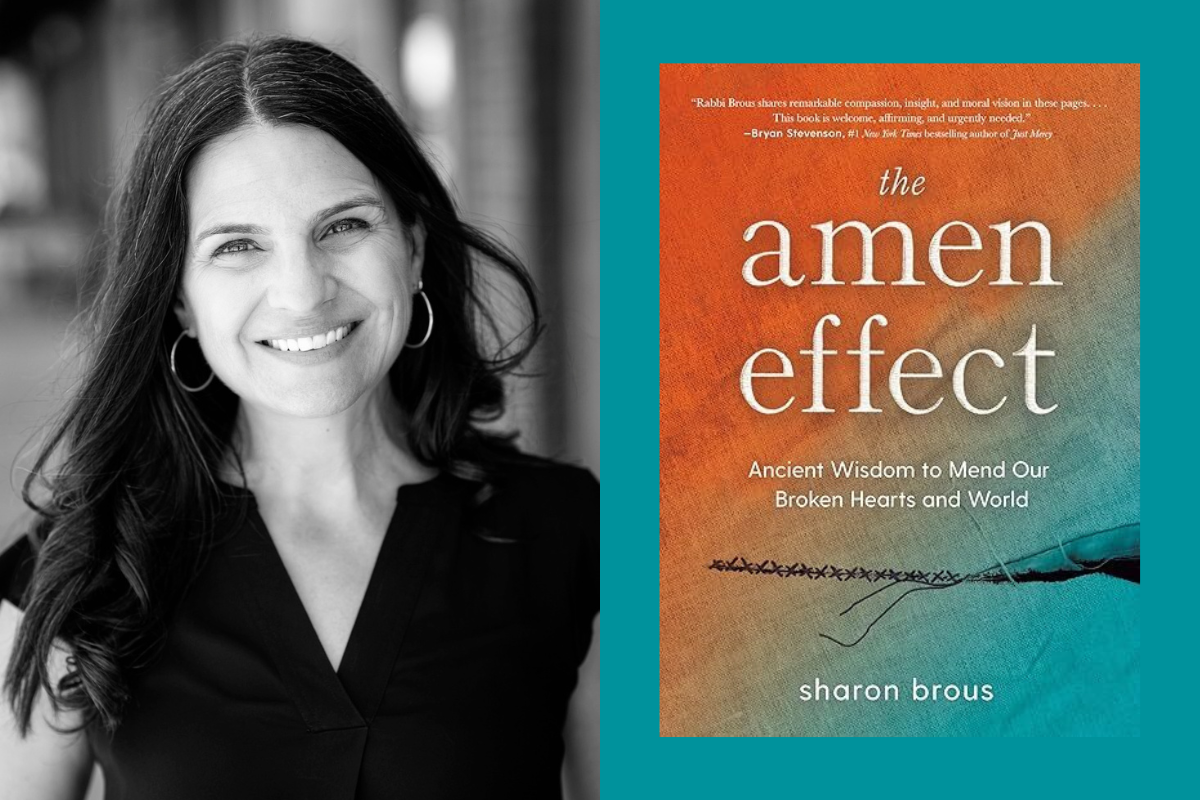

Once a book actually makes it out into the world, you can bet it’s been in development for years beforehand. It takes a long time for a writer to dream up an idea, write it all down and then work with a publishing team to edit it, print it, market it and get it into the readers’ hands. With this in mind, it’s incredible that “The Amen Effect: Ancient Wisdom to Mend Our Broken Hearts and World” by Rabbi Sharon Brous, published this past January — exactly when we all needed it most.

You’ve probably heard of Rabbi Brous; if there’s such a thing as a “celebrity rabbi,” she certainly fits the bill. She is the founding and senior rabbi of IKAR, a trailblazing Jewish community in Los Angeles, she has been named the #1 most influential rabbi in the U.S. by The Daily Beast, she blessed both President Obama and President Biden at their Inaugural Prayer Services and her sermons frequently go viral. She’s also very compassionate, very passionate and very dedicated to the effort she outlines in her book: mending our broken hearts and the world.

Hey Alma met with Rabbi Brous over Zoom earlier this month to discuss her new book, how to connect with Jewish community, the importance of having difficult conversations with people we love (and people we don’t) and what this particular moment in history demands of us as Jews.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

In “The Amen Effect” you write that the Torah tells us twice that being alone is not good. Many of our readers do not feel connected to a Jewish community. What are some concrete things they can do to be less alone in their Judaism (and their lives) especially if they feel weary of joining in more organized/traditional institutions for whatever reason?

The wisdom of the Torah absolutely stands that it’s not good for a person to be alone in the world. And that doesn’t mean you should go get married — it means we have to find our people. We have to find people who see the world in a way that helps us feel seen, and helps us feel less alone. And those people do exist in the world, it’s just not necessarily going to be reflected in the pages of our press, it’s not necessarily going to be reflected on social media.

