Content warning: suicide

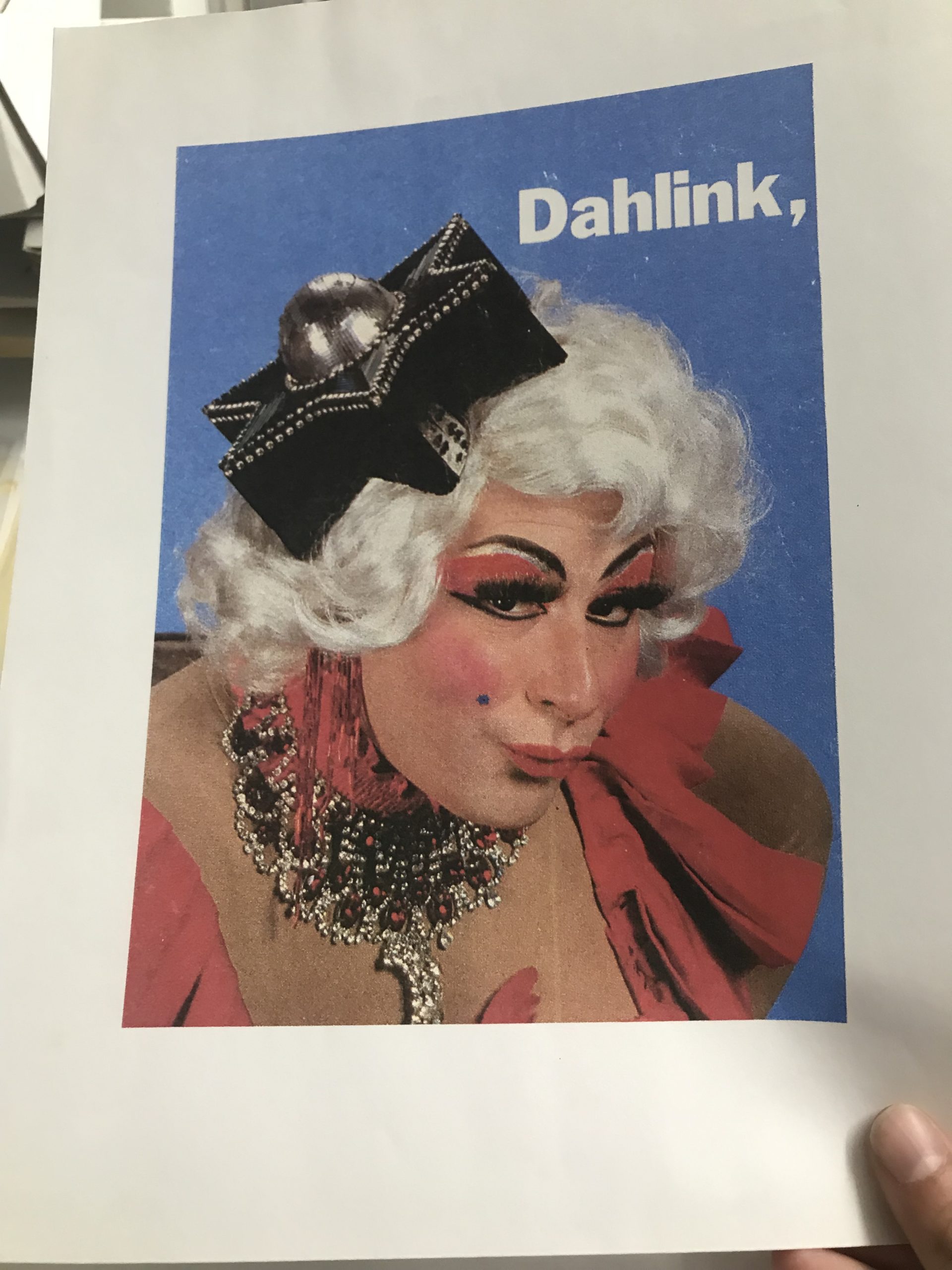

The first thing I noticed was a glimmer of rhinestone. I gasped as I gently pulled back the clouds of tissue paper. Nestled within was an all-black, Star of David-shaped hat complete with a tiny disco ball positioned in the center and a miniature Torah attached artfully to one side. I had seen this hat, called a “Synagogo” hat by its creator, in photographs before, but in person it was like greeting the ghost of an old, dear friend: at once deeply nostalgic, a little magical and definitely subversive.

