There are a lot of haggadahs out there. A lot. Any Jew with an Amazon account or a decades-old family collection knows that. You can have a “30 Minute Seder” or a “Seinfeld” one. Each guide to the Passover seder looks to bring something new to the table: translations, commentaries, connections, personalities and illustrations vary from volume to volume. Not all of them could be considered works of art, but Emily Marbach’s new addition to the haggadah canon certainly is.

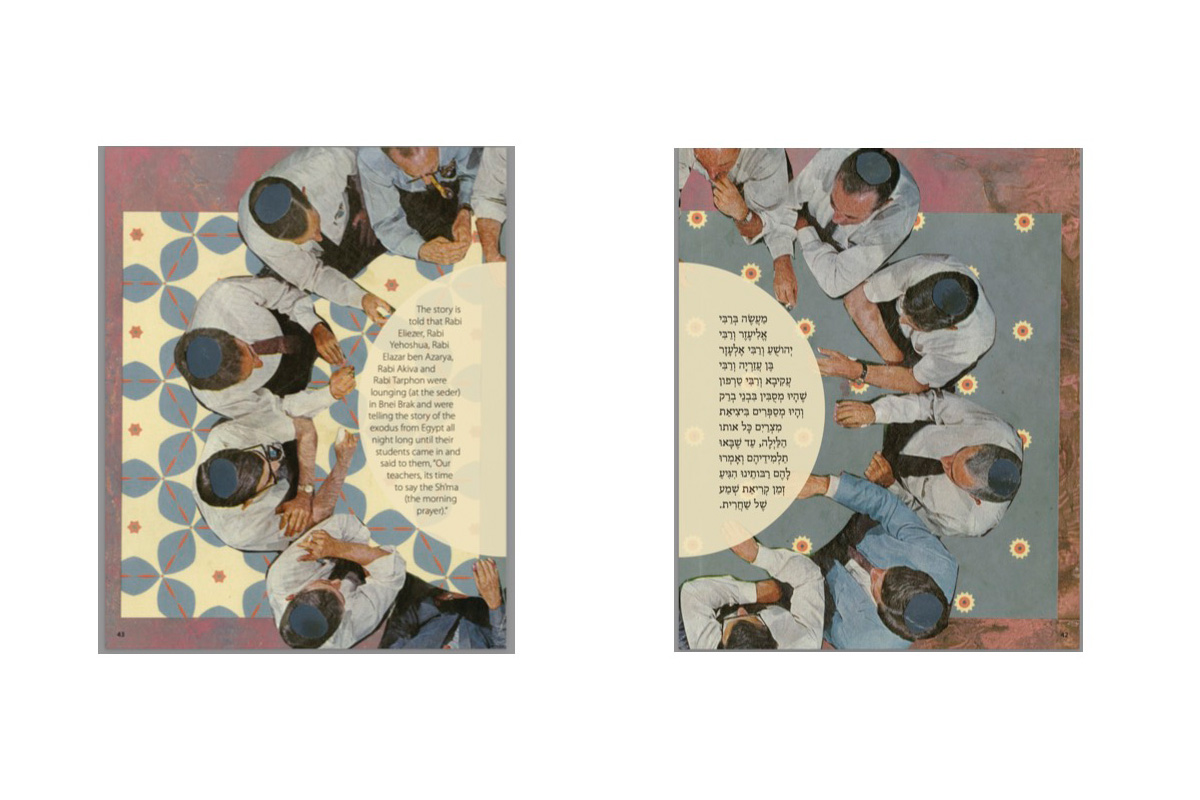

The “Collage Haggadah” is a self-published work from the 55-year-old Jewish artist based in Notting Hill, England, that offers exactly what the title implies. A refreshing seder companion, the comments are sparse, the language is clear and her original works of collage art are beautifully done. Born in Manhattan, with education in Tokyo and nearly three decades living in England, Marbach brings a lot of personality to the haggadah. She designed and translated the work herself over the course of the pandemic, updating or making new choices in the English wording based on linguistics and tradition. I had the chance to speak with Marbach about her artistic process and why this haggadah is different from all other haggadahs.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

So first off, the most basic question is why make a haggadah?

