As citizens of the world suffering a global pandemic in unison, we missed out on a lot of scheduled cultural moments for 2020: the Olympics in Tokyo, the pan-continental EuroCup, and that thing where it’s New Year’s Eve and you don’t want to go out but your friends are insisting on going to some shitty bar where you have to pay 75 bucks to get Busch Light spilled on you. Anyway, we missed out on some great stuff for sure, but perhaps the loss that hit us (see: me) the hardest was Eurovision 2020.

Eurovision is a cultural behemoth: the longest-running, annual, international, televised music competition — yes, Guinness knows — that has been cranking out otherworldly bangers for over 60 years. It’s given a platform to some of the greatest performers and songwriters our planet will ever know, and, just as importantly, some of the most delightfully weird shit you will ever see. Within that wide range of performances is Israel, a notable entrant as one of the few competing countries that is not, geographically, a part of Europe. Israel has a storied past with this event over the years, and has produced some notable winners.

The details of the competition’s structure are bonkers, but here’s what you need to know: Every participating country nominates a performer or group to represent them. The selection method varies from an American Idol-type thing, to bracket style competitions, to straight-up choosing someone.

Since 2015, Israel has selected its Eurovision performer though a reality TV contest called Hakochav Habah (The Next Star). There is an important distinction between a country’s chosen performer and its chosen song. While the show determines which lucky Israeli will represent the country in that year’s competition, the song itself is selected in an entirely different manner and is often not one of the performer’s own.

Which brings us to 2021, and the pure, unadulterated magic that is Eden Alene. Fresh off her 2020 Hakochav Habah victory, Alene was primed to dominate the Dutch stage and bring home the (beef) bacon. While we missed out on the actual competition, we’re lucky to have been gifted each country’s song selections as performed by their nominees. And while most of the world was understandably swooning over the masterclass in groove given by Icelandic nominee Daði og Gagnamagnið, I couldn’t stop listening to Eden Alene and thinking about the significance of her entry, “Feker Libi.”

Alene, 20, was born in Israel to Ethiopian Jewish immigrants belonging to the Beta Israel community who made aliyah during the mass asylum movement of the 1980s. The incorporation of Beta Israel Jews into Israel has not always been smooth. Issues of racism, systemic oppression, and rejection plague members of this community to this day. So, not only is Alene one of the youngest stars to ever compete for Israel in Eurovision, but she is also the first Israeli of Ethiopian descent to represent the country in the competition.

The value of this is being recognized nationwide, as Alene’s mother, Zehavah Varkanesh, noted in an interview with the Times of Israel: “Eden represents pride for all Ethiopians. Everyone is behind her, supporting her and loving her.” For a community of Jews who have struggled so long for recognition and acceptance, her ascent has the potential to be a monumental moment in Israel’s history. Alene herself is acutely aware of this. In her own words: “It is an insane honor to represent my country. It is amazing that an Ethiopian is doing it for the first time. Think about where we were when the Ethiopians first started making aliyah and look at where we are now. It’s a whole new world.”

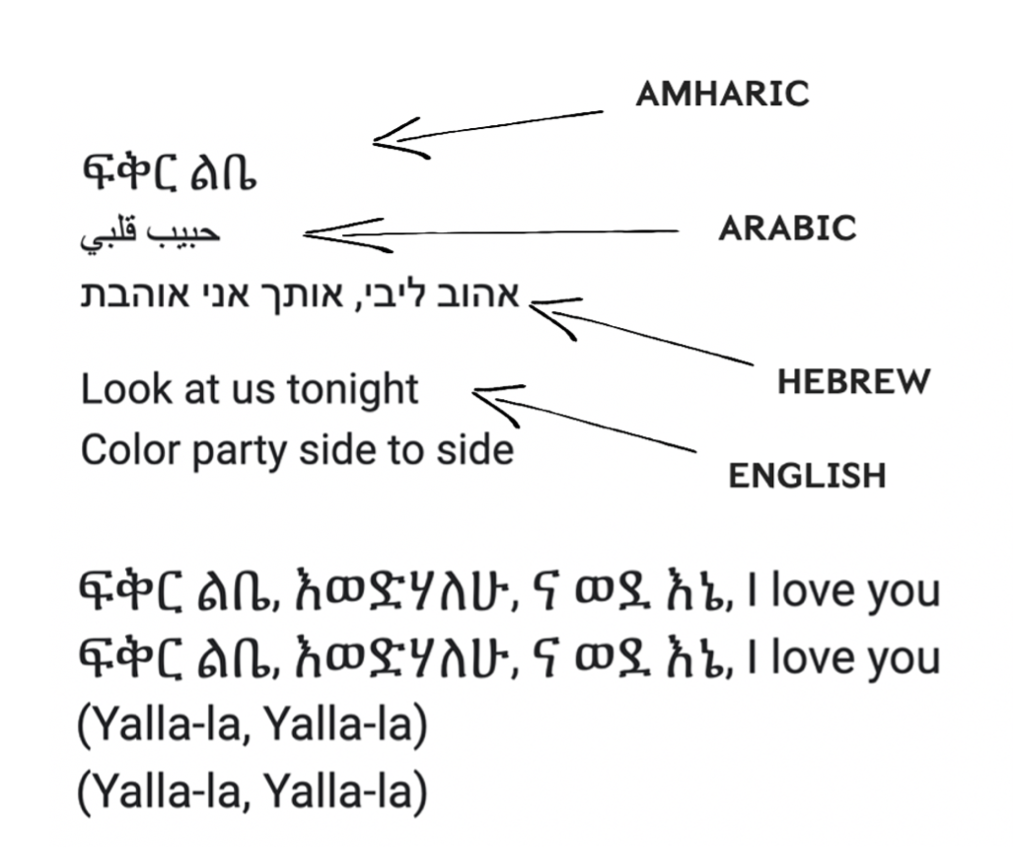

“Feker Libi,” Amharic for “My Beloved,” weaves a surface-level narrative of celebration and romantic positivity while delivering some pretty powerful subtext. Sure, her beloved could be referring to a real person. But if read through a geo-political lens, and with rotating lyrical lines written in four languages — Amharic, Arabic, Hebrew, and English — the tone of this piece feels quite different.

