You may have encountered Rachel Schragis’ art without knowing it: on lifted cardboard boxes at anti-Amazon protests in NYC, at the People’s Climate March, in Zuccotti Park at the height of the Occupy Wall Street movement. That last piece, a flowchart with the heading “All of Our Grievances Are Connected,” now belongs to the Met. It was the first iteration of what has become her signature — complex charts of words and images that present struggles of our time.

Schragis, who is Jewish, took on antisemitism as her latest visual translation challenge. “Unraveling Antisemitism,” made in partnership with Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ), differs from much of Schragis’ work in that it didn’t originate in the streets. But like all the art in which she participates, it grew out of deep collaboration — a 40-page pamphlet on the subject by JFREJ, community interviews, illustrations by Rebecca Katz, and long group discussions. And she wants people to know that.

“Culturally, we really want to look at one person as the protagonist,” she told me. “It was a revelation for me that I had to unlearn the idea that my creative expression was the center of the goal. The more I learn that, the better work I do.”

I spoke to Schragis about making art in the service of change, her relationship to her Jewish identity, and how the Talmud is a flowchart.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

How would you introduce yourself and your work to someone who knows nothing about you?

Wow, what a question. I often introduce myself as a cultural organizer, and a visual strategist. Or I say, I’m a social movement cultural worker in visual strategy. I’m trained as an artist, an educator and a community organizer, and I use a lot of those skills together to support groups that are doing the work of social movements.

That’s actually very concise! Are there eras, or sections, of your life that you associate with each of these elements individually? Or have you always been doing them all in conjunction with one other?

Well, I’m talking to you on the occasion of the launch of a flowchart [about antisemitism] that I made, and I would say that my work has two distinct categories. One is projects that I do in the street, in collaboration and community for public protest and civic engagement. The other is illustration work that ends up in people’s homes and communities and offices. In the second category, you see my hand more; I am more the maker, the artist. The other category is a deeper collaborative process where I’m lending in skills and working with other artists — so it’s less me, Rachel, the artist.

I think of my life as a pendulum between the two, the organizing projects and capital A Art-on-the-wall projects, because each one makes the other one possible. Working together in the street, in social movements, is what helps me understand what people need charted, and how I can be useful as a person who makes the art that I make. And then the Art that I make can end on the wall at your friend’s house. The combination helps build trust and understanding about what role people with visual skills can play, and build the relationships that make it possible for us to do creative projects together in public.

So do you consider these two kinds of art — the art that you make in the street and the art that you make for the wall — fundamentally different? Or are they just consumed differently?

I was raised to think that the greatest honor would be to have a solo show at a museum. Instead, I asked myself, what if I thought of it this other way? What would change about what I made if protest work were the most meaningful thing I could do with my life? Because it is. And so I’ve tried to orient my work around the idea that it’s the greatest honor to make things together for protests. I now think that the things I do collaboratively in the street are the most important because that’s where power is confronted, and challenged, and won.

I also think that the intimate conversations we have in each other’s homes are a critical way the transformation happens. I think of that as a feminist practice, that what happens in home spaces is transformative. As I make these posters that are reproduced, and that take a lot of time to read, people’s most common reaction is, “Wow, I’m gonna take some time with that one. I’m gonna put that up in my bathroom, so I can read it while I’m brushing my teeth.” I’ve learned to see that as an honor, too, because that’s a quiet, longer-term, more subtle way that we reshape each other’s thinking about the world we live in. And it supports the work of collective transformation.

So, I’d say they’re different. They’re both pieces of a puzzle.

How did you start making art? And was it always with an eye to social justice?

I started making art, like a lot of people do, as a young person in school. And I think that’s a critical piece of the story, that I grew up in the owning class in New York City and I had access to a lot of art education. It was taken as a given that that was a meaningful thing for me to do with my life, and worth risks in terms of stability or other kinds of opportunities, to build myself up as a person. I think that gets obscured sometimes since what I do is about challenging the owning class. It’s deeply important to me that I commit myself to a lifetime of work of dismantling the owning class as someone who was raised as part of it.

I started making artwork because it was liberatory to me. Everything I figured out about myself, I know from making art; that has always been true. So it feels clear to me from my own life experience that the act of making things visually together has so much to lend to collective problem-solving. I can tell you stories about how I stumbled into a lifetime at the intersection of organizing work and visual arts. But it comes from the gift of the truth that I know about myself, which is that art is a form of liberation.

How did you eventually come to start making art in the form of flowcharts?

