Toby Lloyd grew up in the U.K. with a mother who always attended Friday night services and a father who isn’t Jewish, but didn’t practice any other religion. He never had much of an interest in his Judaism until he started reading Jewish authors, such as Philip Roth and Francine Prose, in his late teens and early 20s.

When he started his MFA at New York University, he joined the campus Jewish society and ended up spending a lot of time with Chabad Jews at Friday night dinners. He’d never been around religious people, but was fascinated by the traditions, the rules and the stories. He started reading Torah and Jewish folktales.

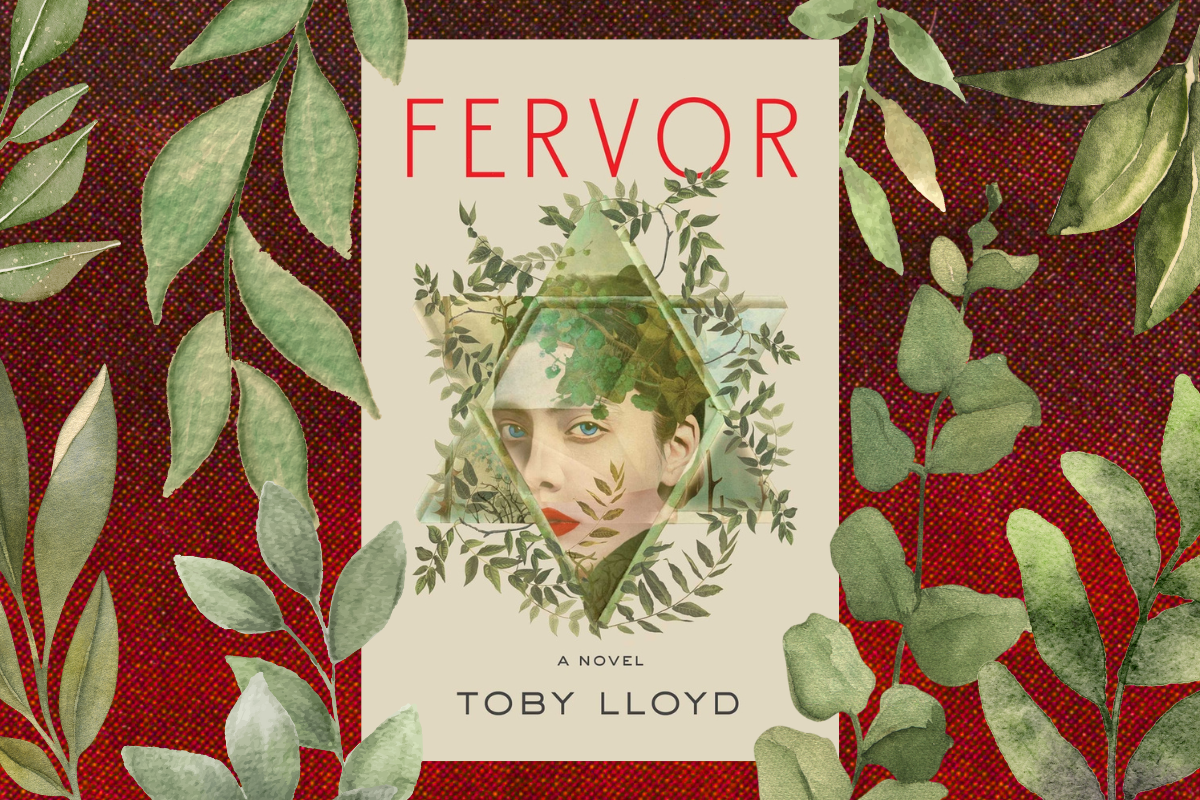

This inspired Lloyd to write “Fervor,” the story of the London-based, modern Orthodox Rosenthal family. The story follows Hannah, the Rosenthal matriarch and a well-known Jewish and Zionist intellectual; Tovyah, the youngest Rosenthal child, who is trying to find his own way while studying at Oxford; and Elsie, the middle Rosenthal child who has become consumed by Jewish mysticism, so much so that Hannah even believes her daughter is a witch.

But we often hear about the Rosenthals from an outsider’s perspective: Kate, Tovyah’s only friend at Oxford. Kate is Jewish, but grew up without much religion or cultural exposure. She finds Tovyah and his family fascinating. As she learns about their secrets, their fears and their contradictions, so do we.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Why did you decide to write this book?

For me, there’s lots of different starting points.

