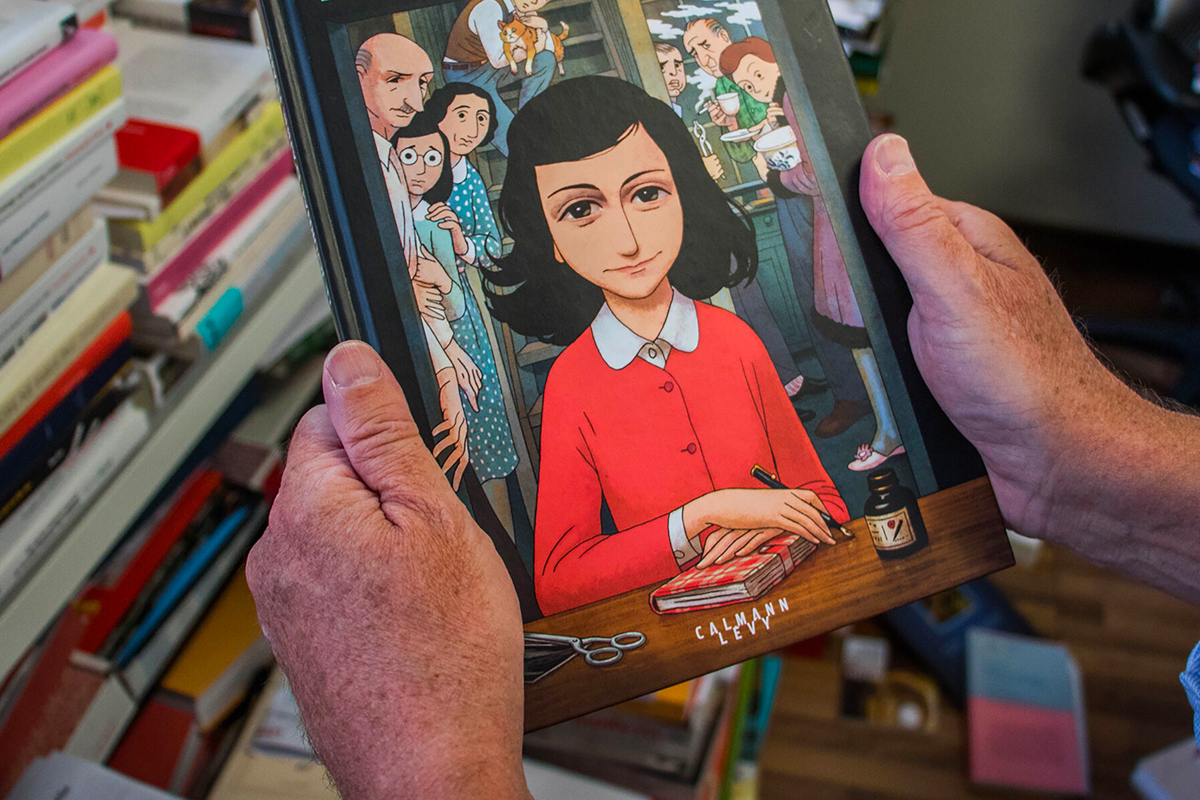

A teenage refugee who died of a curable disease 77 years ago is in the news yet again. This week, it’s because Keller Independent School District in Texas recently requested that an illustrated graphic adaptation of Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl” be removed from library shelves.

This is the second high-profile book restriction this year to impact Holocaust books. This January, the McMinn County School Board in Tennessee banned Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel “Maus.” And with each book ban, I’m reminded of my favorite memorial in my adopted home, Berlin.

Known as the Empty Library, the memorial marks where, on May 10th, 1933, students and Nazi party members set words on fire. They burned books that were considered “un-German” and subverted Nazi ideology. Works by Bertolt Brecht, Sigmund Freud, Erich Kaestner and others were destroyed.

Standing at the site today is an empty underground library, marked by several underground plaques adorned by a quote from Heinrich Heine, whose books were also burned: “That was only a prelude. There where books are burned, eventually people are burned, too.”

I return to that empty library mentally, and sometimes physically, each time another book ban is announced. This week’s removal of the illustrated version of “The Diary of Anne Frank” was a painful reminder that Holocaust stories (though not only those) are being stripped from libraries — and, notably, school libraries.

“The Diary of Anne Frank” and “Maus” are remarkable because they capture the personal, intimate human experience of a genocide, the Holocaust, that stripped humanity from Jews (and those the Nazis considered to be Jews). Their immediacy is why I, and other Holocaust educators, use them to teach.

Whether in a ghetto in Warsaw, a tenement in Berlin or a shtetl in today’s Romania, the pain and pleasure of daily life often continued in spite of persecution. Couples met and got married at Auschwitz. Sons were circumcised in secret. Children were smuggled into clandestine ghetto schools in hopes of a better future. Teenagers discovered their own bodies as well as those of their lovers. Women miscarried.

And yet these details, especially those relating to sex and sexuality, have been cited as reasons to ban Holocaust books such as “Maus” and “The Diary of Anne Frank.” It’s much easier to reduce the Holocaust to numbers, to highlight a timeline of antisemitic edicts and to list the names of camps and Nazi officials. Many alumni of Jewish day schools and Hebrew schools can recite these details because, for many years, this was how we remembered. Genocide itself is a difficult topic. Why must more human messiness, sex included, be brought into it?

I was reminded of this whilst reading Ariana Neumann’s “When Time Stopped: A Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains.” Neumann pieces together her father’s survivor story, a story that he refrained from telling her. In one moving section, Neumann questioned the nature of the relationship that her grandmother Ella had with the man she served in the concentration camp Terezin. Whether sexual in nature or not, her grandmother wrote about how this relationship helped her and her husband Otto survive longer.

I mention this because it’s part of the unsavory history of the Holocaust that many would rather forget or ignore. But when people censor Holocaust stories, whether of survivors or those murdered, because of their more human elements — sex, violence, self-discovery — we flatten real people’s stories and reduce their identity to their victimhood. This route risks focusing on the actions of the perpetrator rather than the lives of the persecuted.

The pedagogy of teaching the Holocaust has shifted in response to this realization: The discovery and recording of individuals’ stories is, in fact, what has guided numerous museums and organizations dedicated to telling the story of the Holocaust in recent years. From the USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem to the Arolsen Archives in Bad Arolsen, Germany, the emphasis on individual and familial narratives has transformed Holocaust research and education.

I’m relieved that the superintendent in Keller, Texas, expects the challenged books, including the illustrated “Diary of Anne Frank,” to return to shelves soon. When it does, I hope the reason for its removal is announced, too. With the impending start of the 2022-2023 academic year, it’s crucial that students have access to it. I fear, however, that it is only a matter of time until the next school removes Holocaust books.

Books are accessible in a way that professional Holocaust educators like me, who often work for museums and NGOs in larger cities, often aren’t. Though we do a lot, there are many things we cannot do. We cannot bring back those who died in the Holocaust. We cannot keep alive the remaining survivors. But we can fight so that libraries can include their stories in all their human vividness, warts and all. An empty library — or even an emptying library — is an act of historical distortion and censorship. Erasing the complicated parts won’t help us remember; it will doom us to forget.