ourselves onto Country and benefited from its nurture. This truth cannot go unacknowledged.

Colin Tatz wrote of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-Jewish relationship as one of disappointment. Writing in 2004, he argued that unlike the civil movements of the United States and South Africa, Jewish participation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advocacy had been lackluster. He outlined that much of our community’s action languished at “multicultural” events, where Jews asked their Indigenous co-attendees the age-old “what can we do?” — a conundrum requiring significant emotional labor from the respondent. In fact, at one of these events in 2003, Kunjandji and Kuku Yalanji woman and first Aboriginal magistrate Pat O’Shane told her Jewish audience to hang its head in shame at its history of lack of support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander movements.

I certainly hope that we’ve improved since 2004. And there are numerous promising Jewish-Indigenous partnerships that speak to this. Either way, however, Australia has a long way to go in the way of makarrata (truth-telling), which every Jewish person can play a role in expediting. In the way of protest, we can step into Cooper’s footsteps and spearhead Jewish contingencies at annual Invasion Day rallies (January 26), protests against Indigenous deaths in custody, and demonstrations against the destruction of sacred Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sites. We can continue amplifying Indigenous calls for a formal makarrata commission, a constitutionally enshrined voice to parliament and the establishment of a treaty between our government and Indigenous Australia. We can even install solar panels on our rooftops in a transition to cleaner energy, heeding the calls of Torres Strait Islander peoples who are on the frontline of rising sea levels.

It’s important to reiterate that Jews don’t merely owe support for Indigenous resurgence because of what Cooper did for us decades ago. For Australians, advocating for Indigenous causes is the bare minimum we must do as residents of the over 250 Indigenous nations Australia encompasses. For the international Jewish community, it’s an opportunity to live out our ethos of tzedek, tzedek, tirdof (justice, justice, you shall pursue).

And, as fellow human beings — as William Cooper taught us — it’s a fundamental must.