Handling the Synagogo hat was one of my duties a couple summers ago, as an intern at the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. I was working on the Sadie, Sadie the Rabbi Lady/Gilbert Block Personal Papers. Gilbert Block, also known as Sadie, Sadie the Rabbi Lady, was a gay Jewish drag queen and one of the founders of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an order of queer nuns who engage in guerrilla theater, activism, and perform rituals from Pagan, Christian and Jewish traditions while satirizing the Church.

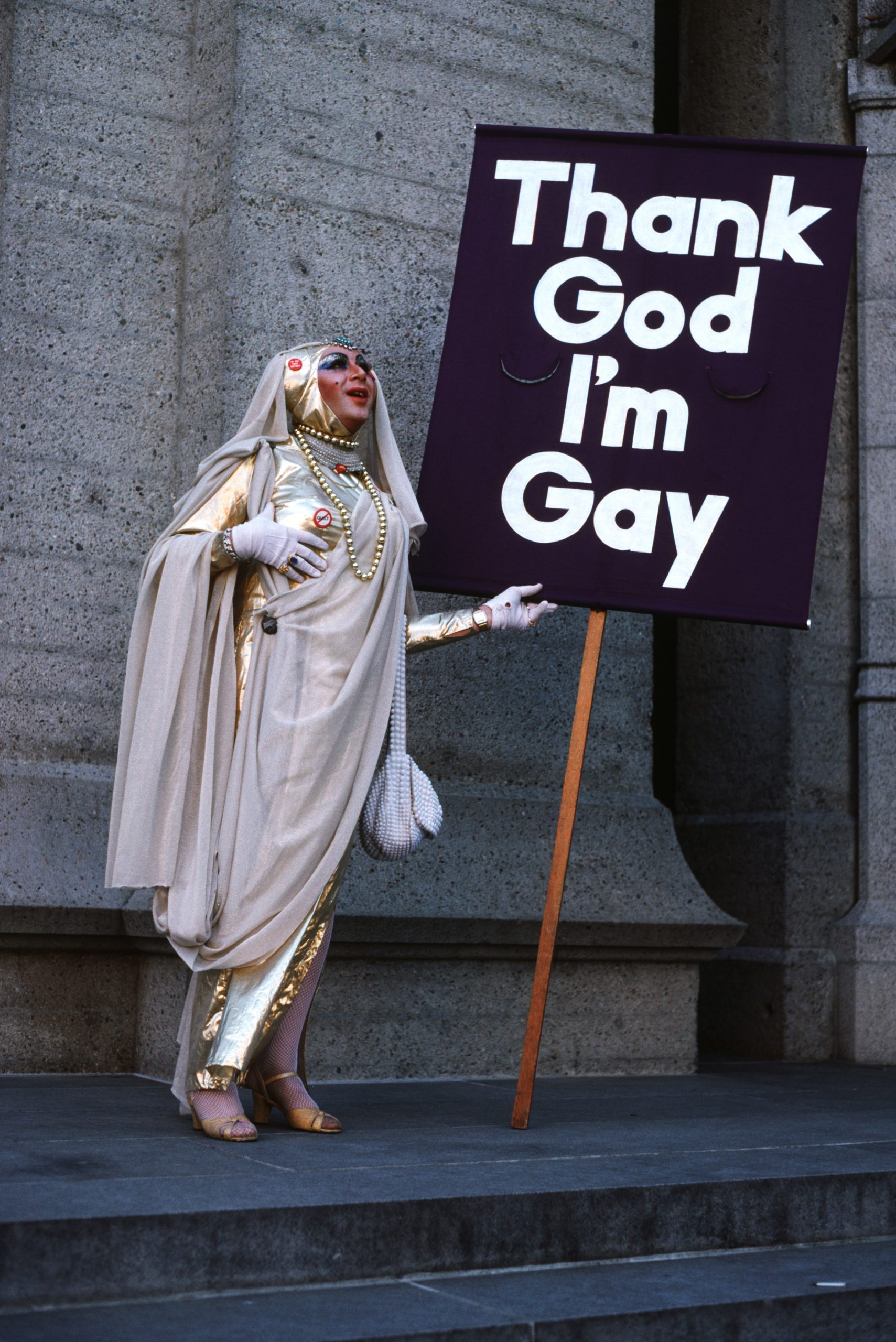

Block was born in 1944 to a Jewish family in the United States, but spent formative years of his childhood in Canada before moving to San Francisco. When Block joined the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, Sadie, Sadie the Rabbi Lady was born. Block describes Sadie Sadie as being inspired by a number of famous actresses and “everyone’s favorite Jewish grandma from Miami.” Sadie, Sadie the Rabbi Lady also joined organizations such as QueerNation and ACT UP, protested against environmental devastation, performed a cabaret show about safer sex, and of course, attended many glamorous parties.

A large part of my internship involved learning how to do archival “processing,” or organizing a collection for researchers to access and caring for materials to help them last longer. In my case, this included making decisions about how many duplicate pamphlets — specifically about how to have safe sex, created at the beginning of the AIDS crises — should be retained. It was also part of this process during which I created a special box to keep rhinestones on the Synagogo hat safe for posterity.

A friend of mine calls archiving “live-editing history,” and it can be a surprisingly intimate experience. I gasped at glamorous, and slightly scandalous, photoshoots of Sadie Sadie posing in front of a local synagogue in gorgeous, flowing gowns. And I read, and smoothed out, dozens of clippings written by or about Sadie Sadie, including many about an event hir and fellow drag queen Sister Chanel hosted during the Pope’s offical visit to San Francisco in 1987, in which they were arrested for protesting the Catholic Church’s stance on abortion, among other issues. I found news articles in which Jewish grandmother Holocaust survivors were described as comparing fake gold bracelets with Sadie Sadie at protests they attended together. It was also part of this process during which I created a special box to keep rhinestones on the Synagogo hat safe for posterity.

