Before going on Birthright, my mom offhandedly said to me that I’d probably be the only one in my group with tattoos. This wasn’t stated with pride. She’d always been against my getting inked — once even threatening to disown me. Clearly, she ascribed to the idea that nice Jewish boys and girls don’t have tattoos.

She was wrong.

I got my first tattoo in 2013, when I was 19 years old. Though it was small and took only about five minutes to complete, it was a big deal for me. First of all, I have a tremendous fear of needles, which caused my leg to shake as the tattoo artist began the tiny little asterisk on my right ankle. But bigger than that fear was the dread I felt about how my parents would react.

I didn’t tell my mom about it; she found out a couple weeks later and refused to discuss it. In the months that followed, I got my second tattoo — a daisy on my left ankle. That one she saw the day I got it done. She stormed out of my room and didn’t speak to me for the rest of the day. To this day, we don’t speak about my tattoos, even when I get a new one.

As for my dad, I learned the rumor from him growing up that Jews can’t be buried in Jewish cemeteries if they have tattoos. Yet he understood the symbolism behind my tattoos, what they meant to me. Now he just shrugs, tolerating each new quote or symbol I decorate myself with.

I have 14 tattoos now — a fact my parents have just had to accept.

The good news is I’m not alone. In fact, many young Jews have been getting tattoos — some even directly related to Judaism.

Ari, a 27-year-old man from Iowa, got his first tattoo at age 18. It’s on his wrist and reads “אני חי,” or “I’m alive.” Now, all but one of his tattoos are Judaism-themed or in Hebrew.

“I’m religious. But I’m also addicted to tattoos,” he tells me.

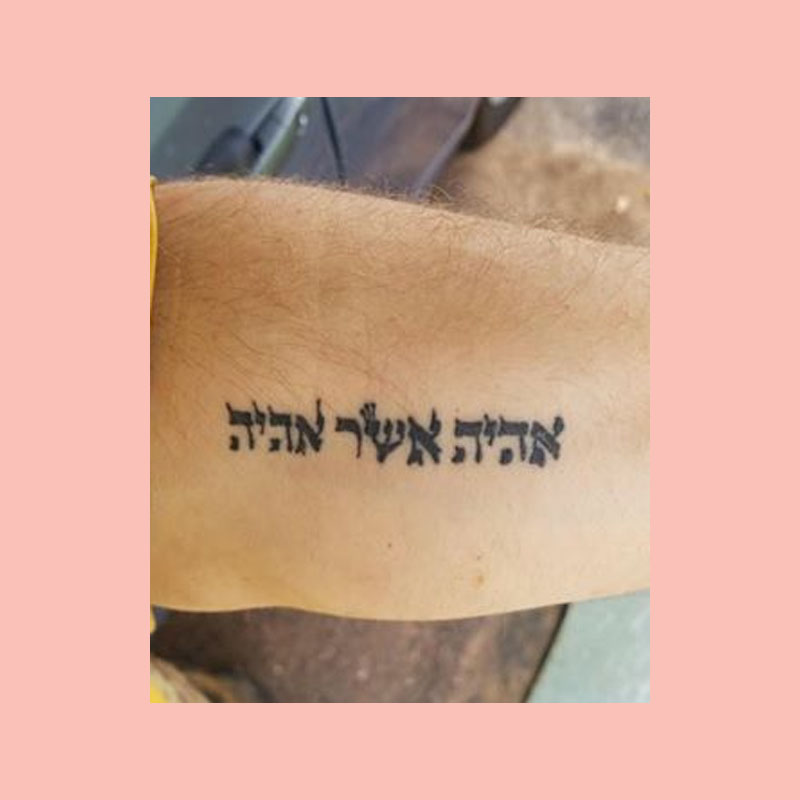

Gabe Siciliano, a 26-year-old living in New Jersey, got his first tattoo last year. It is a quote from Exodus 3:14 — “I am that I am” — in Torah script on his left forearm. It’s a provocative placement, considering the location of concentration camp tattoos.