And so the question is, can we trust that there are others who are holding complex realities like we are, and in whom we can take comfort by seeing them and being seen by them? I see this as both a moral and spiritual imperative in our time.

There are ways to root ourselves in [our] communities, it just requires more of an effort. It requires us investigating, interrogating, finding and even creating communities where we can be held tenderly and held with love.

That can be a book group. That can be a group of folks who come over just for Shabbat dinner once a month to your house. That can be a synagogue if you find your right synagogue. It doesn’t have to be [any of those specific examples], but we have to root ourselves in those kinds of communities.

In the final chapter of your book, you ask us to consider what happens when we find ourselves in community with another person who “not only repels us, but renders us unsafe?” It feels like at this moment in history, many people in the Jewish community feel that way about each other, even if it’s not true. How can we make connections with fellow Jews when we disagree so vehemently?

The central paradigm of my book is this ancient pilgrimage ritual, when Jews would come from all across the land and from the diaspora [to] Jerusalem. They would ascend the steps of the Temple Mount; they would enter through this giant, beautiful entryway and turn to the right, and circle around the perimeter of the courtyard of the Temple Mount and then essentially exit [just where they came in].

Except, the text says, for someone with a broken heart. That person would go up to Jerusalem, would go up the steps, would turn to the left and circle in the opposite direction from everyone. And the people who are coming from the right, when they would encounter someone from the left, would have to see them, see their humanity, see their brokenness and ask a simple question: What happened to you? What’s your story? Why does your heart hurt? What does the world look like from your perspective?

And then this person would answer saying, “My father just died and I’m upside down.” Or someone else might say, “I found a lump and I’m terrified.” And then the people who are going to the right would answer with a blessing: “May you be held with love as you navigate this treacherous time in your life.” And then they’d all go on.

The power of the ritual is that none of these parties actually want to be engaged in this ritual. All of them instinctively want to retreat from each other. There’s so much power in the sacred encounter that draws us to each other at precisely the moment when we want to retreat from each other.

The Mishnah says that it’s not only the brokenhearted who are turning to the left, but also the ostracized — the menudah. These are people who have caused harm to the community. It was a very rare, very severe punishment. And yet, on the pilgrimage days, they also show up. And when we’re going to the right, and we pass someone who’s coming from the left who’s ostracized, we look them in the eyes too, and we say to them, “Hey, what does the world look like from your vantage point? Tell me about your broken heart.” We approach them with curiosity and with wonder. And they respond by telling us that they are among the people who have caused us grave pain. And we don’t walk away. We don’t turn our backs on them. We still bless them, that we might find a way to be back in community with them somehow. And then we keep going. And I’m astonished by this.

To the point of safety, there are people in the category below the menudah, you know, one step worse than the ostracized, and they are not allowed in that courtyard at all, because their presence there would render us unsafe. They are not open to having this kind of connection, this kind of awakening to the humanity of the other. But almost everybody else, including the ostracized, including someone who’s caused grave harm, almost everybody else is in that space together, and they see each other.

The reason I’m taking the time to articulate this is because I am not suggesting that every single person can be reached. I don’t think that it’s the work of impacted communities to endanger our own lives to reach people and help them understand us. But I do believe that most people can be reached. It might be uncomfortable for us to connect, but it will not be unsafe for us to connect. And part of what we have to gauge is — is this unsafe, or is this uncomfortable? If it’s unsafe, don’t do it. If it’s uncomfortable, if you have the bandwidth for it, you gotta do it.

Could we engage them with enough of an open heart that we make space to learn about where their sorrow is coming from? Because I think when we meet sorrow with sorrow, we meet vulnerability. With vulnerability, we’re able to move beyond some of those obstacles to actually connect. It doesn’t solve everything, but it begins a conversation that can help us rehumanize each other.

Since October 7, some Jewish leaders have called to cast out Jews that don’t agree with them from our religion. I’d love to hear your thoughts on that, and perhaps some wisdom about how Jews who have heard these calls and feel deeply hurt by them can move forward in forgiveness and the knowledge that they are Jewish enough.

I get interviewed a lot by people who ask me to condemn other Jews and the way that they’re responding to [this moment]. And sometimes I am really hurt by the positions that others in the Jewish community are taking on, but I will not engage in that kind of public shaming of other Jews, because I feel like we’re all responding from sorrow. And we’re all trying to figure out how to hold a truly excruciating and impossible reality right now, and I understand that there are really good people who come to really different conclusions about how best to do that.

