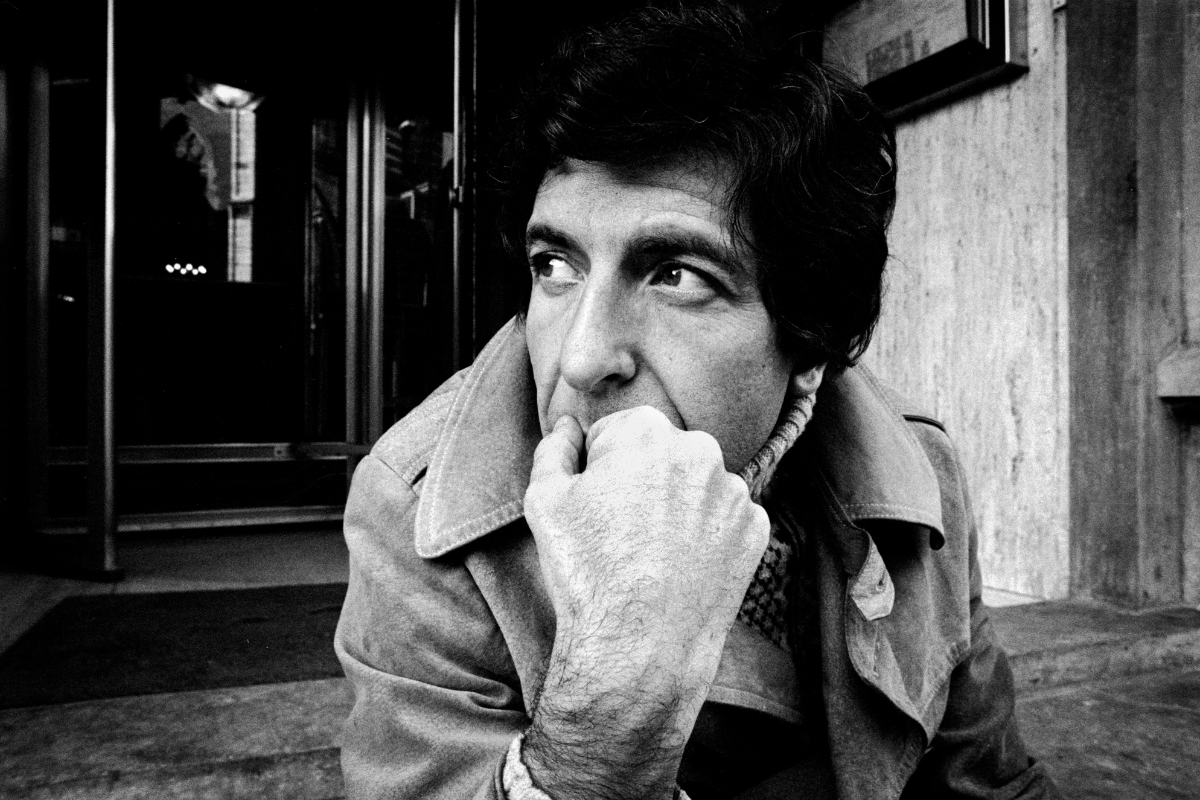

Max Layton, son of Canadian literary icon and close mentor of Leonard Cohen, Irving Layton, eulogized the Jewish musician as “the greatest psalmist since King David.” While Cohen indeed composed some of the most moving songs and poems ever written, he was no saint — in his own eyes or in the recollection of those who knew him best. Rather, he should perhaps be best remembered as, in the words of one of his young, female fans, a “beautiful creep.”

To refer to Cohen as a “beautiful creep” is not to insult his memory or tarnish his legacy, which is still strongly felt more than six years after his death in 2016. It is simply to look at the full record of Cohen’s life and consider the contradictions of a complex artistic personality who, above all, taught us that “there is a crack in everything… that’s how the light gets in.”