I studied sculpture in undergrad, and I made a piece of art where I saved my trash for a whole year and made art about it. That taught me that there’s no such thing as “my trash” — if my housemate makes me dinner, is that their trash or my trash? In my early 20s, I confronted the idea there’s no such thing as personal responsibility. If I was going to make art that was “helping,” it was towards some more collective thing.

I started making little drawings of what I was thinking about this, because I was making literally piles of trash, and people didn’t think of them as cool sculpture. But people really did respond to the writing about it. And I came to understand that a lot of people, especially people who aren’t trained as artists, care about and rely on language to help them understand the world — and that’s not something I should shy away from.

So I got obsessed with making flowcharts. I made them out of everything; I made lists into flowcharts all the time. I was 23, and I went to Zuccotti Park, and someone handed me a list of the grievances, why people were occupying the park at the beginning of Occupy Wall Street. And I said to myself, this is the chart I’ve been looking to make. I made the chart and put it up on my own Facebook. And people emerged from the movement to help me figure out how to print copies and how to distribute it, how to make large copies for the street. People started asking me to speak about it. The Occupy movement taught me about the roles that art could play in movements by showing me how this thing I’d made was useful. It was the first time in my life I felt like I had made art that was actually useful. People would point at it and say, “This is what the movement’s about. This is what we demand.” It was so much more useful than the list.

One other flash point moment was when I started painting banners for people’s actions. That’s what people know to ask artists to do. Then, I was asked to make a flowchart about climate change. And it was so hard. I had a month to do it, to turn a speech of Bill McKibben’s into a mind map, and I cried every day because the information was still overwhelming. And I thought, this is an issue of my time that demands the best of my skills; I don’t know how to make art that’s good enough to tell this story. That has made me very committed to doing a lot of climate organizing.

When you are presented with an issue that you’re trying to translate into a flowchart both visually and verbally — to make it more digestible to people — what is your process? How do you start? Are you moving index cards around?

It’s a magical journey every time. I’ve learned it takes about five years, The first year, you’re just figuring out what the chart should be — that’s the year I’m in right now, because I just finished one. I start with some big questions, some complex things I’m seeing happening in the movement. Then there’s a year of gathering information: what’s the data, what are the facts? Most of my charts have started with an essay or a list. The most recent one, on antisemitism, was a 40-page booklet. I definitely do some cutting things up into bits and mapping them out on the wall and putting things on Post-It notes and chewing on the information. Then, it takes two years to actually turn that chewing into a chart. And then it takes a year to figure out how to share it with the public and have it be absorbed and useful and distributed.

Your latest project is about antisemitism. What is your relationship to Judaism? You said you grew up in New York as part of the owning class — did you feel Jewish growing up, is your Jewishness tied to New York? How has it changed over time?

My life experience is an archetype of one kind of Jew in the United States. It’s worth saying explicitly that there are many kinds of Jewish experience that do not rise to the surface the way that mine does. And that’s about proximity to whiteness, access to whiteness, access to wealth that comes from proximity to whiteness.

I grew up a Reform, secular Jew from an owning-class family in New York City on the Upper West Side. I think owning class, Jewish, New York culture is as close to Jewishness being in the air of everyone’s experience as we have in the United States. There were so many Jews around me that it wasn’t a major part of how I thought. Ashkenazi Jewish experience was normalized. It was meeting Jews with different kinds of experiences later in life that taught me that how important it is to my identity that I’m Jewish.

I grew up with a kind of firm ambivalence about Jewishness. Whenever we did Friday night services (which was not every week, it was important that we didn’t do it every week, but we did it sometimes), my father always joined the prayers a little late, like one line in. It was like, we do this thing, but we’re not totally sure why.

I would say that I didn’t have a lot of clarity about what was going on there as a young person. It’s been participating in multiracial cross-class movement work that’s helped me understand what I think is going on — and also helped me understand that I need Jewishness to stay in the work of trying to change the world. It’s really hard, and you need your ancestors with you!

An aha moment for me came when I was organized by Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ). When I was a young artist, during Occupy Wall Street, JFREJ found me and invited me to apply to the Grace Paley Organizing Fellowship. I was connected with an amazing arts activist puppeteer named Jenny Romaine for mentorship. I was talking with her about learning to move through white shame and white rage, and she helped me see some of the ways of understanding my own traditions — that I had ancestors and culture to pull from. It doesn’t make me any less white to be Jewish. Race and ethnicity aren’t the same thing. But it helps me imagine what decomposing white supremacy could look like and what my role is as a white person, to bring a culture to the table that is mine and lean on it hard, and not say that culture and lineage and legacy is for those other people over there — which is something I think a lot of white people do.