Alene sings that she loves this “person,” but perhaps it’s also a reference to Israel and Ethiopia. In the chorus, Alene sings: “Feker Libi / Tonight is our story / We celebrate the glory / We have no shame.” One could take this message and apply it almost literally anywhere in the Jewish diasporic canon; however, for me, I can’t help but think about Passover and the story we sit down to tell every year. Consider asking how this re-telling looks for a Beta Israel Jew, especially one who is now an Israeli. Consider the struggles this population has gone through in gaining acceptance and recognition of not just faith, but of genealogy and history.

In composition and performance, “Feker Libi” prominently features an Ethiopian instrument, the tom, a plucked lamellophone that makes its sound by plucking the end of a metal “tongue.” Belonging to the Anuak and Nuer groups, the tom is similar in construction and tone to the Shona “mbira” of Zimbabwe (you’ve heard this before; think of, like, every intro to a Lion King song). “Feker Libi” was co-written for Eden by Idan Raichel and Doron Medaliem, the latter also having worked on Netta’s 2018 Eurovision winner and kikar dance smash-hit “Toy.” In addition, Raichel, who has a personal relationship with the Beta Israel and Ethiopian Jewish musical practices, wrote this song very intentionally for Alene.

So now, in 2021, Alene is once again representing Israel in the competition *fingers crossed* post-COVID. But, in accordance with song eligibility rules, “Feker Libi” is ousted, and instead, “Set Me Free” was chosen as the winner out of three finalists. This song was co-written by Amit Mordechai, Ido Netzer, Noam Zaltin, and Ron Carmi, and Alene was not involved. Again, this is common, but it brings me to my next point. This broken millennial will try to put it in Gen Z terms: “Feker Libi” was endgame, and the conscious choice to move past this lyrical message and sonic statement to a song like “Set Me Free” is worth unpacking, no cap.

The significance of Alene performing the content in a tune like “Feker Libi” for an extensive international audience cannot be overstated. While Israel is no stranger to minority representation during this contest (see: 1993, 1998, and 2009), there is something especially powerful about an opportunity for this marginalized Black Jewish community in 2021.

I’ve spent the majority of my career doing research, primarily in Nigeria and Zimbabwe, with marginalized Black Jewish communities, engaging with them to understand how music is used as a tool for recognition, acceptance, and identity construction. So when I say Alene is literally living the dream? I mean it. The most common sentiment expressed to me — especially by Black Jewish musicians from the Igbo Jewish community in Abuja, Nigeria — is precisely that. As Zadok Fancy, an Igbo Jewish rapper, once told me, “I want to sing for the Jews. I want to sing for the Black people.”

Which finally brings us to “Set Me Free.” Of course, it’s not Israel’s fault Eurovision 2020 was cancelled. I am giddy at the (re-)selection of Alene to represent Israel again, but I can’t help feeling a little let down by the song selection. “Set Me Free” is a fine pop song, possibly a great one, but the disjunct between musical content and lyrics, especially in comparison to “Feker Libi” for 2020, is a disappointment.

In “Set Me Free,” Alene sings about the dynamics of coming out of an abusive relationship, eventually breaking free and surviving: “Feeling like I’m in prison, looking for the reason I don’t wanna say goodbye / Used to be your treasure, now I’m gone forever.”

An important message, for sure, but not a new one. Throw a stone at any country’s pop charts and you’re likely to find a dance-tastic anthem about shitty exes and power dynamics. In a competition like this with the largest international platform any artist can access, one really has to consider what is worth saying, and how it is said. But hey, at least we can consider ourselves lucky that “La La Love” — which came in second to “Set Me Free” or “Feker Libi” — lost, because, well…

‘Cause love is my disease I don’t need no medication

I-I-I I want it to infect my generation

Party ’till the mornin ‘Till the sun is glowing

All I wanna do is La la la la la love

Yiiikes. And don’t get me started on Germany’s entry for this year…

I know it might be hard for Americans to fully grasp the cultural value and impact Eurovision has, but with almost twice the viewership of the Super Bowl, it’s big. The social currency alone generated by an artist or country’s success is immense. So, how does Israel factor into all of this? The competition is not just a chance to showcase musical content and ability but, moreover, an opportunity to learn, educate, and connect.

Like many sporting events, Eurovision changes location every year, but with a twist: the winning country gets to host the competition the next year. For Israel, winning means more than just bragging rights. It’s an opportunity for peace and allyship. To critics who would call this naive, I would simply say: listen. Listen to what is being sung every year. Listen to the crowds cheer and encourage other countries. Listen to the discourse around the competition every year. You will see tangible evidence of grassroots transnational community strengthening through music.

As Israel and its rabbinate begin to recognize more Jews around the world, especially those marginalized and of color, I look forward to more musically diverse and rich entries from Israel in the future. Music plays such an important and informed role within subaltern communities and the way their identities are constructed. The formation of musical cultures from those identities, based on lived experiences, is the beating heart of Eurovision. Every year, no matter where it’s held, Eurovision connects a diverse community of individuals who create magic through music night after night by making their voices heard.