Shortly before releasing “Suzanne,” his first hit song in 1967, Cohen was a fledgling, experimental writer living in Montreal. His second novel, “Beautiful Losers,” published in 1966, is considered a classic of postmodern Canadian fiction — and also a book so grotesque and problematic that it can no longer be studied in many university classrooms. If its graphic depictions of masturbation do not make you want to vomit, I can assure you that its appropriative depictions of Indigenous women will. The current generation’s disgust with “Beautiful Losers” is not just hindsight; in the year it was published, it was reviewed as “the most revolting book ever written in Canada” (and also “the most interesting Canadian book of the year”) by the largest Canadian newspaper, the Toronto Star.

Similarly, it is not only in the wake of the #MeToo movement that elements of Cohen’s life and artistry come across as, for lack of a better term, super creepy. He was taken to task in a harsh review of his album “Death of a Ladies’ Man” in 1978 by Chateleine magazine, in a piece cleverly titled “Death of a Ladies’ Chavaunist.”

The review asks optimistically, “Could the plural ‘Ladies’ mean rejection of his former womanizing self?” Like much of Cohen’s work, the answer of the title song’s lyrics is full of poetic ambiguity:

He offered her an orgy in a many mirrored room

He promised her protection for the issue of her womb

She moved her body hard against a sharpened metal spoon

She stopped the bloody rituals of passage to the moon

And in the 1970s, as today, you cannot help but react with horror at the most disturbing poem in his literary canon, “the 15-year-old girls” published in his 1972 collection “The Energy of Slaves”:

the 15-year-old girls

I wanted when I was 15

I have them now

it is very pleasant

it is never too late

I advise you all

to become rich and famous

If only Cohen’s alarming interest in “15-year-old girls” was merely found in one poem. But the ugly truth is that Cohen’s attraction to young girls is a theme repeated throughout his life, such as the harrowing story of “hypnotizing” his family’s 15-year-old maid to undress (according to the author of Cohen’s epic three-volume oral history, Michael Posner, it is unclear exactly what Cohen’s romantic involvement with his maid entailed, and he expressed genuine regret for the whole episode later in his life). Most damningly, a 1971 interview with Rolling Stone magazine ends with a random Cohen outburst, “Hey, where are the 14-year-old girls? This is California, isn’t it? Where are the 14-year-old girls?” It is unclear from the interview if these words, like so much of Cohen’s work, were full of irony or meant to be taken seriously.

Posner, who interviewed hundreds of Cohen’s closest friends and associates, shares with me his judgment that “Cohen was not a predator like Harvey Weinstein, Roman Polansky or even his Zen Buddhist teacher and close confidant Joshu Sasaki.” Sasaki, whom Cohen served as his personal attendant for five years — and according to Posner, was the single most important relationship in Cohen’s life — was truly a sexual monster. According to Posner, Sasaki exploited Cohen’s fame to “attract women into the Zen center,” adding to his hundreds of abuse victims.

Cohen, according to Posner, was never accused of coercing women into sex. Rather, he “was a guy driven to a large extent by libido” who enjoyed the life of a touring musician and the ample number of “women who threw themselves at him, literally.” Some of these women he related to as muses who inspired some of his best songs, such as “So Long, Marianne.” He was never married, and the mother of his two children, Suzanne Elrod (in addition to some of his other long-term lovers and his children), has chosen to remain silent regarding her relationship with Cohen — leaving huge gaps in our knowledge of his life’s most intimate details.

It is understandable that some will choose to focus on the bright side of Cohen’s life, such as the unforgettable lyrics to “Dance Me to the End of Love,” inspired by the tragic march of Jews to their deaths during the Holocaust. Cohen allegedly wrote as many as 180 verses to perhaps his most famous tune, “Hallelujah,” a song that literally means “praise God” and whose deeper spiritual meanings will be debated for decades or centuries to come.

Others may never be able to see beyond the uglier details of Cohen’s life. For me, the intention of seeing Cohen as a “beautiful creep” who saw and accepted all of himself — his brilliance, his love of women and his darkness — is part of my own effort to see and accept my own dualities, as well as everyone else’s. As Cohen reflected in “You Want it Darker,” released only 17 days before his death, the story of being human is all too often about the tragic and paradoxical inability to live up to our divine nature:

Magnified, sanctified

Be the holy name

Vilified, crucified

In the human frame…

There’s a lover in the story

But the story’s still the same

There’s a lullaby for suffering

And a paradox to blame