Some of the decisions I made about what to keep in the collection felt personal: What am I supposed to make of the booklets of homophobic rhetoric that Sadie Sadie held onto? Were they accidentally included in the donation, or did Sadie Sadie intend for researchers to read about the homophobia hir survived?

As I was processing the collection, I was also processing the fact that Sadie Sadie the Rabbi Lady was out in the world being an openly queer Jew long before I was born, and that queer Jews were not, in fact, a new concept.

Gilbert Block sadly died by suicide in 2010 at the age of 66, five years before I was able to openly articulate what we might’ve had in common when I was an awkward high schooler. Growing up queer and Jewish in a small town, I had no chance to hear about people like Sadie Sadie, of people who lived as loudly and fully as they could. I like to imagine that Sadie Sadie gifted hir story as a kind of message in the bottle that hir knew I and so many other queer Jews would someday need, and was caring for us by sharing hir story. For me, being at the GLBT Historical Society Archives, where everything was for and by the represented community, gave me a powerful hope. Sadie Sadie’s collection allowed me to see hir vision of a better future, and in turn imagine my own.

Something about knowing Sadie Sadie existed gave me permission to explore myself. That summer, I attended the Dyke March, queer-themed Shabbat events, LGBTQ+ Jewish exhibits, and met other queer Jews. Once I saw — and held in my own hands — evidence of someone like me existing before, I knew the spaces I dreamed about could and did exist.

It was the privilege of a lifetime to be allowed to hold a piece of Sadie Sadie’s sequined outfit, taking in the Jewish stars, magic and glitter, and to know tangibly that there were queer Jews before me. It also instilled in me my responsibility to honor Sadie Sadie’s vision, and to make sure that life is better for all of queer Jews who come after. I’m grateful to the archivists and community members at the Society who taught me important lessons in how to care for our history. And I’m grateful to Sadie, Sadie the Rabbi Lady, who in donating hir collection, has taught others about the importance of unfiltered, honest truthfulness to living a very fully, queer Jewish, life.