I am a big lover of horror movies. There are a lot of horror films that are supernatural horror films with a religious element. I’m thinking of “The Exorcist” or “Rosemary’s Baby,” or more recently, “The Witch” or “Saint Maud.” They’re all about Christianity.

And I was like: Where are the Jewish horror movies?

One of the big influences on this book is “The Hasidic Tale,” which were written in German and Yiddish and translated, thankfully, into English, so I could read them. And that stuff is full of ghosts and dybbuks and golems and witches.

Wanting to channel my love of “The Exorcist” and “Rosemary’s Baby” into something very Jewish, it seemed fresh. It seemed like something that I couldn’t think had obviously been done.

So I was like, I’ll do it.

You’re so right, Jews have a huge horror cannon! What else inspired you to write “Fervor”?

A few years ago, I became very interested in the Bible, in particular the long narrative sections of it in Exodus and Genesis, and later in the books of Samuel.

I’m not religious, I’m an atheist, I avoided reading the Bible throughout my life. I don’t know why I started, but I was like, oh, this is actually really good. It’s good literature. It just wasn’t the book I thought it was!

I imagined that it was this long rulebook, essentially, and telling people what to think about God.

I found that this is such an exciting reading experience for me. I was like, wow, I want to write something that’s very influenced by the Old Testament. But I want to do it in a modern sense.

I’d had this misconception that the stories that were being told would have an obvious moral lesson for readers: don’t do this, do that. A story like Jephthah’s story [a man burns his daughter alive as a sacrifice to God, but he is not happy about it], just doesn’t. It’s baffling and unsettling and that’s what I wanted my novel to be.

Can confirm that’s the vibe of the book: baffling and unsettling. But it’s also a really great family story.

There’s such a strong tradition of American-Jewish fiction. There is not so strong a tradition of British-Jewish fiction.

I was interested in writing a novel about a very Jewish, British family, inspired in part by my interactions with very strongly religious Jews.

I always wanted for the book to have lots of different ideas of what a Jew is. So there’s atheist Jews, there’s extremely religious Jews, there’s liberal Jews — which I think you call that reform Jews. Equally, there’s Zionist Jews, there’s anti-Zionist Jews.

I wanted to have a broad palate of British-Jewish experience in a modern book, sort of inspired by the Bible.

Is that why Kate is the narrator, much of the time, rather than any member of the Rosenthal family?

The story’s about the Rosenthal family. They’re the interest, they’re what the story’s really about.

I knew that I wanted an outsider to tell their story. It’s a well-trodden path in fiction that you have a very fascinating character who’s actually not on the page as much. I’m thinking of Gatsby in “The Great Gatsby.” He doesn’t tell the story, he’s not on the page as much as Nick Carraway is.

There’s a sense that you preserve something of the strangeness and the splendor of these very fascinating characters, by keeping them a little bit removed. So that’s why Kate tells the story.

The reason there’s parts of the story that are more of an omniscient, third person is that I knew that I wanted to tell things that are from the past and that she’s not there for.

We have to talk about the Israel stuff in the book. “Fervor” is set in 2008, when Israel also invaded Gaza on the ground. It was interesting to read it and be like, all the same stuff is happening right now — especially with the campus antisemitism that Tovya encounters, Kate watching the anti-Zionist movement unfold at Oxford and Hannah’s own ardent Zionism.

How did you write all the differing perspectives on Israel?

I don’t know if you’ve read Saul Bellows’s book, which is called “To Jerusalem and Back,” but there’s a line in it, which is quite funny, he says: “If you want everyone to like you, don’t write about Israel-Palestine.”

I knew that I didn’t want to use the book to advance any authorial take on the conflict.

I wanted to show characters having views that I believed those characters have. There’s more than two positions, but there’s two positions that come out in the novel. One is the belief that anyone who criticizes Israel is an antisemite, a belief which Hannah holds very strongly. The opposite belief is that Israel is a fascist state, a terrorist state and those who support it are fascists.

What I wanted to show is that if you are Jewish and you live in Britain, or you live in America, or you live in Canada, you can’t completely ignore what is happening in Israel-Palestine — even if you want to, because other people won’t let you.

I wanted to show the effects of what’s happening overseas for British Jews of various political persuasions. I think that’s an important part of Jewish identity — whether you’re a real Israel defender, whether you love the country, whether you can’t stand it — it still somehow impacts you as a Jew in in the West.

To not write about it therefore would be to not present a full picture of Jewish experience in the U.K.

Mic drop moment for me. We can just end the interview now.