“I grew up religious, but have lost faith over time,” Gabe told me. “Now I strongly identify as culturally Jewish, but still celebrate major Jewish holidays with my family.”

Speaking of family, Gabe’s mostly thought it was a terrible idea to get a tattoo, especially considering the Holocaust. But they have since come around after learning how much it meant to him.

Elizabeth Levy is a 23-year-old from New York. At age 21, she got her first tattoo — also on her forearm. It’s a song lyric that reads, “Life flows on within you and without you.”

Her mom, being a tattooed woman herself, was fine with this. Her dad, on the other hand, was vocally against tattoos while she was growing up. In her Jewish sorority at college, she was the only one with tattoos.

Worse, non-Jewish members of her family have made insensitive jokes about the placement of this tattoo.

“I’ve actually been teased about it before and asked by non-Jewish family members to ‘show me your numbers,’” she recalled.

“If you are a Jew and you don’t get tattoos because of the historical context, you are allowing the Nazi regime to continue to police your body,” Elizabeth said. “As a Jewish person, getting tattoos [has] been empowering because it’s an act of reclamation of my body.”

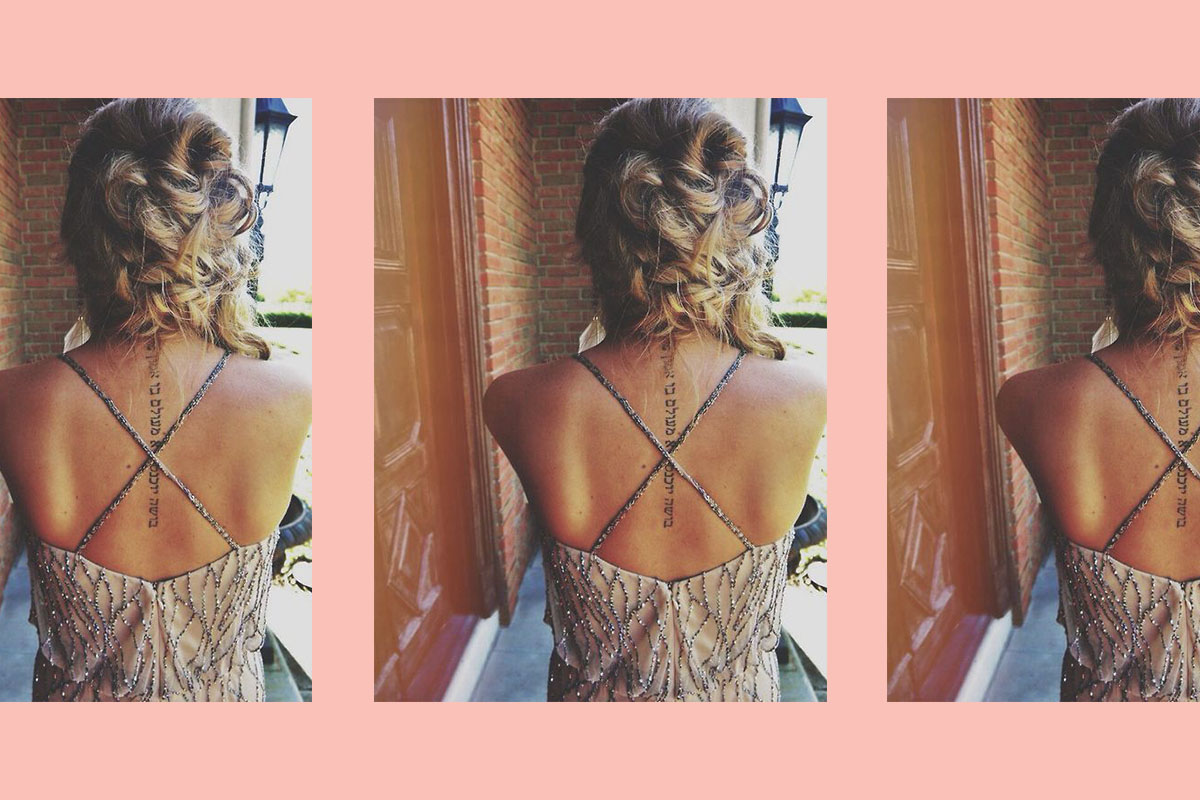

27-year-old Alex Weiss got her first tattoo at age 15, despite being raised in a Jewish household and going to Hebrew school twice a week growing up.