I’ve always been interested in haggadahs. My family are Chozrim b’Tshuva [secular Jews who become more religious], and when I was 6, they made their first seder. And little by little, they gained knowledge. I started going to [Manhattan-based Jewish school] Ramaz with my older sister, and we learned a lot about Judaism and Hebrew. But we had some influential friends in our lives that were quite Orthodox and they gave us a haggadah every year. And so, we built a big collection of them. Some of them were kind of dry and boring, and some were quite exciting.

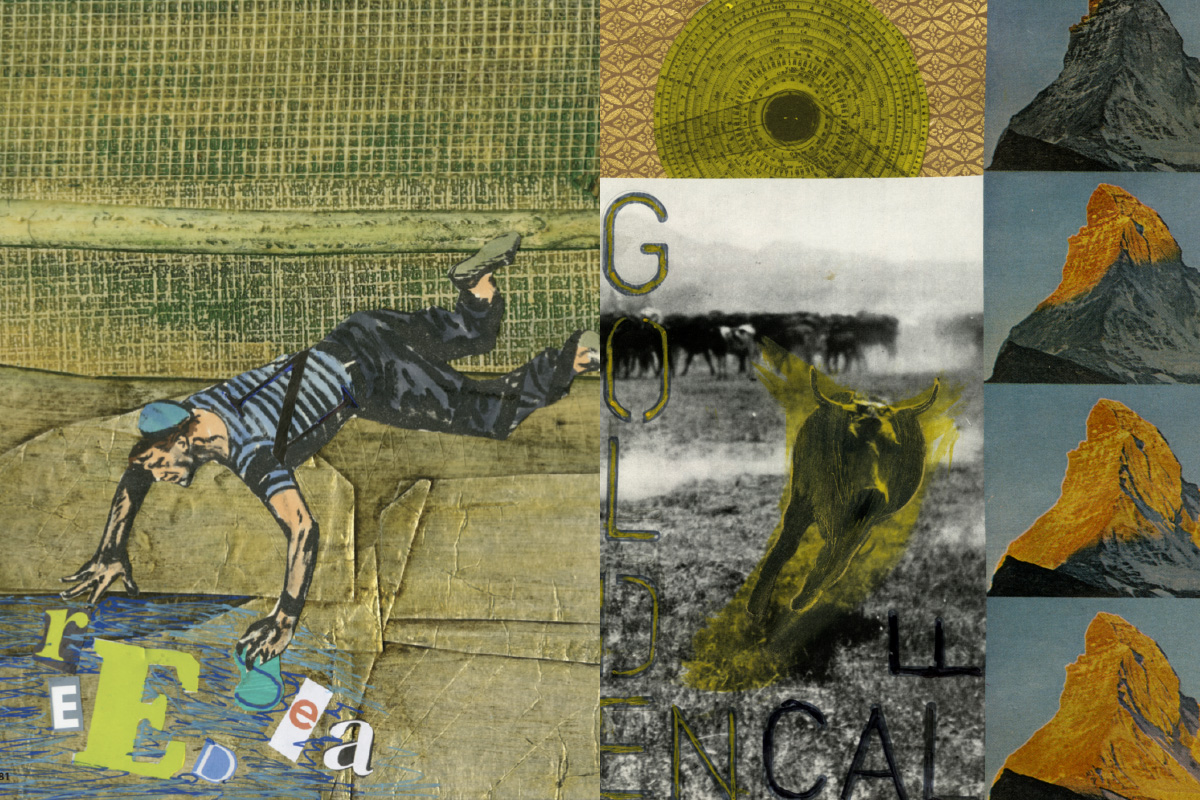

I had a boyfriend in college who was an amazing artist, so he and I were going to collaborate, but he didn’t really know anything about the subject and that project just never happened. So, I guess it’s been in the back of my mind for a very long time. And then one day, I just made the cover collage. Just seeing the people sitting around the table made me decide to stamp out all the 10 plague numbers on a piece of paper. A few months later, I saw a picture of a calf — a little horned calf — and I just thought of the Egel HaZahav [golden calf]. I found these really pretty mountains, and they made me think of Mount Sinai, so I put that together. So, then I had these two collages and I thought, “What else could I be inspired by?”

