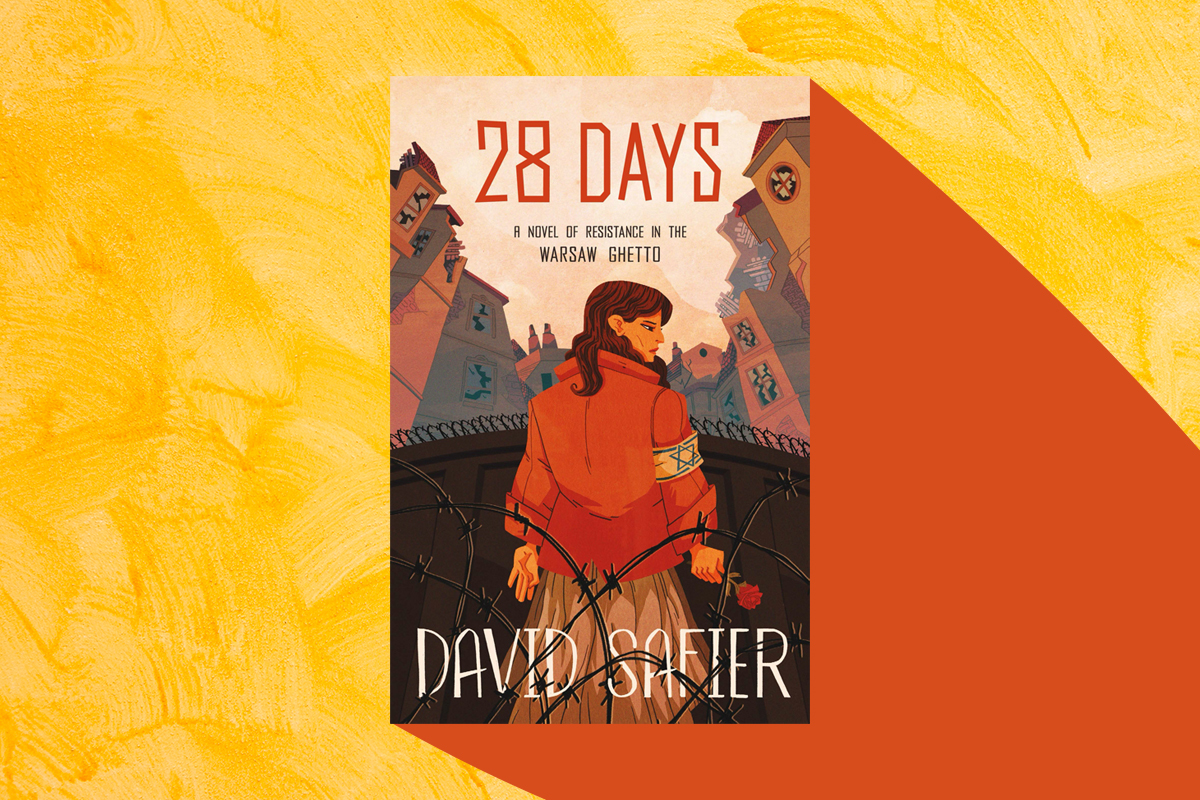

Right at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, an imprint of Macmillan published the English language translation of David Safier’s German YA novel 28 Tage lang, or 28 Days. The book is set in the months leading up to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, and at the height of the pandemic, it was exactly what I was craving: a story of Jewish resilience.

But I quickly realized that a story of resilience would not be enough. According to the Young Adult Library Services Association, the genre of young adult fiction has a responsibility to not only entertain, but to educate and support readers’ development of empathy, imagination, and literacy. When it comes to young adult fiction set during the Holocaust, this mandate becomes increasingly imperative: Young readers (both Jewish and non-Jewish) have the opportunity to understand the complexities of atrocity and examine the connections to the urgent social issues in their own communities now.

I found that while 28 Days is written by a Jewish author and set during a distinctly Jewish part of history, Safier’s choices in storytelling and character development stepped around or avoided the Jewish lens that I had hoped for.

28 Days joins the company of other YA novels about teen resistors in World War II, such as Shadow on the Mountain and Carla Jablonski’s Resistance, but it is unique in that its protagonist and narrator, Mira, is Jewish. Mira’s character evolves dramatically from a girl who is exclusively focused on providing for her family to an insurgent who is prepared to die for the resistance. Her transformation from a typical survivor to a resistance fighter serves as a compelling arc for a young reader who might be wondering what their place is in their modern Jewish community and political moment.

And yet, Mira’s Jewish identity is always at arms’ length, based in the othering she experiences under occupation rather than practice, belief, language, or an affinity for her own heritage.

We meet Mira as she is almost caught outside of the ghetto smuggling food for her family. I was struck by Mira’s gritty, jaded voice. She is 16 years old and lives in a bitter reality that has little room for hope. Readers are introduced to Mira as she engages in the unique act of passing as a Pole. Safier captures the tightly-wound high-wire performance in which the slightest sign of fear would give Mira away. Although she has some stereotypically non-Jewish features, her greatest asset in passing is her confidence and cavalier attitude as she scoffs at the Poles who threaten to turn her in, bluffing that she will be the one to go to the police over their harassment.