So now I’ve grown into really needing Jewish holidays, really needing the small set of Jewish prayers that I learned as a young person. I don’t have as much Jewish literacy and knowledge as I wish I did, or as a lot of people do. But the pieces I have and the pieces I learn from friends are how I stay sane as a movement organizer and how I deal with despair.

As you make art with a social conscience, do you think consciously about tikkun olam at all — the Jewish value of healing the world? In your mind, is there anything Jewish about your art when it doesn’t contain explicitly Jewish themes?

Jenny Romaine pointed out to me the obvious fact that the Talmud is a flowchart — and that the way that I make artwork, which is about naming and celebrating complexity and understanding, about debate and making contradiction beautiful as a way to deal with said contradiction, a way to deal with complexity, is an extremely Jewish thing to do. And it makes me laugh, because I didn’t think of it that way. But yes, I was raised to value those things. And now my artwork does it to a kind of absurd degree.

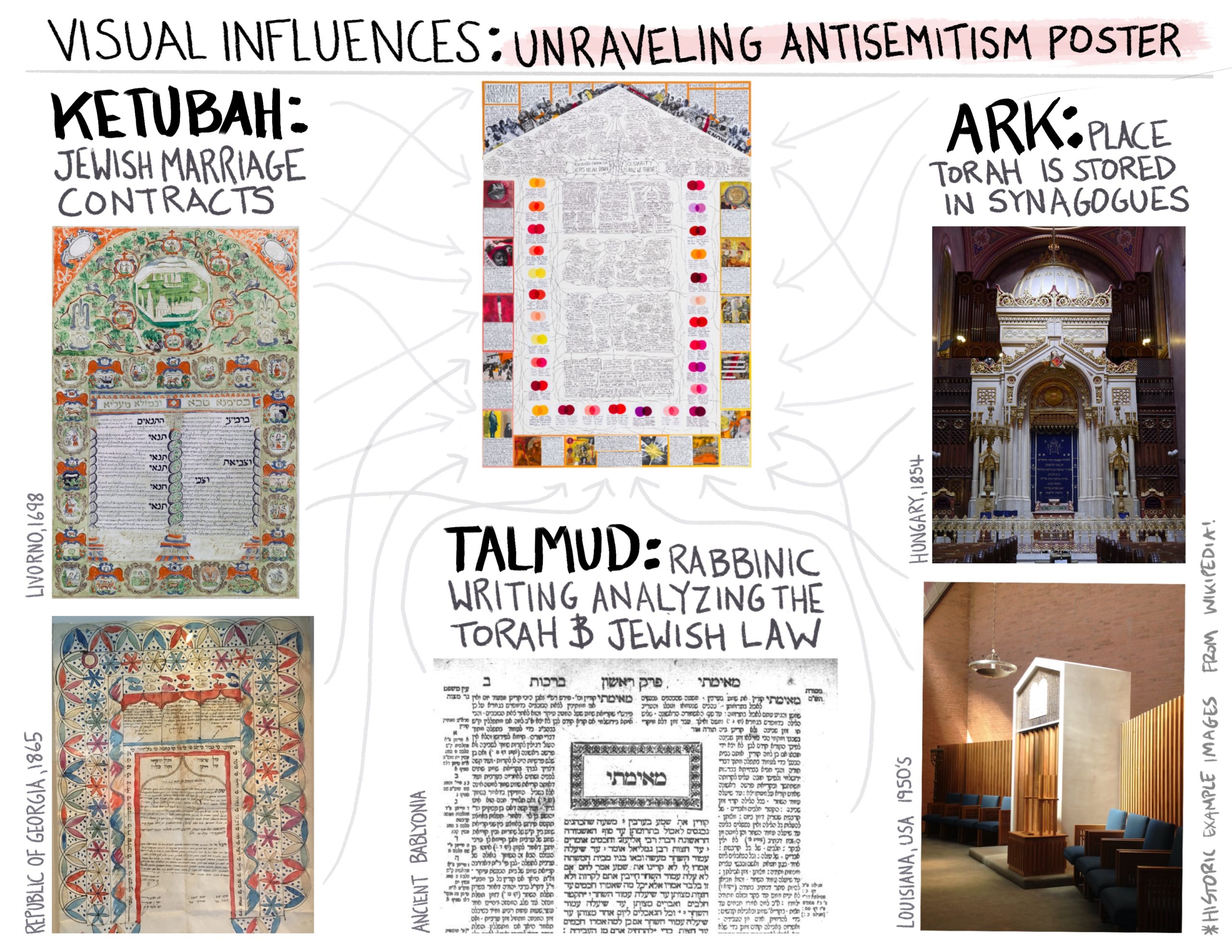

This most recent piece on antisemitism is the first time in my life that I’ve brought that to the surface. The opportunity to make a piece about the story of my people, Jewish peoples, allowed me to do some deeper thinking on this: If the Talmud is a flowchart, what else do I have to learn from the visual forms of my traditions, from other people who have chosen to celebrate questioning and complexity as a way to deal?