There was a critical moment when I just thought, “Wait a minute, I think that this could really keep me busy for a long time.” Then COVID happened, and then I really needed something to keep me busy.

You open your haggadah with a quote from Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel: “I love Passover because for me it is a cry against indifference, a cry for compassion.” You also mention the tangerine and the olive at the beginning, symbols some use on Passover to make the case that we’re not free unless all are free. Did you find that to be a guiding ethos for the haggadah?

I did. On one page, there’s a person leaving Egypt on a skateboard. I realized while doing this project that really that is one of the fundamental things that you want to do during the seder: to really, really imagine that you were there, and you left Egypt. If you can really believe that you were a slave, then you will be more compassionate to people who have suffered because you can empathize. Somehow, empathy is much greater than sympathy, I think. So that’s why [I included] the Elie Wiesel quote. I think that empathizing is about tikkun olam, fixing the world. And I think that the experience of the seder does bring you closer to thinking, “Wait, actually, there are so many problems in the world, and we need to fix them.” People can make that journey from slavery to liberation and create a whole new world.

A haggadah is text, but it’s also an instruction manual — it takes you through the path, the process. Was that in your consideration while you were creating it? That it’s not just about what the art is, but also how you’re taking somebody through their own seder?

Yes, I definitely try and have direct instructions. And also, from time to time, I say things like, “We do it this way, you can do it that way.” Also, in Dayenu, I didn’t actually translate that bit, I just transliterated it, because I thought most people really just want to sing along. The page is set up easily for them to catch on, because it is a catchy tune, and certainly you want to sing the chorus. I definitely feel like I’m pulling someone along through it.

How has your relationship with Passover and the seder evolved over the years?

Over time, my parents learned a lot while I was growing up. My father did end up taking the patriarchal position of leading the seder. Then, when I got married and moved to England, my father-in-law took up that position. But about 10 years ago, my in-laws started going to their son’s house in the States. We have quite a small family in England, so we started making the seders at our house. Because my husband’s really good at timing food for dinner parties and organizing, it worked out better that I ran the seder. It’s also just because I did have more knowledge and I think I do have this intrinsic interest. My Hebrew is definitely better than his. So, I led it and that’s how it’s continued. We also go to other people’s houses, and everybody does it differently. But I feel like it’s become quite an empowering thing, and it’s quite nice actually, as a woman, to be leading the seder.

The “Collage Haggadah” has a lot of fun to it. At one point a parenthetical says, “the size of an egg, for example, but don’t get me started.” It definitely feels like one underlying thing is that you want to make sure that there’s fun and liveliness. So, what does a seder that you’re running look like, feel like? What kind of experience is that?

We try to have a different kind of beverage for each cup. So, we often start with a glass of champagne. I don’t like to drink four cups of wine, to be honest. But I do try and buy lots of different kinds of grape juices for after the first glass. My little sister often reminds [before Passover], you can plant some seeds this week in little trays and seedlings, like parsley, and they’ll be popping up if you plant them now for the seder. So, we do try to have some kind of nice, organic centerpieces, and left over from when my children were small, we have masks of the 10 plagues.

We try to sing wherever we can. I’m a member of a choir, so I really do love to sing. And certainly towards the end, there are all the great songs. Even though the number of children at my seder are fewer and fewer as I age — I really have to kidnap some children or something — I do still hide the afikoman, and whoever is around has to find it for us to finish the seder. I’ve heard of people who take matzah and carry it on their shoulders. I can’t say that I do that. But I do try to encourage people to bring things that they’d like to contribute. Maybe this is a good idea, that I should try to get people to find funny things.

There’s a lot of art variety in your haggadah, from the funny to the tragic. Do you have any philosophy when it comes to collage? What’s going on while you’re creating it?