Safier immediately reeled me in with this scene. As someone who has spent hours upon hours in the archives studying the Polish-passing women and girl couriers of Jewish resistance movements, I knew that this was not an uncommon scenario for those who lived on both sides of the ghetto walls. These women and girls used creative tactics such as flirtation, strategic props (such as Havka Folman’s copy of Proust), or subtly elegant clothes to ward off suspicion. But their most important tool was their ability to smile and hide the signs of emotional trauma that non-Jews could distinguish in their Jewish neighbors.

Interestingly, in that first scene, Mira is rescued by Amos, a bystander who turns out to be another passing Jew. Amos is one of the leaders of Hashomer Hatzair (a Socialist-Zionist Jewish youth movement based in Eastern Europe, and a member of the coalition of the Jewish Fighting Organization), who later convinces her to join. The two of them eventually serve as liaisons for the movement with the Polish Home Army outside of the ghetto.

What makes this worthy of an eyebrow raise is that boys and men were often unlikely to be chosen to leave the ghetto in these roles because a) their circumcisions made them much more easily identifiable as Jews, and b) they were less likely than their female peers to have attended Polish primary and secondary schools, and thus were more likely to speak Polish with an accent or be less accustomed to subtle cultural cues. Men like Amos existed, but his central position in the story as a main character and love interest represents a very specific choice of Safier’s that stood out to me. It felt like Mira’s character needed a new comrade-boyfriend, and so one was contrived for her while the nuances of courier work were flattened.

In fact, there were other perplexing and seemingly ahistorical choices in the narrative that caused me to pause or reread a sentence multiple times.

For example, during the ghetto deportations in 1942, Mira and her family are spared while her Orthodox relatives from Krakow are deported to Treblinka. Mira scavenges the abandoned apartment and finds food that will sustain her mother and sister as they continue to hide — including ham. Later, in the weeks leading up to the Ghetto Uprising, Mira is given the mission of liaising with the Polish Home Army on the other side of the wall to acquire weapons for the Jewish Fighting Organization; in their Polish apartment, her comrade and love interest Amos whips up a breakfast that includes bacon.

You see where I am going with this.

Eating treyf (non-kosher food) alone is not what is questionable; it is the fact that the treyf occurs without context.

In times of starvation, Jews throughout the ages have been forced to forgo the laws of kashrut in order to survive (and often with great debate). The halachic (relating to Jewish law) principle of pikuach nefesh (the mandate to preserve life) allows for these exceptions. It’s also possible that Mira’s assimilated family did not keep kosher to begin with, and that eating ham and bacon was already acceptable to them. However, Mira is the young reader’s tour guide through atrocity. She does not remark as to how dehumanizing it must have been for her relatives to be forced to eat ham. For a YA audience, this feels like a missed opportunity to add an additional layer to Mira’s understanding of what it meant to be Jewish under Nazi occupation.

Similarly, Mira only references the Yiddish language once in the entire book. Mira speaks Polish, which allows her to pass as an ethnic Pole with greater ease. This on its own makes sense, as it is clear that her family is assimilated — her doctor father was most likely educated abroad, and she probably attended Polish schools before the war. The character has a very limited Jewish education and did not participate in Jewish cultural life before the war. However, it is highly unlikely that she had no connection to the Yiddish language.

The Warsaw Ghetto was characterized by its overcrowded quartering, which housed hundreds of thousands of Jews from all corners of Nazi-occupied territories — most of whom spoke various dialects of Yiddish. Mira would have been exposed to an immense diversity of Jewish experience in her new community. Because of this omission, we don’t get to learn that passing Yiddish-speakers were able to use this skill to their advantage as they could surreptitiously understand the conversations of German SS officers, as German is an almost mutually-intelligible language.

It is neither possible nor useful to say whether or not Mira’s background or character development accurately represents Jewish life in the Warsaw Ghetto, so I won’t try. I’ll just say that I was disappointed at this exclusion, not just because I have pride in the Yiddish language, but because it felt like another missed educational opportunity for young readers.

I struggled to contextualize Safier’s choices in the historical record, and instead looked to our contemporary moment. The original 2014 German edition of 28 Tage lang was published alongside some of the most intense points of the Syrian refugee crisis. I can imagine that the national conversations about Germany’s role in receiving migrants as they fled the Syrian Civil War were on Safier’s mind. Far right extremism was resurging in Germany, and in 2014 the National Democratic Party of Germany (a neo-Nazi group) won their first ever seat in the European Parliament. The urgency of Mira’s story of anti-fascist resistance was as urgent at that time for German youth as it is now for American youth.

As a cosmopolitan and assimilated young person, Mira serves to remind young German readers that you, too, could become refugees — or, on the flip side, that refugees are just like you. But did her universal relatability come at the expense of a more distinctly Jewish character?

28 Days is an exciting account of how a group of young people fought back against the Nazis. The energy and idealism of the youth fighters is infectious. Given that the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was led by youth and young adults, it only makes sense that young readers should have young protagonists to relate to when learning about this historic moment. This is a story about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, but it’s not necessarily a Jewish one.

28 Days is only one book, and it can’t be everything. There is so much radical potential in the genre of YA historical fiction. And we still need more. We need more Jewish stories. We need more stories with Jewish girl protagonists. We need more Jewish stories of resistance and justice, stories that seek to draw readers into historic moments with nuance and integrity.