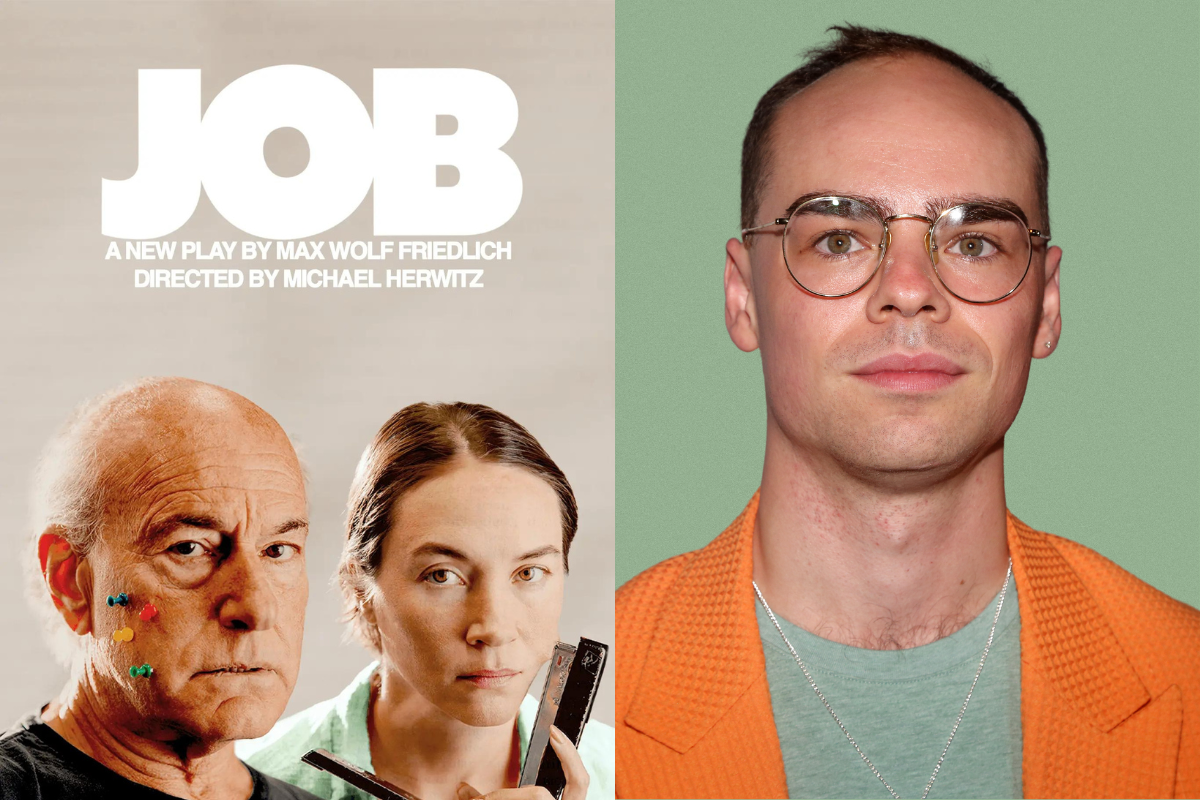

Few people have had a whirlwind year like Michael Herwitz. The 28-year-old queer Jewish director took a chance on directing a play his high school friend had written, not expecting the opportunity to turn into both his off-Broadway and Broadway debuts.

Herwitz, who directs Broadway’s latest smash hit “Job,” spent the early years of his directing career honing in on instilling Jewish magic in his work while working with the Jewish Theater Ensemble at Northwestern University.

“Job” focuses on Jane (Sydney Lemmon) who is forced to go to mandatory therapy sessions with Lloyd (Jewish “Succession” star Peter Friedman) after she has a public meltdown at her tech job that goes viral on social media. Throughout the one-act play, written by 29-year-old Jewish director Max Wolf Friedlich, the audience begins to see a deeper connection between patient and therapist, forcing them to question both characters and their intentions.

While “Job” does not have the overtly Jewish themes and storylines that many of the plays Herwitz was involved with in college did, after spending a year and a half working at Congregation Rodeph Shalom on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Herwitz learned a lot about rabbinical spirit and Jewish faith and community, integrating many of those elements into the way he directs his company.

The cast and crew of “Job” even said the Shehechiyanu over apples and honey on the first night of Rosh Hashanah when the play sold out within 24 hours during its first run at SoHo Playhouse.

Herwitz chatted with Hey Alma about his experience working on “Job,” making Jewish theater and his Jewish identity.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Just to kick things off, can you tell me a little bit about your Jewish identity and upbringing?

I spent the first 13 years of my life in Westchester County in a town called Irvington, which had a very sizable Jewish population.

I grew up in a Reform household, but I never had a bar mitzvah and had very minimal Hebrew school education, in part because I was a child actor. A lot of my time was spent auditioning and being in shows and that competed with the Sunday and Monday night Hebrew school schedule that my father wanted me to be on. So I would not say that I was raised with a strong connection to Judaism. I think that came much later.

And what was that like, to delve into your Jewish identity in adulthood?

Growing up, I don’t think I understood anything about Judaism in any kind of way that created a real sense of identity or meaning for me.