“I didn’t tell my family about my first tattoo for a long time because I knew my dad and grandparents would react poorly,” she told me.

“My family hates the fact that I have tattoos — partially because we’re Jewish but also because I’m a woman. Even to this day, although my family knows I have tattoos, I try to wear long sleeves and covered shoes so they’re not visible.”

“I think the reason parents don’t want their kids to have tattoos has a lot more to do with tattoo stigma than it does with Judaism,” Alex added.

Sarah Schwartz, a 27-year-old woman, got her first tattoo at age 25. Now she lives in Morocco — a majority Muslim country. Before she moved, she got another tattoo in Hebrew.

“It’s an excerpt from Tefilat Haderech (the traveler’s blessing): ותשלח ברכה במעשה ידינו (And may he bless our works),” she explained. “It’s drawn in the shape of a hamsa, and it’s on my ribs. I chose that excerpt in particular because I wanted to get a new tattoo to specifically mark the beginning of my journey to do field work for my dissertation, and it’s in the shape of a hamsa because I moved to Morocco, and [the] hamsa is a symbol shared in Judaism and Islam (in Islam it’s called the Hand of Fatima; in Morocco it’s actually often called a khmisa). Morocco is a Muslim country with a deep Jewish tradition.”

“I heard at some point that Jewish people are supposed to be buried without any modification to their bodies,” she added, “but it never really struck me as a Big Thing; that is, it never felt like a specifically Jewish rebellion for me to get a tattoo.”

Let’s circle back to that burial thing, shall we?

On my aforementioned Birthright trip, while in the Old City, I asked the rabbi who was guiding our group about being buried in a Jewish cemetery with tattoos. He called that story an “old wives tale” and told me it would be fine (though still advised me I shouldn’t get any more. I’ve gotten 10 since then. Oops). He’s right: As My Jewish Learning writes, “there is nothing in Jewish law that calls for denying a Jewish burial to an individual with a tattoo.”

You might be surprised to learn that there’s even a tattooed rabbi out there. Rabbi Patrick is a rabbi based in Richmond, Virginia. In 2014, he penned a piece for Patheos about being a tattooed rabbi.

“Every one of my tattoos represents a Jewish theme. That is very intentional on my part,” he wrote.

In terms of the Holocaust and forced tattooing, Rabbi Patrick has this to say:

“The past has the right to influence our decisions, but it doesn’t have the right to veto our God-given brains. Judaism is a relationship — and no healthy relationship is based on emotional blackmail, even about a history as horrible as Europe in the 1940s.”

I spoke to Rabbi Patrick more about being a Jewish person with tattoos and the tall-tales that surround it.

“The idea that you can’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery is a myth. Caring for the dead is one of our greatest mitzvot[commandments]. So the idea that we would cut someone or burn the tattoo off or any number of myths are just that. We don’t desecrate human bodies in burial.”

Rabbi Patrick also urges us to be critical of the history we read. “As far as the history of Jewish people and tattoos, let’s remember that history is written by the historians and historians have bias and prejudices just as we all do,” he told me. “So I am just as biased as a tattooed Jew as a scholar might be in suggesting that tattoos are not kosher. People have to learn what the texts say and what they don’t say, and make an informed decision from there.”

As far as my personal history with tattoos goes, it’s definitely not over. My body is like a scrapbook — I want to adorn it with text and imagery that’s meaningful to me. I want to be able to look at my body when I’m older and remember what it was like during different periods of my life.

I’m glad to have discovered that when it comes to being tattooed and Jewish, I’m definitely not alone.