Rob Shostak grew up in a traditional Jewish family in Montreal. But when the Syrian-Canadian artist moved to Toronto, he found himself without the close-knit Jewish community of his youth. A decade and half later, Shostak and his partner had a vision: Friday night gatherings with friends both Jewish and not. Enter 2020 and the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. With the world quarantining, the artist and his partner began marking Shabbat together and baking bread for their weekly meals.

Shostak enjoyed the tangible acts of mixing, kneading and shaping as a stark contrast to the never-ending scrolling, clicking and typing to which the world felt reduced during lockdowns. “Baking became a way to reignite my creative side, and the inspiration for this installation grew from there,” he told Hey Alma.

The artist put out a call for submissions on social media, asking anyone from first-time challah bakers to challah pros to send him the parchment papers left over from their baking process. Contributors could also send photos, stories and challah recipes along with their leftover parchment paper.

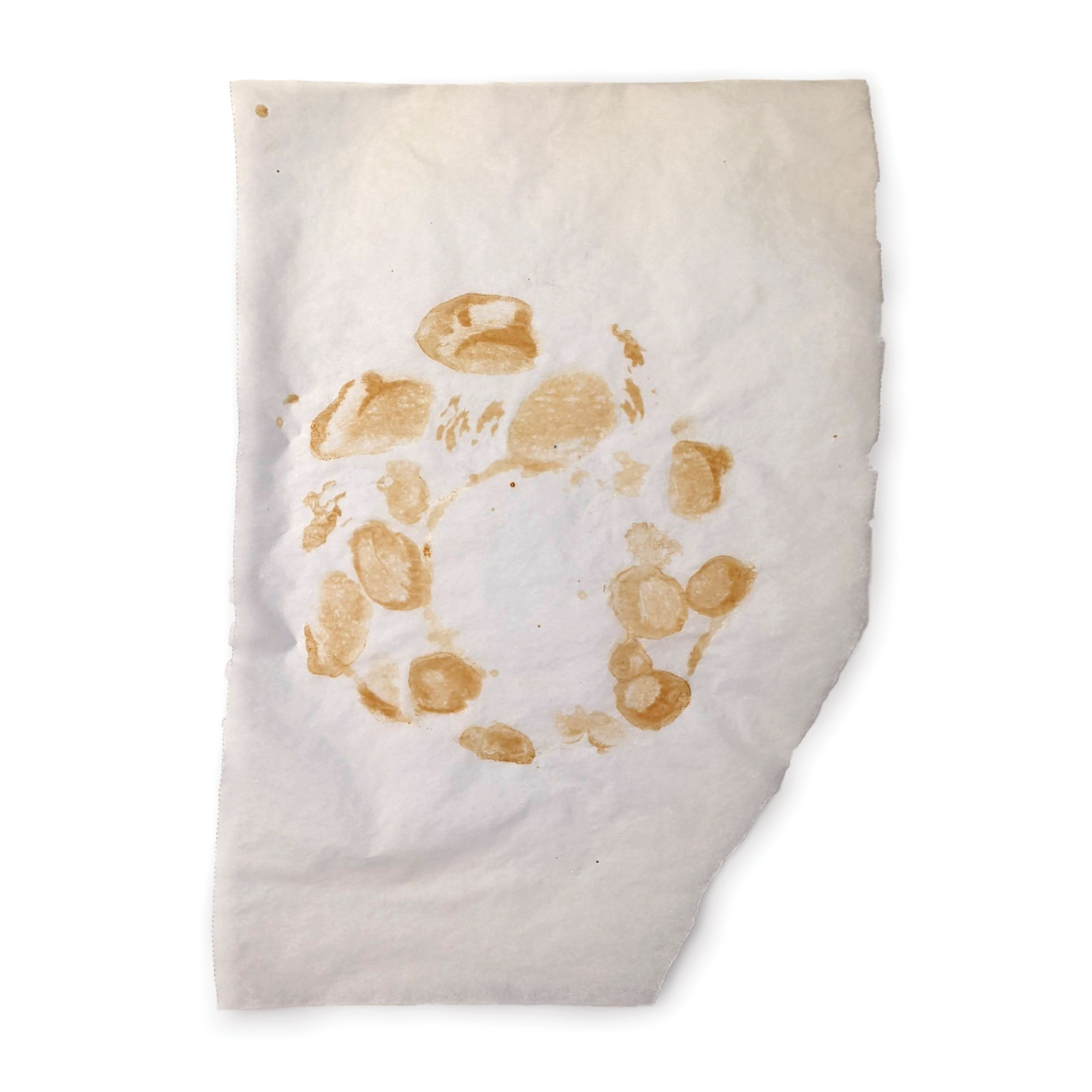

The result can be seen in Shostak’s exhibit “Parchment” for the Toronto window gallery FENTSTER, which features a collection of parchment papers that bear the imprint of challahs baked on them. He calls these fragile paper submissions “artifacts of Jewish life.”

I spoke to Shostak about his journey as a pandemic baker, if his work ever makes him hungry and the stories from “Parchment” that have touched his heart.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Did you grow up in a home with a weekly tradition of baking challah?

I grew up in a traditional Jewish home in Montreal among a large extended family that celebrated Shabbat every Friday night, and all the holidays together. The elaborate meals, of usually Syrian foods, would fill a home — most often my grandmother’s — with generations of our family at the large dining room table, with the overflow of “the kids” (me, my brother and my many cousins) anywhere else in the house we could sit with plates on our laps.