After I moved to New York City when I was 13, I began to understand what it meant to be ‘culturally Jewish.’ I was around so many Jewish New Yorkers and began to understand what Jewish humor meant, and the Borscht Belt-like sensibility that I feel is synonymous both with Manhattan and Larry David. The idea that Judaism wasn’t just something that happened in the synagogue, and it wasn’t just the thing we did when reading the Maxwell House Haggadahs at my aunt’s Seder table on Passover — that was only a sliver of what Judaism means to people.

I got to college, and one of the hallmarks of Northwestern’s theater program is this vibrant student theater community. There are 10 different organizations that are all run by students that produce three or four shows a year. One of those organizations is called the Jewish Theater Ensemble.

When I got to campus my freshman year, I had crushes on all the boys who were in the Jewish Theater Ensemble and I thought they did the best work on campus, so I ended up petitioning for JTE. By the time I was a senior, I was the artistic director of the Jewish Theater Ensemble, which was a real education, not only in theater, but in Judaism, and sort of figuring out where those two things meet. That is really where the corner turned for me.

How has the last year felt to you? You made your off-Broadway debut with “Job,” and now the show has moved on to Broadway.

I don’t think I know yet. It happened really fast. We did not start this play expecting that we would end up on Broadway. Some shows start off-Broadway, and they already have a pipeline built towards Broadway, and that was not the case for us.

It’s the fulfillment of this crazy childhood dream. And I think the only way I’ve been able to get through it is by trying to hold the two extremes at once, which honestly feels like a very Jewish thing. On one hand, I’m saying “this is a miracle,” and I really tried to instill in the company that we don’t have to pretend that this is chill, we should be nerds about this.

On the other hand, there’s this feeling of trying not to get lost in the pressure of it. Yes, the play is just two people in a room, but now the room is just a little bit bigger and on 44th Street.

Why did the play initially resonate with you? What made you decide that you wanted to work on it?

Max [Wolf Friedlich] is a very dear friend of mine, and I love him, and we’ve worked together on many plays, and so whatever it is that he hands me, I tend to say yes. Also, as a young director, you often don’t have a lot of choices to make because you just want to work. So I would be lying if I said that I sought him out.

I think “Job” speaks to the experience of a young person who went to a liberal arts college between 2010 and 2020, and digs into what it means to be a young person who spends a lot of time on the internet and has forged an identity around the internet.

The play has a reputation for being a thriller, but I would say the thing that I was most attracted to is its most tender quality. The two characters in this play are trying to do right by each other, despite all of their fear. My job as a director was not to lean into the thrill of it, because that was always going to be there, but rather to try to find where its heartbeat lay.

You and Max are longtime friends. What is it like working together, and how do you balance that work-friend relationship?

We get to fulfill this crazy fantasy together. We both know that we are young people who are learning a lot, very publicly, and neither of us has a ton of experience in this arena to back it up. We have helped each other just navigate the situation… because no one else really understands what’s happening.

It must have felt crazy that one day everything just lined up into place.

It’s also terrifying, you know. It’s the best, most privileged kind of growing pains.

Despite being a two-person cast and small crew, there are a lot of Jewish people involved with “Job.” Do you feel Jewish energy radiate through set?

I do feel it radiate through our company for sure.

One of my biggest directing inspirations is Rabbi Ben Spratt from Rodeph Shalom. The way that Ben speaks and gets everyone on the same team, to me, is so directorial. It’s very much the same job, rabbi and director. Our job is to stand in front of the room and tell everybody why this story is relevant and important and how to ground ourselves in something that feels both real and also a little bit mythical.

I’ve taken a lot of my cues from him. There are many times when I stand in front of the company and channel my inner rabbi, thinking what does this company need to hear to best commemorate this moment? And because our journey has been so unique and surprising, I’ve tried to build in time and space for us to celebrate things and to be like, “look at where we are.” A lot of that comes from a very rabbinic standpoint, and a very Jewish sensibility of marking time.

I just learned that, at one point, you thought you wanted to go to rabbinical school. What was the deal with that?

For both rabbis and directors, our job is to tell stories to help people make sense of the world around them. My mission as a theater artist is just to connect people to their emotionality; part of the reason I do theater is just to remind people of their capacity to feel something, be it theory, be it fear, be it pain, be it love, be it joy. I think that’s very true of why people go to synagogue, or why they turn to Judaism — it’s to feel connected to something bigger than yourself, to remind yourself that you belong to a history and a culture and that life is meant to be felt.

What do you want audience members to feel when they leave “Job”?

I actually don’t care, as long as they feel anything. People tend to leave the theater feeling really shaken. And that is sometimes hard for me to contend with.

I hope that the audience has a real ton of empathy for both characters. If they were holding any character in judgment, I hope that by the end, they are not holding that judgment anymore.

And I sort of hope that they see themselves in the story somewhere, especially young people. That feeling of connection might scare you as an audience member thinking “I don’t want to see myself in that story,” but I hope that you do, and I hope that that allows you to walk through the world a little more sensitive and a little more sentient, even for a couple of hours.

“Job” has a limited run. Do you have any projects lined up afterward?

I’m actually going back to where I went to high school, LaGuardia High School, in the fall to direct “Into the Woods.” It’s a very funny change going from Broadway to my high school’s play, but I’m really excited about that. It’s gonna be a really needed change of pace. I can’t wait.