I spent a lot of time looking at ketubahs (Jewish marriage contracts). I also looked at illuminated manuscripts, ancient Jewish texts, for some of the different ways in which we have used pattern and abstraction, and also some figurative work. There are things that Jewish traditions have in common with some Islamic world and Muslim ways of visually communicating information, and ways that we can embody an alternative to Christian hegemony in our visuals.

One thing I’m very curious about in this poster is my theory that many different kinds of Jews see it and know that it looks Jewish. I don’t know, I haven’t had to test this a lot yet. But when my friend Ahmed came to my studio, he didn’t see that it looks Jewish. He’s not Jewish, he’s Muslim. I hope that in people’s homes, it can be a way that Jews explain, to each other and to non-Jews, what “looking Jewish” could look like. Why does it look Jewish? Well, it’s nonlinear. It connects to itself. There’s a pattern around the edge, right?

I love the concept of the Talmud as a flowchart, that is so brilliant. I’m curious if this project felt different from previous ones for you. It’s, at least in part, about antisemitism. And I wonder if that felt more personal, making a flowchart that was about a kind of hate that could be directed at you.

Every Jew has experienced antisemitism, and every Jew I’ve ever met is confused about whether and when that has existed. As a person with a lot of privileged layers of my identity, it’s a lot harder for me to give myself permission to understand myself as the victim of oppression. Because, you know, intersectionality — there are also ways in which I perpetuate oppression. I feel like I’m asking questions constantly in multiracial movement work about whether I’m bringing internalized antisemitism to the table, the shame about some of the ways in which I’m conditioned — or are people putting it onto me? How that interacts with the other dynamics in the room is confusing and could have its own whole chart. We didn’t talk a lot about internalized antisemitism in this poster, we couldn’t do everything.

Making this one felt scary, in a different way, because the content feels vulnerable. Are people going to believe me that this is true? That has never been a question that I’ve asked myself in a poster. But so much of the meat of how antisemitism operates is around conspiracy theory, in a lot of different ways. And so I had to move through my own fear: Are people around me going to think that I’m telling a conspiracy theory? No, no, they are not, this is what’s true.

This is the most deeply collaborative project I’ve ever worked on. It doesn’t tell just my story at all. By the end of the process, I had very little to do with the content decisions. I was facilitating who should decide how we talk about these different issues, and then having conversations with them and reflecting, but every single word on the poster went through rounds of feedback and debate with groups of Jews of a variety of different race and class experiences from me. So by the end, it made me really feel like part of a community.

Tell me more about the process of creating this particular poster. Who were the major collaborators? And how do you collaborate in general?

As a fine artist by training — and by like, young adult dream — I used to think the individual was the center of being an artist. But many people who are not trained as fine artists, who didn’t go to art school, learn how to collaborate really well. My closest collaborator went to design school; people who go to theater schools literally can’t do most worthy projects alone.

There were many phases of this poster. I learned that being collaborative doesn’t mean that there’s not more responsibility and leadership for me. Often, I was really scared of the kinds of choices that I had to make on behalf of the community to keep it moving forward. Some of the organizers I worked with at JFREJ confessed to me when it was done that there were moments in which they felt, and I felt, that the piece was impossible to ever finish, and we weren’t sure we would ever finish it. But it was rude for them to say to me that they had that doubt, and I had to show up confident as the artist who was shepherding it. I would come to a meeting with a whole notebook of drafts, and I’d have to choose which one to talk about, and which ones to make decisions about myself.

