My Jewish education largely focused on Ashkenazi traditions, the Holocaust and Israel. I was involved in Hebrew school, Jewish summer camps and youth groups, yet my exposure to non-Ashkenazi perspectives came only in college, where I met Sephardic Jews and enrolled in Jewish Studies courses. This limited view left me unaware of Jewish communities beyond my own, let alone knowledgeable about Jewish languages beyond Yiddish.

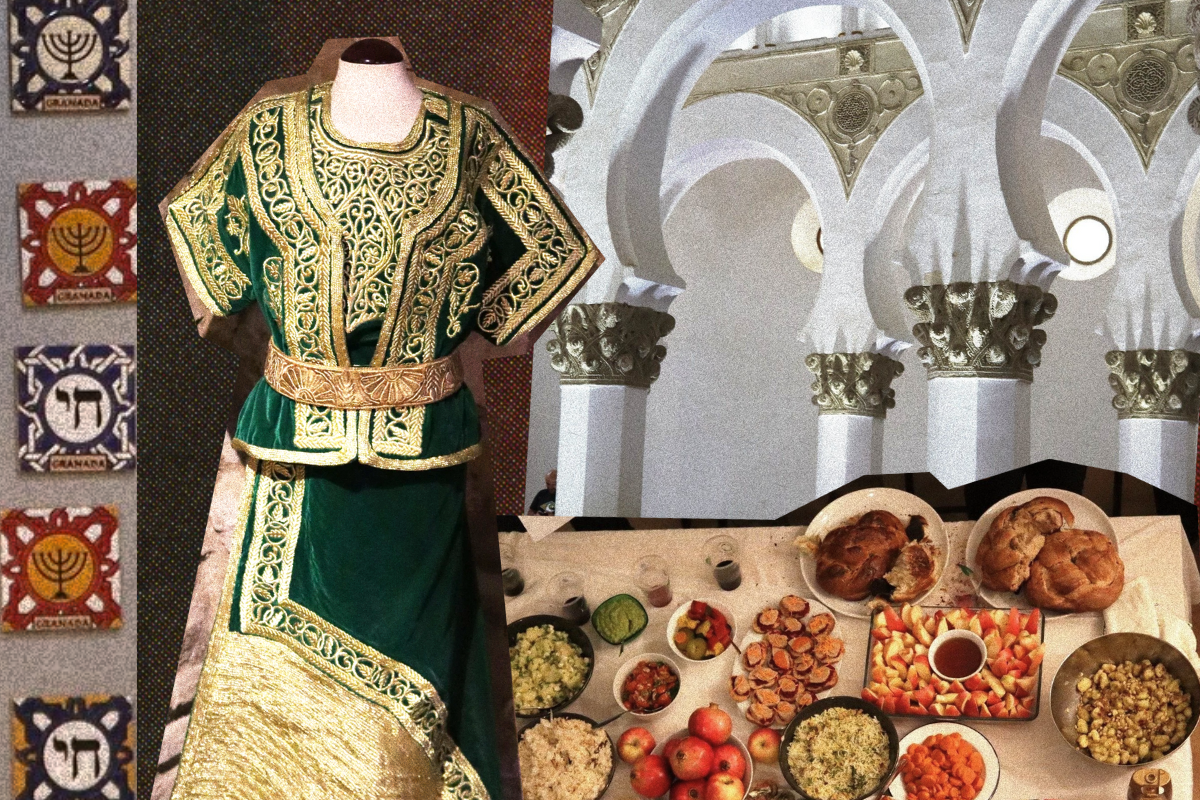

During a recent month-long reporting trip in Spain that was supported by the Pulitzer Center, however, I was reminded of the lapses in my education as I explored the implications of the 2015 Sephardic citizenship law, the history of conversos — Jews forced to convert to Catholicism — and the preservation of the Judeo-Spanish language, Ladino. While there, I was immersed in Spanish Jewish life, visiting Shabbat services in Madrid, Seville and Palma, celebrating Rosh Hashanah in Barcelona and Girona and attending an Oct. 7 commemoration event in Madrid.

As I explored Sephardic traditions, I found myself thinking back deeply on the narrow scope of my own Ashkenazi Jewish upbringing.

In the United States, the majority of what is thought of as Jewish culturally is Ashkenazi, from bagels and pastrami sandwiches to Yiddish phrases like “schlep” and “kvetch.” It’s a common misconception that all Jews look like Larry David or Adam Sandler.

It might be surprising to Americans, then, that the largest applicants to the 2015 citizenship law were not Jews in the U.S. or Israel, but those in Mexico, Colombia and Venezuela, who collectively put out nearly 63,000 applications. What’s more, the first Jews to arrive in America were actually Sephardim.

When I explained this Ashkenazi-centric outlook to my interviewees in Spain, some were perplexed. “Don’t Americans know about the Jews in Brazil and Peru?” one asked me.

Growing up, I certainly didn’t.

