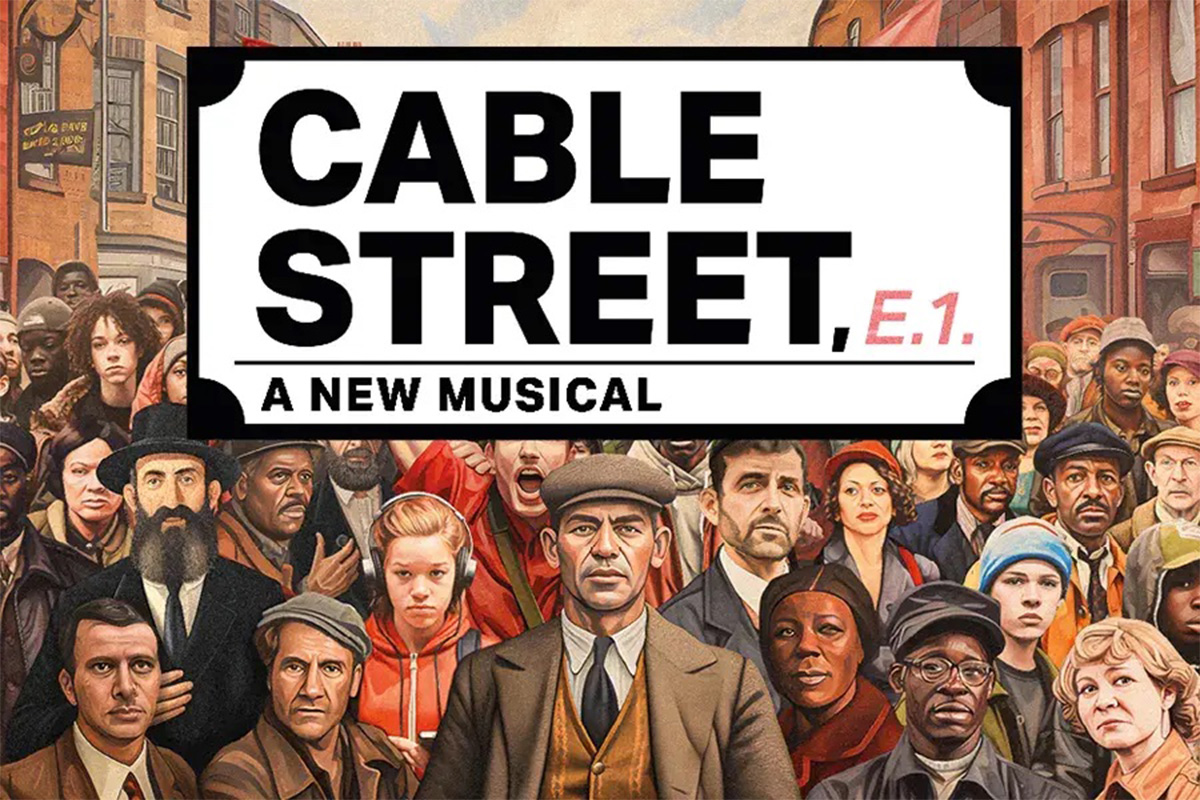

The new musical “Cable Street,” showing at the Southwark Playhouse in Borough, London, tells the story of the battle of the same name, a 1936 clash between fascist demonstrators and the residents of the East End through which they marched. The story is set both in 1936 and in the present day, and the key action takes place via three main characters: Sammy Scheinberg (Joshua Ginsberg), a Jewish ex-boxer in search of a job, a young Irish communist Mairaid Kenny (Sha Dessi) and working class Englishman Ron Williams (Danny Colligan). Around them is a talented cast who multi-role their way through all three overlapping stories. It’s a moving production, and a wonderful tribute to a crucial part of London immigrant history.