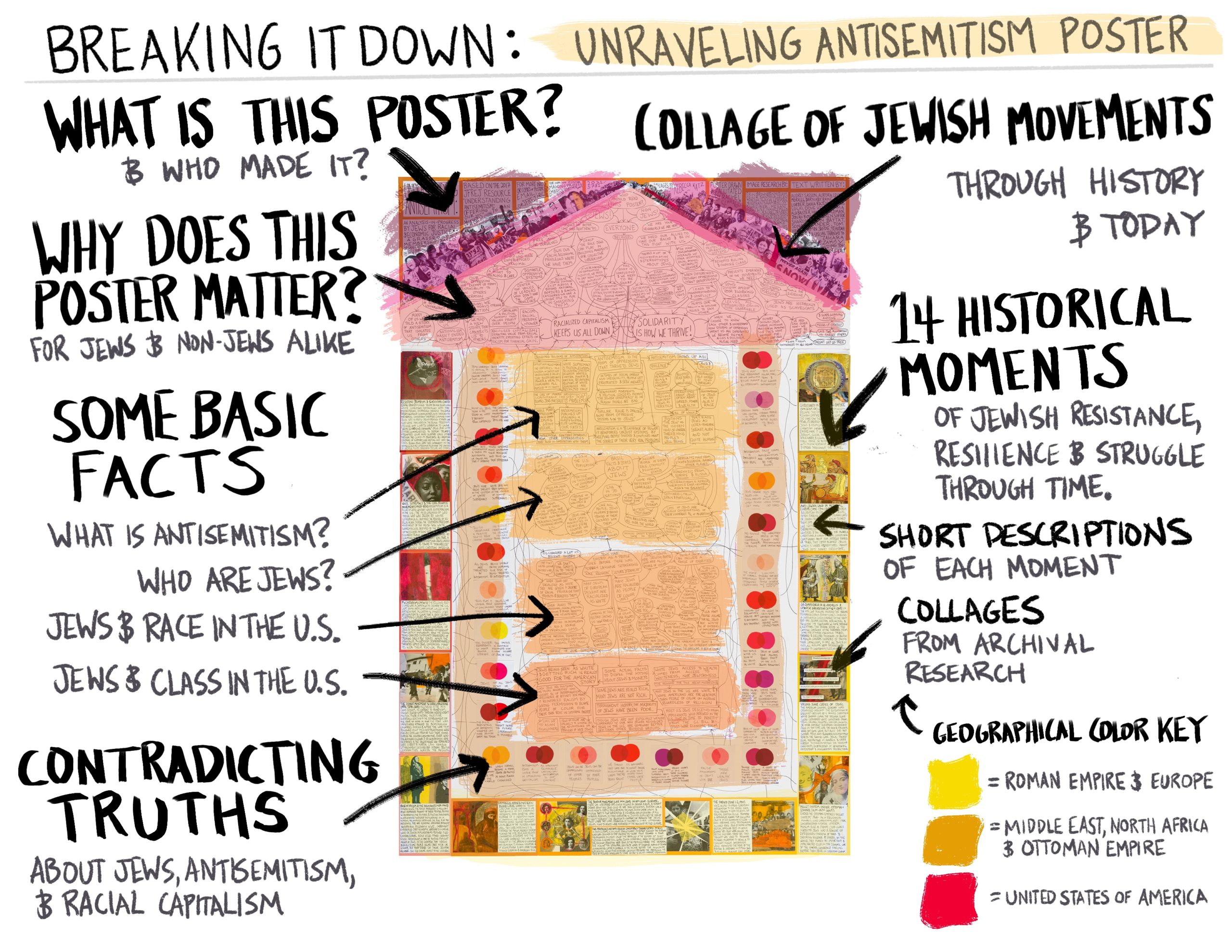

This piece is based on a booklet called “Understanding Antisemitism” that JFREJ made. They wrote that booklet after being asked by non-Jewish ally groups to help do trainings on antisemitism. When JFREJ started tiptoeing into that work, they discovered just how fundamentally confused their closest collaborators in the movement were about the history of Jews and who Jews are. So they decided to put some basic information out.

But writing “basic” information about antisemitism is really hard. The first pass was this highly collaborative, four-year-long booklet that included the work of poet Aura Levins Morales and the deep research of JFREJ staff member Leo Ferguson and other incredible historic research by JFREJ’s Mizrahi-Sephardi caucus. Big pieces of truth finding went into this 44-page booklet. Some people read it. A lot of people didn’t read it, because it’s a 44-page booklet. It got a lot of things right. And there was a lot of debate about some things that they didn’t land. So there was a lot of analysis. This poster started with the kind of complex soup of the first booklet and all the feedback to it.

I’m sure you learned a lot while making this antisemitism poster. But is there any one thing that you learned that really surprised you, or that’s with you daily now?

