When I was 9 years old, my brother got a tattoo.

I didn’t understand why everyone was so upset or why people at my small-town Texas synagogue were talking about it. I thought it was SO cool — a permanent sticker on your body? Sign. Me. UP! And so, on one fateful Sunday during free time at Hebrew school, 9-year-old me drew my dream tattoo: a soccer ball with a Star of David in the middle (it was truly a work of art). Naturally, my moreh (Hebrew for male teacher) wanted to know what inspired this awesome drawing, and so I told him: one day I would get that soccer ball tattooed on my shoulder, just like my brother got his tattoo.

This was… a problem.

The next Sunday, our teacher planned a whole lesson for us about our bodies in relation to Judaism. He started by telling us that we were all made b’tzelem elohim, in God’s image, like everything else that was on the planet. He said that each and every one of us was so important to God — that God had spent time crafting us, making us unique and beautiful in our own way, and then sent us out into the world.

Like many Jews, I was born with anxiety and endless questions. I was the kid in Hebrew school who was trying to understand everything, constantly raising my hand to dig deeper into each class’ lesson — much to the annoyance of my classmates and teachers. I now find Judaism’s gray areas beautiful, but they used to irk me and keep me up at night. So I would try to search, usually in vain, for concrete answers. Growing up in a family that moved homes at least once a year, I found the stability I longed for as a little kid in that kind of Jewish halacha. Kosher laws, for example, were a great start— there were clear yeses and nos, criteria for what made food permissible or impermissible to eat.

This — b’tzelem elohim — was also concrete. There was no debate that we were made in God’s image. We all felt special — honored, even, to have been chosen to live out such a holy and gorgeous experience.

But that special feeling turned into fear when I learned that b’tzelem elohim, a line from Bereshit 9:6, also meant I was God’s property.

Wait, what?

My teacher taught a class of 9-year-olds that our bodies were a lifetime loan from God — that we were borrowing them while on this earth and that they weren’t really ours to do with what we wanted. This was supported by another beautiful concept from Devarim 4:9 called sh’mirat ha-guf, the teaching that we are meant to protect our bodies because they are beautiful creations. Through the medieval Torah sages’ interpretations, we are meant to guard them not necessarily because they house our lives, but because they are loans from God. And, since it would be disrespectful to damage or change somebody else’s property without their approval, that meant no tattoos.

This was indisputable. The question portion of class was replaced with extra time to be outside since it was Tu Bishvat that week.

My tattoo phase turned out to be temporary (yes, I do crack myself up), but my anxiety around my borrowed body was not. Was God upset that I had scraped my knees last week? Or that I had accidentally hurt my friend in P.E. a few days ago? That I just accidentally stepped on an ant? There was so much harm that I was committing against God’s creations, and I hadn’t even realized. Was I the worst person in the world?

As I got older, these feelings became more complicated. What would God think if I kissed someone, or if I wanted to pierce my nose (which I later found out is technically halachically permissible and ran with)?

I was terrified of my body, of having a body and of being around other bodies. By the time I got to high school, I felt completely separate from my body. I told myself this was all cool cool cool.

But it wasn’t.