The Battle of Cable Street refers to a series of clashes on Oct. 4, 1936 that were instigated by a march staged by the British Union of Fascists (BUF). The march was provocatively and deliberately organised to take place in the East End, an area with a large Jewish population. In the lead-up, the Jewish People’s Council raised over 100,000 signatures of East Enders on a petition calling for the march to be banned, but the Home Secretary John Simon denied the request to outlaw it. The Metropolitan police, including the entire mounted division, were stationed all throughout the area in protection of the BUF. Anti-fascist marchers of all identities — Irish, Jewish, trade unionist, communist, anarchist — rallied in the hundreds of thousands in counterprotest. These anti-fascists built barricades on narrow Cable Street and its side streets in order to block the BUF from passing, and police attempts to remove the barricades were met by hand-to-hand fighting. When Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the BUF, arrived on the scene, police instructed him to leave the East End in fear of even greater unrest.

Emblematic not only of resistance to fascism but also of an incredible solidarity between different groups of oppressed people, this musical recognizes Cable Street’s historical significance and the power of continuing to champion collective action against hatred. The music is incredibly uplifting, and I genuinely found myself quite overcome with emotion and close to tears on a couple of occasions. The production was a little rough around the edges, but this didn’t bother me. It had a lot of pluck, and a lot of chutzpah.

The influences of Lin Manuel Miranda felt hard to miss as our young Jewish protagonist Sammy — L’Chaimilton, if you will — raps about his struggle to make a difference set against inspirational background oohs and ahs. The music was incredibly enjoyable while it was happening, though if I’m being truthful, nothing quite stuck in my mind after the fact; hopefully at some point a cast recording will be available, and I will be excited to go back and listen to a great soundtrack.

One thing that I found especially moving was the integration of Jewish prayers, in Hebrew, into big group numbers, enhanced by the diversity of the cast — watching a stage full of people embrace Jewishness and Hebrew and tradition felt quite meaningful.

I had some qualms, ranging from the relatively small-scale request that all the actors standardize their pronunciation of the name “Moishe” to the more serious issue of the choice to include antisemitic slurs frequently with no content warning, but I generally felt that aspects of Jewishness were well-integrated and presented with nuance.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the show is its depiction of Ron Williams — a young man who had moved to the East End from Lancashire — and his descent into fascism. The show emphasizes the widespread struggle to find employment in the East End in the 1930s, and focuses on Ron’s growing frustration with this. The script explores the way in which his hopelessness and desperation make him susceptible to the propaganda of the BUF, who promise that they can support him in getting a job, and encourage him to believe that “English soil should be worked by English hands.” The depiction of a character who is originally likeable but who is swept up by dangerous belief systems is cleverly done, and offers a robust commentary on the recruitment techniques of many far right organizations which target disenfranchised young men and urge them to run with the idea that they are being systematically disadvantaged. And of course, while this is apt in the context of the 1930s political climate, it also felt upsettingly pertinent nearly 90 years later as we consider things like incel culture, far right extremism and the power of the internet in radicalizing citizens, particularly young men. It was a sensitive exploration of the subject, and provided quite chilling food for thought.

However, this exploration sat somewhat uncomfortably with the ending of the play, where all characters — many of whom had been violent and hateful towards one another throughout the show — essentially made amends and were friends again. On the one hand, it is important not to practise absolutism in these cases, and to make it clear that people who have done terrible things are not and should not consider themselves to be too far gone; there is always value in redemption and to treat people like a lost cause negates the possibility of change and progress. In this vein, seeing moments like this is incredibly impactful, sending a clear message that no matter how far down an alt-right pipeline one has travelled, there remains the option to turn back and do better. However, at the same time, watching the Jewish characters — particularly one upon whom Ron had personally inflicted an extreme physical attack — effectively holding hands and singing kumbaya with a violent fascist made me feel quite uneasy. It may have made for a lovely, neat ending, but it didn’t seem to do the characters or their situation justice.

If this production continues its run or moves to a more central venue — which I really hope it will do — I have every confidence that they will iron out the little issues of polish. If they were looking to make bigger changes, I would point towards the ending as something to reconsider – and while this may be ambitious as a late-stage edit, to end such a strong set of performances on an equally strong, as well as nuanced and thoughtful, message would be a wonderful way to improve. At its core, it is an uplifting performance by a very talented cast, and it tells a story that we absolutely all should hear, not only for its historical value, but also for the undeniable relevance it has for contemporary audiences.

“Cable Street” runs through March 16 at the Southwark Playhouse in London.