I don’t think anyone in my family ever baked bread, but the first morsel of food enjoyed would be the challah: blessed, torn and salted, with pieces thrown across the table to every person. The home baking was usually saved for dessert: Syrian sweets, simple cakes and ka’ak, either baked by my grandmother, my mother or my aunts.

Like many, I came to bread baking more regularly over the pandemic. I tried my hand at sourdough, but my starter gave up on me — dare I say I gave up on it — so I set my sights on challah. Celebrating Shabbat with my partner and spending part of my Friday baking bread brought order during the era when every day could easily blend into the next. The artistry of baking challah with its multiplicity of forms helped maintain the creative spirit in me. It opened a new world for me that I’m very keen to explore further.

What are your goals with “Parchment”? It sounds like you want to display the differences and similarities among the global Jewish diaspora, so how did you come to challah as the common denominator?

Much of my work examines the interactions between memory, time and place. I’m interested in how memories change or fade, how they are preserved or recalled and how geography and personal history mark and change these memories.

When baking, I noticed that the only thing that gets discarded when making challah is the parchment paper. The ingredients are mixed, the challah is consumed, candles burn, wine is drunk and everything else is a memory. Meanwhile, the only tangible thing that remains is thrown out.

I don’t have many photos from Shabbat dinners with my family because, out of respect for the day and the mixed levels of observance within my extended family, we didn’t take any. These parchment papers, as fragile as they are, become stand-ins for memories of Shabbat, family and community — the moments of gathering, bonding and blessing. They are artifacts of Jewish life.

So is that how you decided on parchment paper as the medium? There are so many different ways to bake challah — did you know that different parchment papers would reflect differences in bakes?

After one of my challah bakes, I noticed the golden-brown baked-in print left on the parchment paper. I took a photo of it and filed it in the back of my mind. The pandemic put me in an artistic hibernation for a while, but I knew there was something in that parchment print I wanted to explore eventually.

The used parchment papers are tangible artifacts of memory, where the act of baking becomes a form of mark-making. The oven acts as a darkroom, as if for a photographic process on the papers lining the baking sheet. They are part of the evidence of Jewish life, which historically was often made to to disappear by assimilation, oppression or attempts at erasure. Here, I’m presenting and preserving these fragments of time and memory.

Based on my own bakes, I knew there would be differences between everyone’s parchments, mostly because you never know what is going to develop on the paper. Different ingredients, shapes and ovens will create very different and unexpected results. Just like the bakers themselves, every print is so unique in form, texture and color.

The majority of them are braided, straight loaf prints from the Ashkenazi tradition, but some have been coiled, round challahs. A number of them have been formed into different shapes like hearts, swirls — there’s even a hamsa-shaped challah print. Some really caught my eye, including one that has a soft silhouette of braids but only to one side.

Have you noticed any similarities in the challah parchments by where they’re sent from?

I did notice how different recipes yield darker or lighter prints depending on the ratio of sugars, fats and eggs based on the various challah recipes I used. However, It’s hard to distinguish any regional differences between the parchment prints, especially now that people are sharing recipes and techniques online that cross their local boundaries.

While I was researching the geographic histories of challah, I found it interesting how, historically, Jewish communities would adapt traditions for the communities they’re in. It brings such a cultural richness to everyone. For example, in Syria, where bread was not formed into loaves, my family would bless twelve pitas for Shabbat representing the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

In Ethiopia, they make Defo Dabo in banana leaves. Sphardic traditions call for a round loaf using whole spices endemic to the area, while in Israel, it’s an eggless water bread. It’s all challah, and they are all part of Jewish tradition, because almost any bread can be used for the mitzvah.

As a carb-lover, I have to ask, does working on this project make you hungry all the time?

My apartment has really turned into a micro-bakery over the past few months, so it’s difficult to stay too hungry with so much bread around. Working on this installation has really opened up that world for me. I learned so much about baking, both the sciences and the artistry, and have fallen in love with it. I know I’ll be a baker for the rest of my life and am expanding my skills beyond challah and bread. I studied and worked in architecture for over 15 years and it brought my scientific and artistic sides together. Now that I no longer practice architecture, baking has combined those two elements in a new way that I’m excited to explore.

How many first-time challah bakers have submitted to your project? I know that you ask for photos of the challah, the parchment paper and any recipes and notes your participants want to include. Did anyone leave you notes about their experience?

I was overwhelmed by the reaction from the community in regards to this artwork. I received parchment papers from more than 50 people, many baking multiple times for this project.

There were a few notes from people that really made me feel the impact of the artwork. One person FaceTimes her father who lives in another city to bake with him. Another wrote about their new tradition of baking with their infant daughter, strengthening their relationship to Judaism. Many people baked their first challah for this artwork, and some have turned into weekly bakers who’ve shared their challahs with friends and neighbors.

This communal aspect of baking for Shabbat and the memories that Shabbat creates are a central theme this installation is exploring. Baking challah is a purposeful act that goes beyond physical nourishment. There is this feeling you get when preparing one that you are part of a collective of people across the world and across time, doing the same thing, with different recipes and traditions, but with the same intent.

I feel so grateful reading these notes and letters from everyone. It really shows the closeness and connectedness of the Jewish community, how none of us are strangers to each other.

“Parchment” is now open and on view 24/7 at FENTSTER (402 College Street, Toronto, Ontario) until August 2022. The public is invited to an outdoor opening on June 12th featuring challah bites and live music.

Shostak is posting the parchment papers he’s received on the @ParchmentProject instagram along with photos, recipes and more that people have sent him. He continues to collect parchment papers from challah bakes, so if you want to contribute, send him a DM on Instagram @robonto.