Even as I often see people who are engaging in ways that I find — both on the anti-Zionist and on the Zionist side — are really harming our discourse, I try to take it in as an expression of grief, an expression of anguish and an expression of their Jewish values. And so even though I’m sometimes very worried about what I’m seeing in the discourse, and I often think, God, there are better ways for us to be talking about this, rather than shaming and blaming… I try to understand when I’m engaging someone who comes from one of these perspectives, or the other, that they’re brokenhearted, and they’re trying to figure it out. It is not easy. And I think anyone who thinks that this is easy and simple and uncomplicated is not being honest about what’s really at stake here.

What I’m advocating for is a much more human engagement, where people who don’t see things exactly the same can sit together and share from their heart without feeling like they’re traitors, like they’re betraying their people. And that is really hard to do on social media. And that’s really hard to do at protests and counter protests. That kind of rehumanizing engagement, I’ve found, can really happen only in quieter, more intimate spaces, where we’re able to sit together and see each other, and hear each other and actually engage in the work of finding our way to each other.

And I’ll just say one last thing about this, which is, for the last four and a half months, I’ve been thinking about Venn diagrams. I’m thinking in circles all the time, because the central paradigm of the book is circles, but these are not concentric circles, this is about overlapping circles. And I think in the Venn diagram of the Jewish community, we often find ourselves screaming at each other from the margins, from the outer edge of these two circles. And in fact, there’s a lot of overlap. And that overlap is often in the place of anguish, sorrow and grief. It’s often in the place of trauma, it’s often in the place of fear for the future. And it’s in the place of core values that we hold as Jews. And yet, we don’t see that in each other.

When someone who has disavowed Zionism engages with someone who still holds a deep attachment to Israel as a state and an idea, they don’t often see: Here’s what we share. They’ll often end up seeing: Here’s where your view is endangering my life. And that is not the place to find one another. So what I’m asking for is a kind of quieter, more human engagement with each other, where we can actually see the places where we can meet, where we can share understanding of the treacherousness and also the possibility of this moment.

For the people who are wanting to find that inner Venn diagram space, what does this moment demand of us? What are the tangible things we can be doing to rehumanize ourselves and each other?

Beautiful question. And here, I’m just going to take us back to this — the idea that nobody in that encounter [during the ancient ritual at the Temple Mount] wants to be there. The brokenhearted doesn’t want to be there, the community of people who are OK don’t want to be there. And yet, that’s exactly what our Jewish tradition calls us to.

You don’t want to show up at shiva, you’re busy, you have work to do, and you don’t want to encounter someone else’s brokenheartedness, because it reminds you that you too, could be brokenhearted. And yet you go to the shiva, you go to the funeral.

So what I would say is take that same model of active spiritual discomfort and apply that to this moment and say: Who are the people who I love and care about, but who I can’t bear to sit down with right now? Because they’re breaking my damn heart? And how can I step closer to them when I want to retreat from them? And to see that as a spiritual imperative, and a moral imperative. Because otherwise, it’s breaking our families. It’s breaking our community. And I think it’s gonna break our democracy.

Do you have any concrete tips for people looking to have those conversations?

I’ve noticed that I need to notice what’s going on in my body. When I’m feeling attacked, and I get hot and red and I feel this fight or flight instinct — I want to pay attention to that and say, okay, how can I create enough distance that I feel safe in this conversation so that I can get curious again?

I think the rule is deescalation and curiosity. And you have to deescalate in whatever kind of ritual [works for you]: Is it breathing? Is it imagining a screen coming down? Is it taking a physical step backwards? Is it closing your computer and coming back an hour later after going for a walk outside? There are techniques that we can use that then help us approach [each other] with wonder.

The courageous move right now, the imperative, is to step toward each other instead of retreating. And that means calling your person who you’ve been avoiding, and saying, “Hey, can we have a real conversation? I want to talk to you.”

Not all of these conversations are gonna go well. I’ve had a few that have really not gone well in the last couple of months. Some people on the receiving end are like, I don’t want to get to that center overlap in your Venn diagram, I want to scream from out here. And those people can’t be touched, but then maybe the next person can. As I write about in the book, for every one you can’t reach, there’s someone who you can. And I think that the exercise of trying to reach each other not only gives the potential of rehumanizing the other, but actually reminds us that we have agency, that we are not powerless in this moment, that there’s something that we can do. And that requires stepping out of our ideological bubbles and being a little bit uncomfortable, and being willing to hear people who express views that are antithetical to the views that we hold.

I do have boundaries. I’m not going to engage in a conversation with a rape denialist, just as I wouldn’t engage with a Holocaust denier or Sandy Hook denier. That’s a conversation that I know that I cannot have and I won’t have. But short of that, I’ll engage pretty much anyone else. I’m willing to be uncomfortable, but I’m not willing to be clobbered so that I can’t do my work.

So I think we all have to gauge: Where do we feel we can go that will stretch us and not break us? And then we have to go there.