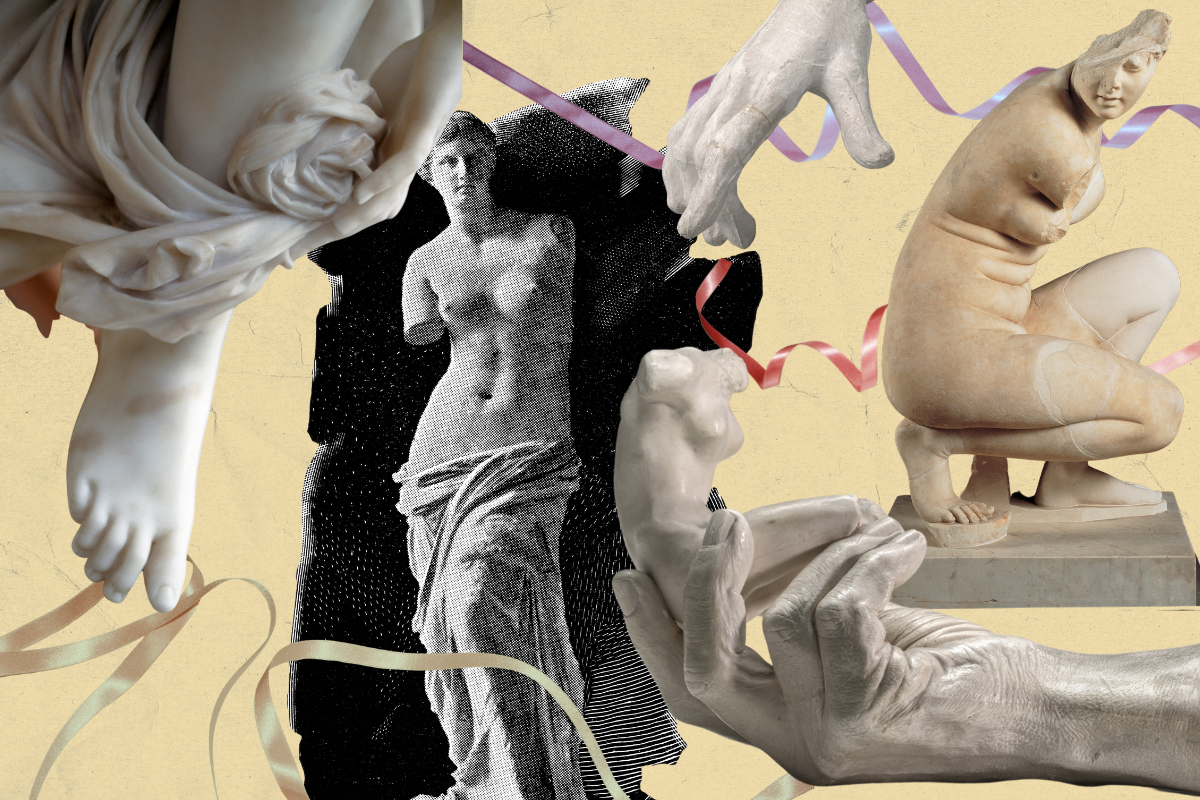

I began reading about the concept of bodily autonomy in Judaism and comparing it to the way that other cultures and religions discuss the body. I learned about the sacred nature that tattoos take on in Polynesian culture, theories of reincarnation in Hinduism and many other South Asian cultures, and the desexualization of the body in certain South American Indigenous cultures like the Pirahã and so on. What I found is that there are endless forms of human conceptualization of the body’s role in our life.

So I began to question again, and came to my own interpretation about why we have bodies:

Our bodies are vessels for joy. If we have the ability to, we take in beautiful views with our eyes, listen to incredible sounds with our ears and taste delicious foods with our tongues. We embrace each other, and feel love and comfort. We live in our bodies. As the great Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandra once said, “The body is the soul’s house.” Don’t I deserve to feel safe and comfortable in my home? To enjoy my home? To not be scared of my body?

A loan is not enjoyed. A loan looms in your mind, reminding you that what you owe must be paid back in time or there will be consequences. A gift is enjoyed.

My body is a gift from God, not a loan.

My body is meant to be enjoyed. It’s the greatest gift that I’ll ever receive in my life because it gives me life. If there is a God, it would be disrespectful not to use this creation to its fullest potential.

Had I been taught that my body is a gift, I would have avoided years of fear. I would have come into myself sooner and been more confident in my own skin. By perpetuating the language which states that our bodies are loans, we perpetuate bodily anxiety and shame. So I will never again tell a Jewish child, or any child, that their body is a loan, but remind them that it is a beautiful and invaluable gift for which they should care. I hope that you’ll do the same.