Editor’s note April 2025: We have updated the byline of this piece to reflect the name that this author publishes under as of 2025.

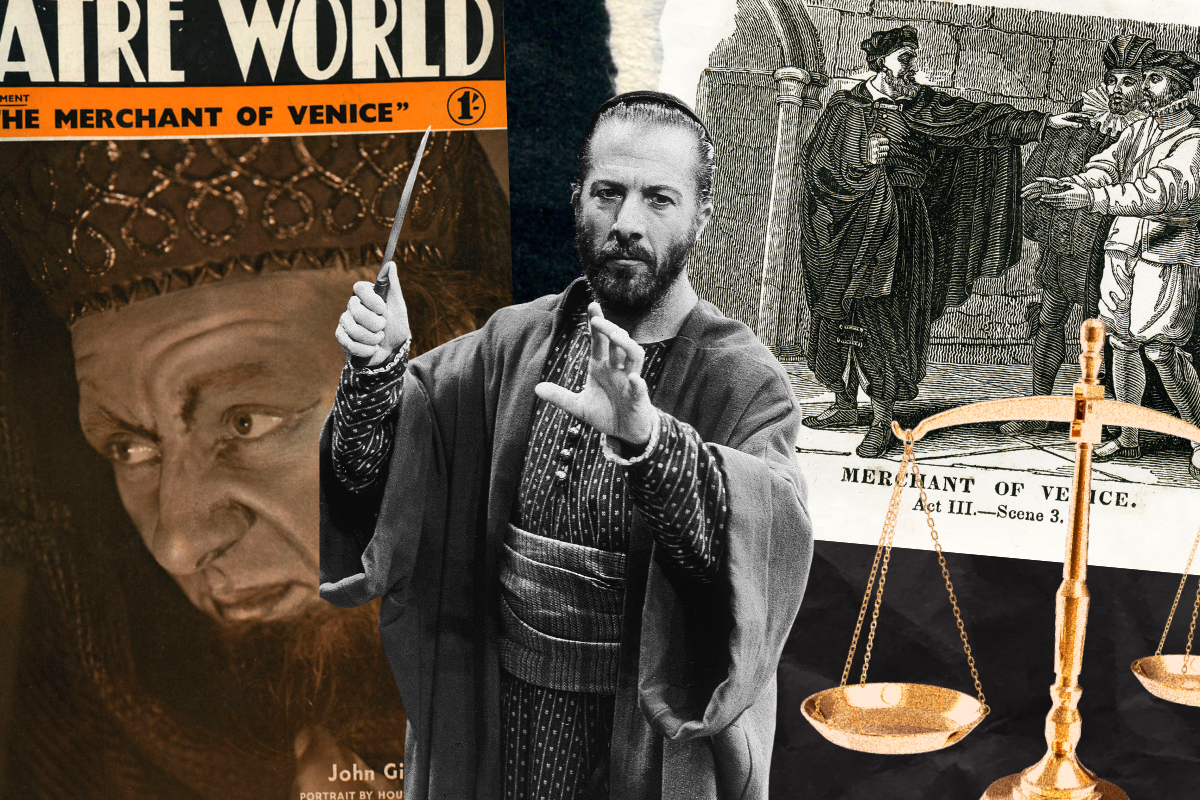

On March 6, Hannah Davis published a thoughtful piece on Hey Alma on Criterion Theatre’s misguided production of “The Merchant of Venice,” set in 1936. Her description communicated just how baffling the direction for this show was. It’s understandable, then, even inevitable, that Davis walked out afterward with the conviction that, “‘The Merchant of Venice’ simply cannot be a viable vessel for this [anti-fascist] message, because it is impossible to make such an antisemitic text into an empowering performance. It was doomed to fail from the opening line.”

Respectfully, and I hope reassuringly, I have to unequivocally disagree with this conclusion. Not only is it entirely possible to ethically stage a production of “Merchant,” but it has been done multiple times… which only makes the Criterion’s iteration all the more objectionable.

The best Bard that I have ever seen was the all-female (“LadyShakes”) production of “The Merchant of Venice” staged at the Shakespeare Tavern in Atlanta in August of 2022. The Atlanta Shakespeare Company, which works within the paradigm of Original Practice, took the responsibility of tackling this material with a grave seriousness. Their “Merchant,” directed by Kati-Grace Kirby and starring Rivka Levin as Shylock, is actually currently being remounted until March 30. If you’re in the Atlanta area this month, I strongly recommend the show.