It seems like everyone’s very, very concerned about copyright. So I would like to say that all is fair in love and collage, although I do try and transform images. For example, I have Michelangelo’s picture of Moses and I really am not fearful that someone’s going to come and chase me over that. I’m also a printmaker, so I like to use as many media as I can, but I don’t want to overcrowd a piece — except in “Afikoman-Mania,” which is supposed to be quite chaotic.

In terms of a philosophy, in January of 2020, my plan was to collage for another six months and then give up collage and go back to painting. But then the pandemic hit, and I spent many nights, probably spent six hours a day, collaging. And I got to a kind of critical point where there’s actually very little conscious thought, that I just kind of amass things and put them together. For some reason, there’s a moment where I’ve just stopped because I know it’s finished, and it’s worked.

My mother’s quote in life is “more is more,” and I do think that it would be fun to spend a lot of time on one collage, but I work quickly and I find that you can do too much. Some things can get spoiled if you overdo them. I’m coming to understand more and more that I like whitespace.

You write in the book that this haggadah has no agenda, but at the same time, there are active choices that you make: pronoun choices, sometimes God is “himself,” “herself,” “theirself.” And there are other decisions about what is listed as a song versus what is written as is. What kind of choices were going into that? How much are you thinking about it as something that’s a project for you? And how much is it something that’s a project for an audience?