I think the biggest piece of new learning for me was about Mizrahi and Sephardi history. Two years into the process, I realized we couldn’t actually do right by this poster without telling historical stories — and therefore we couldn’t do this poster without illustrations, because you can’t really visualize history. We brought Rebecca Katz into the project and she did this whole other separate, mind-boggling, community-based archival imagery research collage process. It’s its own piece within the project and vision within the vision that she proposed. She said, “Oh, I shouldn’t just do illustrations, I should do this other community process.” And then we had to pick 14 moments to be examples of stories of what antisemitism is in the world, because that’s what fit on the chart.

I knew, of course, in the abstract, but it wasn’t until I went to workshops led by Mizrahi and Sephardi JFREJ leaders about the history of Jews in the Middle East and North Africa that I was able to feel that the history is as complicated and messy as my own Ashkenazi Jewish history as a Polish Jew: the relationships between safety and oppression and violence; periods of deep intermixing of Muslims and Jews; stories of Mizrahi and Sephardi communities moving to Israel and other places in the world, entering diaspora. Just because my story is the most known version of the Jewish story in the west, it doesn’t mean other stories are less ripe or complicated. And I learned about my uncle through marriage, who entered my family when I was in my 20s, who is Mizrahi. Through making this poster, I got to talk to his sister and learn more about my own family.

Has collaboration worked similarly on other projects? The inversion of the Amazon Smile logo, for instance?

It’s a story of cooperation, too. The idea of flipping the Amazon logo upside down, so it’s a frown instead of a smile, was an obvious idea. It’s in the air, many people do it. The first time I saw it was workers organizing across Europe striking against Amazon. I was asked to work with my collaborator, Josh Yoder, on protests against Amazon in New York City before the whole HQ2 thing happened —smaller protests against Amazon’s white supremacist practices. We wanted to use this obvious idea of making the smile into a frown and try to figure out how to make the frown more powerful, more real than the smile. We didn’t want people to see the frown and think, oh, that’s a cute hack of Amazon. We wanted people to see the smile and think, no, that smile is wrong. It’s really a frown. It was a response to the reality that Amazon is so built into our lives that we could not boycott them. So we have to fundamentally change how people associate to a brand that is amazing and magic — who doesn’t love Amazon? — and to see the underbelly of it.

That was really the work of Josh, who is an amazing graphic designer and whom I now do all of my work with at Look Loud, our shared creative home. He changed the shape of the eyes in the logo so that it wasn’t just a frown — it was an angry frown. We also put it on a physical box. And when we released these during the HQ2 fight, the week after we brought the box to the street, Amazon hired a new PR firm and started placing big boxes of free books at public schools in New York City. So it became the battle of the box. We thought this showed the threat of the movement.

As someone who is constantly trying to make it easier for people to wrap our minds about current crises, do you feel that there is one pressing issue that defines our time?

Yes, and no. You’ve seen the heading of the Occupy poster I made that made this lifetime of my artwork possible: “all of our grievances are connected.” There’s also a song that I wrote for another piece of mine that goes: (singing) “There is one question with 1000 answers, or perhaps only one answer to 1000 things to ask. But hey, don’t you know there’s no need to feel dejected? Because all of our grievances are connected?”

I really don’t think that there’s more than one issue. There’s different manifestations.

I could give a more practical answer: I feel deeply committed to organizing around climate change. I think that it is an existential issue that connects the questions of systemic racism to the questions of science and technology and society, to the questions of international collaboration, to the questions of land and indigenous sovereignty. It pulls in all of the existential questions of our time. But I actually often think it’s quite offensive when people say climate change is the problem of our time, when that’s not engaged with deeply.

So — what’s next? Do you know?

I’m back in the street prep component. It’s a very busy time in the climate movement because the next U.N. climate talks are at the end of October. Look Loud is currently working with two different sets of folks mobilizing. Greenfaith, which does international interfaith climate organizing, has days of action, October 17 and 18. We are supporting all different kinds of faith communities to show up visibly as people of faith, to bring the moral gravitas of our faith to the climate crisis. It’s been really interesting to come into the multifaith community as a Jew. The other group is the Build Back Fossil Free coalition, which is a U.S. project to bring together all the grassroots movements to stop different pipelines and say to Biden: no pipelines, no fossil fuels, you have the power to write an executive order to stop all this bullshit, do it. They’re taking five days of civil disobedience October 11-15, so we’re deep in slogan development, etc. And stay tuned five years from now: There’ll be another poster.

You can buy a physical copy of the “Unraveling Antisemitism” poster here.