In addition, theatre dybbuk, a Los Angeles-based company that devises original performances and “encounters” with Jewish thought, is currently touring “The Merchant of Venice (Annotated), or In Sooth I Know Not Why I Am So Sad,” along with its companion piece, “The Villainy You Teach.” Their podcast, “The Dybbukast,” also released three episodes to serve as educational supplements for this project: “The Merchant of Venice: Ghetto”, “The Merchant of Venice: Shakespeare in Performance”, and finally, “The Merchant of Venice: Annotated”.

These are only two recent examples of diligent and effective artistic interventions with “The Merchant of Venice,” but they’re not the first, nor will they be the last. Just as there are endless clumsy choices that will torpedo a “Merchant” production, no matter the intent of those involved, there is also an abundance of choices available that allow artists to successfully face the text and not be defeated by it.

Why does this matter?

To begin with, acknowledging that “Merchant” has been successfully staged in the past, including by Jewish theater practitioners, is to deservedly recognize a staggering achievement. To say that the show is impossible to ethically produce discredits the moral character of countless Jewish artists who have already done so. It dismisses not only their creative and intellectual labor, but also denies their power to wrestle with the text, a power that is almost always exercised in the explicit effort to locate the ethical and the moral. Doing it right is the concern at the forefront of any responsible artist’s mind when taking on “The Merchant of Venice.”

Saying it’s impossible to do “Merchant” well also exonerates those who do it poorly. We can only describe how improper these productions are by acknowledging that there is a universe in which they could have been good! It is necessary to assert that their bad choices were avoidable – otherwise, we have to let them off the hook.

It is crucial here to clarify that it was the tone-deaf incoherence of the direction that made “The Merchant of Venice 1936” an irresponsible production. But the presence of triggering material within a play is not an ethical violation. Even the Tavern’s “Merchant,” which was nearly faultless, was still an excruciating experience for me as an audience member. That was the point.

Theater, even when fictional, must always tell the truth. And the truth is, Jews do have a traumatic, painful history. We do have a brutal history full of suffering. We do have a history of horrors and tragedies. I have seen too many shows about those horrors concluded with false triumph or neat happy endings. I find obfuscation of bleakness at the expense of honesty to be far more unethical.

Of course artists have an obligation to engage respectfully with challenging texts. Of course artists must never underestimate the difficulty of certain subjects. Of course it is reasonable to expect that artists approach plays like “The Merchant of Venice” with a full awareness of the sensitivity such an undertaking demands. But it is not reasonable to demand that theater practitioners be intimidated by responsibility. That responsibility is our job. We know how to do our job, and that’s why Criterion should have done better.

It is simply not an option to relegate “Merchant” exclusively to the realm of the English classroom. The bottom line is that it’s Shakespeare. Shakespeare was meant to be performed, not read. The play loses the overwhelming bulk of its utility as an educational tool if it is restricted to the words on the page. Moreover, this would rob Jewish artists and audiences of direct participation in the text, a worthwhile pursuit in itself.

I want to conclude with a final image, from Atlanta Shakespeare Company’s production, a moment that I will always think of as “Merchant” Midrash:

When Rivka Levin’s Shylock receives the final ultimatum in Act 4 — convert to Christianity or die — she snaps, exploding into hysterical, deranged laughter, which within seconds devolves into sobs. Then, as Antonio and the Duke continue their lines, Shylock casts her eyes to the firmament, beating her fist against her heart in apology to the God she must abjure, the only thing she’d had left. It was this familiar gesture, this dark reprise of a Viddui, that finally broke my composure when I saw “Merchant” on opening night of the 2022 run. I wept too.

Kati-Grace, the director, had sat behind me the entire show. She’d watched me carefully for signs that something was too much, too far. She’d witnessed my spine go rigid when Tubal was verbally assaulted. She’d seen my fists clench when Gratiano stomped his feet during the trial to frighten Shylock. She’d checked in with me during intermission, and then again after curtain call. I state here what I told her:

The show was ruthlessly unflinching, and much of my experience as an audience member was one of deep suffering. I do not regret it. In fact, I cannot convey with enough vehemence how personally enriching the production was. Shylock was alone in that courtroom, no allies, no friends, no supporters… except for me. I had to be there. The audience had to be there. It was our duty to bear witness to Shylock’s crucible. It was a heavy, thankless duty, and I am grateful that the cup was passed my way.