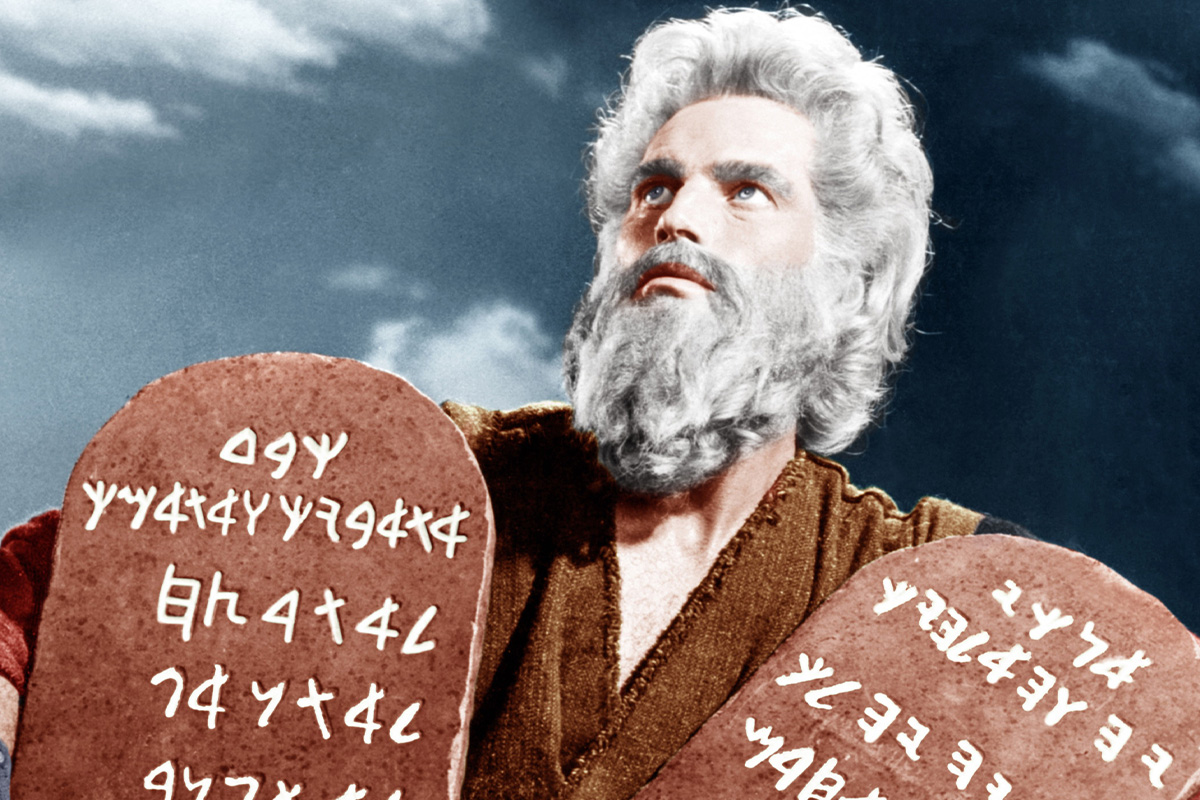

Since I was 5 years old, I remember gathering with my family every year before the beginning of Passover and watching “The Ten Commandments” on cable television. It was my first real introduction to the story of the Exodus. The first time, my eyes lit up in wonder as I watched Charlton-Heston-as-Moses perform miracles on the screen — it seemed like this man could do anything, from turning water into blood to parting the sea to speaking to God through a burning bush.

As a couple of years passed by and watching the film became an annual tradition, I began to find similar wonder in the movie’s more tangential storylines. I obsessed over Anne Baxter’s Nefertiri’s elaborate gowns and ever-charming demeanor. I teetered at the edge of my seat when Lilia (Debra Paget) falls into Dathan’s (Edward G. Robinson) grasp. I cried as Moses finally reunited with his mother, Yochabel (Martha Scott). All of these storylines were, to me, just as much the heart of the movie as Moses standing atop Mount Sinai.

So imagine my disappointment when, at 8 years old, I found out in Hebrew school that none of these events are true to the Exodus story in the Bible, with some of these characters not in there at all. There is no mention of Nefertiri in the original biblical story, Lilia is purely fictional and the circumstances behind the harrowing reunion between Moses and his mother were just the writers’ imagination.

As I looked further into the film and compared it with what I knew to be biblically accurate, I found that its departures from the text were endless. While I understand that art often necessitates originality, these deviations made me curious. Why does this Jewish story, already filled with so many heart-wrenching and dramatic twists and turns, need exaggerating? And which of its aspects did the filmmakers think were lacking?

As I progressed into adolescence, I began to notice that the movie incorporated many of its own additions of femininity into the story, found in two principal forms: the mother and the temptress. Motherhood is represented by Bithia and Yochabel, whose love for Moses spills out in powerful but often melodramatic scenes. Meanwhile, Lilia’s and Nefertiri’s sexual appeal serves as their defining characteristic. And of course, Zipporah (Yvonne De Carlo) strikes a balance between these two categories of womanhood, increasing her status as the ideal woman for the epic’s protagonist.

I’ve grappled with the film’s takes on femininity for a while. While extending the role of women in this story may add some important layers to it, boxing them into two narrow categories diminishes the impact that they can possibly have. The filmmakers’ need to add sexuality to the story is also a bit off-putting, since it gives the movie that classic Hollywood appeal at the cost of distracting viewers from the core storyline.

The film’s diminishment of biblical figures goes far beyond women, unfortunately. Both Moses and Ramses (Yul Brynner) are designed as your typical comic book heroes and villains, chiseled-chinned and muscular and constantly making grand declarations in bellowing voices. In some moments, the film practically elevates Moses to the status of a Greek God, which somewhat contradicts the main point of the narrative.

All these points considered, there is certainly merit to the criticism that the movie takes all of the Jewishness out of the Jewish origin story. Even very basic aspects of the film, such as the anglicization of all the characters’ names or the fact that the cast was majority non-Jewish, add to this feeling of dissociation with the story’s Jewish core.

However, in utilizing so many dramatic techniques and breathing new life into a centuries-old story, it is undeniable that the filmmakers put an incredible amount of effort into conveying the Exodus to a mass audience. Even the movie’s 13 million dollar budget (over 138 million when adjusted for inflation) illustrates just how much work was put into casting, production, set design, costumes and special effects. And it worked. The movie successfully drew in a massive audience. It made people from all walks of life sympathize with the plight and triumph of the Jewish nation, whether they realized it or not. It is unlikely that this result would have occurred had the creators stuck to the biblical script.

With all of this in mind, I feel like I’ve finally come to terms with my opinion on the film that made up such a big part of my childhood Passover tradition: Although I may cringe a bit as Nefertiri cries out, “Oh Moses, oh Moses!” I can still appreciate the effort put into it. Despite its inaccuracies and exaggerations, it is still an epic depiction of my own origin story. And pretty darn fun to watch.

Late Take is a series on Alma where we revisit Jewish pop culture of the past for no reason, other than the fact that we can’t stop thinking about it?? If you have a pitch for this column, please e-mail submissions@heyalma.com with “Late Take” in the subject line.