I remember learning about the Maccabees and why we dip apples in honey on Rosh Hashanah. But beyond an afterthought mention in a textbook, my Jewish education spent minimal time covering the Beta-Israel community of Ethiopia or Mizrahi Jews, those from the Middle East and North Africa who spoke everything from Arabic to Farsi and predominated countries like Iraq, Iran, Syria and Yemen.

To make sure my memory wasn’t failing me, I messaged some of my religious school classmates and camp friends, who confirmed they didn’t recall much nuance, either. “Everything we learned was through an Ashkenazi lens,” one told me.

To understand where Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions differ, look to Jewish history

These stereotypes make more sense when you consider that Ashkenazim make up roughly 70 to 80% of the Jewish population worldwide. This makeup is mirrored in the U.S., where two-thirds of Jews are Ashkenazi, while 3% describe themselves as Sephardic and 1% as Mizrahi. In Israel, though, more than half of the population is something other than Ashkenazi.

Sephardim is often used as an umbrella term to encompass all Jews outside of Ashkenazim, whether or not they have roots in Spain. This is quite misleading, as it overgeneralizes the differences between Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews across the Ottoman Empire, North Africa and the Middle East. In my reporting, I grappled with how to explain these differences to readers, in Jewish and general audiences. I found that Sephardic Judaism cannot be fully understood through an American lens, given the distinct historical differences between Sephardic and Ashkenazi communities.

For centuries, Jewish life flourished in the Iberian Peninsula, to the point that Toledo, the center of Spanish Jewish life in the Middle Ages, was known as Jerusalem West. That golden age declined amid 14th-century religious persecution and pogroms. Any remaining converted Jews left during King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I’s Spanish Inquisition were subject to the 1492 Alhambra Decree, which ordered the expulsion of those found practicing Judaism.

While the Ashkenazi community formed in relative isolation in Eastern Europe, the Sephardic experience primarily developed after these exiled Jews fled Spain and Portugal as they settled in North Africa, the Ottoman Empire and Latin America. Though my fieldwork took place in Spain, my reporting required me to speak with people from Seattle to New York and consider museum artifacts from Morocco and Turkey.

Moreover, while Ashkenazi Jews primarily interacted with Christian governments, Jews in 15th century Spain lived under Muslim rule. In some parts of the Iberian Peninsula, day-to-day Jewish life may have been closer to that of their neighboring Muslims than the Jews living in Eastern Europe at the time.

These differences translate into modern day liturgical expression. Unlike the Ashkenazi movement, which split into Orthodox, Conservative, Reform and Reconstructionist movements, Sephardic synagogue services are Orthodox or Modern Orthodox. Sephardic cantillation, the ritual chanting of prayer and response, involves more interactive chanting with congregants, as well as elements of melodic Arab maqam. In contrast to the Ashkenazi synagogue structure of chairs facing the bimah, Sephardic synagogues arrange seats around the room, facing the reading table as the center.

Today, Spain’s Jewish community is a patchwork composed of both traditional Sephardic and Reform communities, the latter generally founded by Ashkenazi expats. The only Jews who are Sephardic by origin are ones who moved back to Spain from other places or remained in Spain as conversos, those Jews forced to convert to Catholicism.

As a reporter, my work is strengthened when I consider multicultural perspectives

As a pale, visibly Ashkenazi woman, sources often asked what brought me to Spain. I was drawn to unpacking the nuances within a topic that often goes under-reported not just by media outlets, but within Jewish spaces. I have always felt deeply connected to the idea of Klal Yisrael, a Yiddish phrase meaning “the whole Jewish community,” and I let that value guide my approach to reporting. Despite the cultural barriers to reporting in a new place, the shared experiences of persecution and resilience across Jewish communities gave me cultural context for my reporting, even if my own family fled pogroms in Białystok instead of Seville.

When I returned home, I found myself repeatedly reflecting on Jewish diversity in my conversations with colleagues and friends. While Ashkenazi history and culture have become synonymous with Jews in the U.S., the Jewish experience is not monolithic.

My work as a reporter would have benefited from an education that reflected the plurality of languages, customs and traditions of Jews around the world. Take Central Asia’s Bukharan Jews, who spoke Judeo-Tajik in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, the Abayudaya community in Eastern Uganda or the Romaniote Jews, indigenous to Greece, who are arguably the oldest Jewish community in Europe. By leaving out these perspectives, Jewish organizations reinforce a narrative that minimizes Jews’ historical diversity and excludes Jews of Color.

Learning more about Judaism’s unique diaspora history didn’t just enrich my reporting, it deepened the connection I feel toward my religion. Embracing the full breadth of Jewish diversity doesn’t just benefit journalists, it strengthens our community as a whole.

Rachel Hale’s project, “Echoes of the Inquisition: The Descents of Spanish Inquisition Jews Reclaiming Their Sephardic Heritage,” primarily explores the implications of Spain’s 2015 Sephardic citizenship law, conversos, and the preservation of the Judeo-Spanish language, Ladino. Her work is funded through a Pulitzer Center grant.