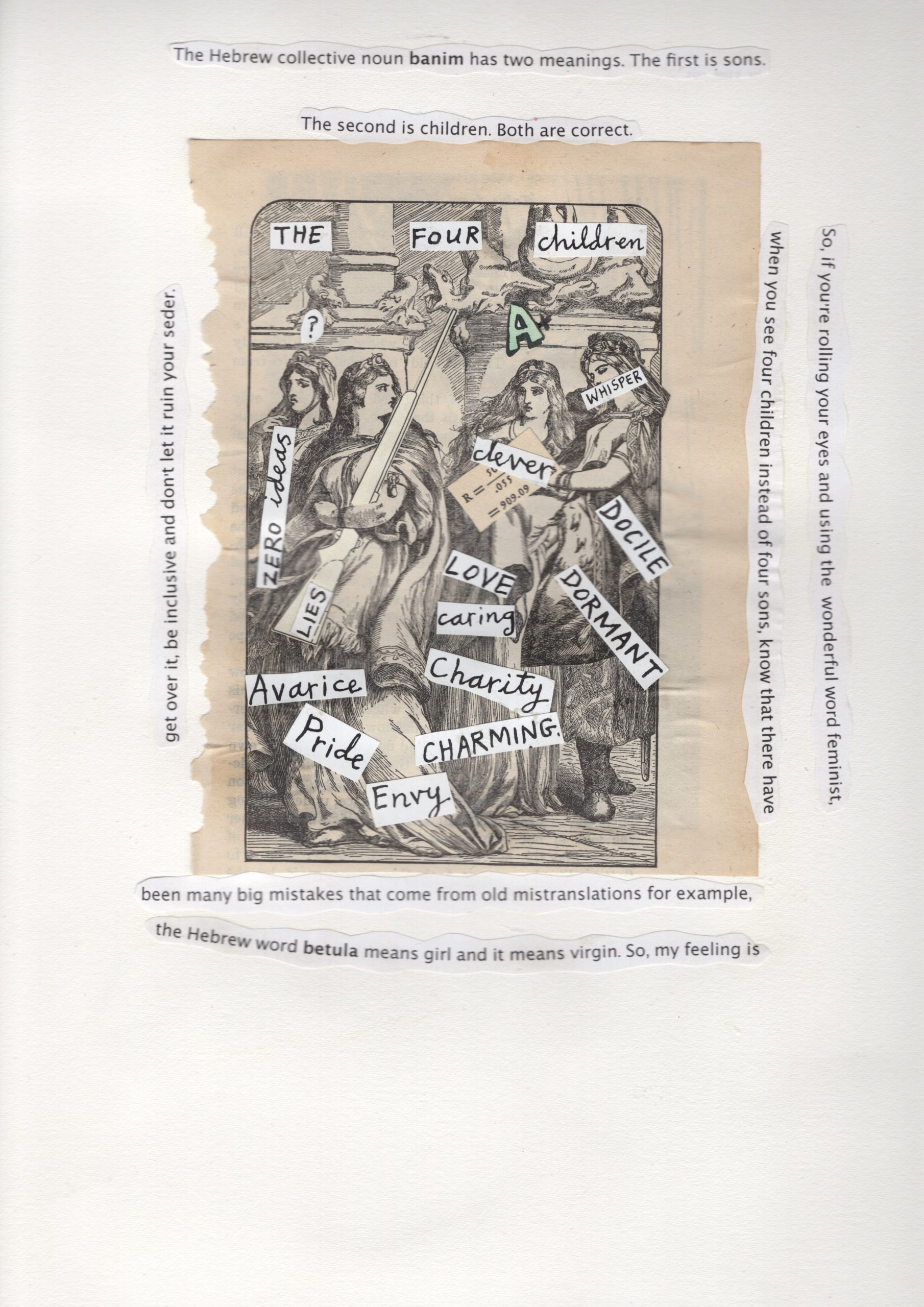

Well, in terms of the translation, I guess, we’re not in the 1970s. I had a cousin who would come to our seders when I was a child, and she’d always read, “Blessed be She, Queen of the universe.” And although we kind of laughed at her at the time, I really did want to try and eliminate the “Blessed be He, King of the universe” translation of the Hebrew. So, I tried to do as much of a direct translation as I could, but I really wanted as much as possible to eliminate that. So that was certainly an agenda. Certainly, as a feminist, I do think that it’s not very healthy to think of God as a man. Obviously, Christianity can’t get away from it, but in Judaism, in the canon especially, [with feminine references to God through] the shechina, there is definitely a female and a male side to God. So, having God be as non-binary as possible is definitely something I was trying to do. I explained on that page with the Four Daughters that actually I’m not trying to do anything radical here. But just choosing images of women, I thought it would be a tiny little grain of sand on the scale balancing all of the Four Sons. And yes, I think four children probably would have been a good idea. But these women just came to me and I needed to use them. So I did.

What was that translation process like?

I spread out lots of haggadahs in front of me. I had my phone with Google Translate, and I would read a line, and I would translate it, and then I would check and see what everyone else thought of the line. Also, I have a really huge Hebrew-English dictionary that I got from my bat mitzvah. So, I felt it was sort of a crowdsourcing activity.

I know that shamayim means heaven. But I don’t really feel like Judaism has the same kind of feeling about heaven that maybe the secular Christian world does. So, I decided to translate it as sky. In Judaism, we talk about Gan Eden, the Garden of Eden, where we want to spend Olam Haba, the next world — it’s not necessarily up. And I’m not convinced that God is behind the clouds. From my Orthodox background — I’m not Orthodox now — we used to sing the song, “Hashem is here, Hashem is there, Hashem is truly everywhere.” So, that was one word that I stuck with, and I’m waiting for somebody to come and say, “You know, shamayim isn’t sky.” I think there are probably a few little things that if you do actually read the entire English, you might find original translations, nobody else has written it that way.

If you wanted somebody to really understand what you’re trying to do with the haggadah on a visual level, what would be the one piece that you would want to show them?

The one collage that I really like and feel passionate about, but in a kind of lowkey way, because I feel sort of similar about a lot of them, is one where I actually use a plate that I made.

Collagraphy is where you make a collage with a lot of texture, and then you ink it and press it and make a print out of it. I had a plate that wasn’t very successful. And so, I decided to use it as background for a collage. It’s Nachshon Ben Aminadav and he’s diving into the Red Sea. I think he’s probably the first person that the phrase “leap of faith” is talking about. The Red Sea hadn’t parted. Moses is trying [to convince the Israelites that] God’s going to save them, but he leaps in. Because he knows that no matter what, the people are going to be liberated. So, someone has to take the first step, and it was very courageous because he might have gotten it wrong, but actually he was fine and the Red Sea did part. Who knows, he probably didn’t know how to swim. Why would he? He was a slave. I don’t know if I could say that I have huge faith, so I admire people who are really sure, and I think he really was sure.

Emily Marbach’s “Collage Haggadah” is available on Amazon or through her website.