Yet again, it feels like Antifa is on everyone’s lips. The president recently tweeted that he would designate it a terrorist organization — despite the fact that Antifa is not actually one cohesive organization but an umbrella term for the movement against fascism — and everyone from politicians to celebrities to your Aunt Dina has an opinion on the matter.

So let me share mine: I am an anti-fascist Jew in Britain, and when those in power publicly bash grassroots justice movements like Black Lives Matter or Antifa, I look to history to ground me in a line of tradition. It reminds me that I am not the first to fight for a more just world, that my forebears in this movement would have been familiar to me and in community with me.

Anti-fascism has long been a part of Jewish heritage, from the outsized proportion of Jews who volunteered to fight the fascists in the Spanish Civil War to the Young Communist League in Manchester who organized against the British Union of Fascism in the 1930s. But these days, I’ve been thinking most about the British, Jewish, and anti-fascist 43 Group.

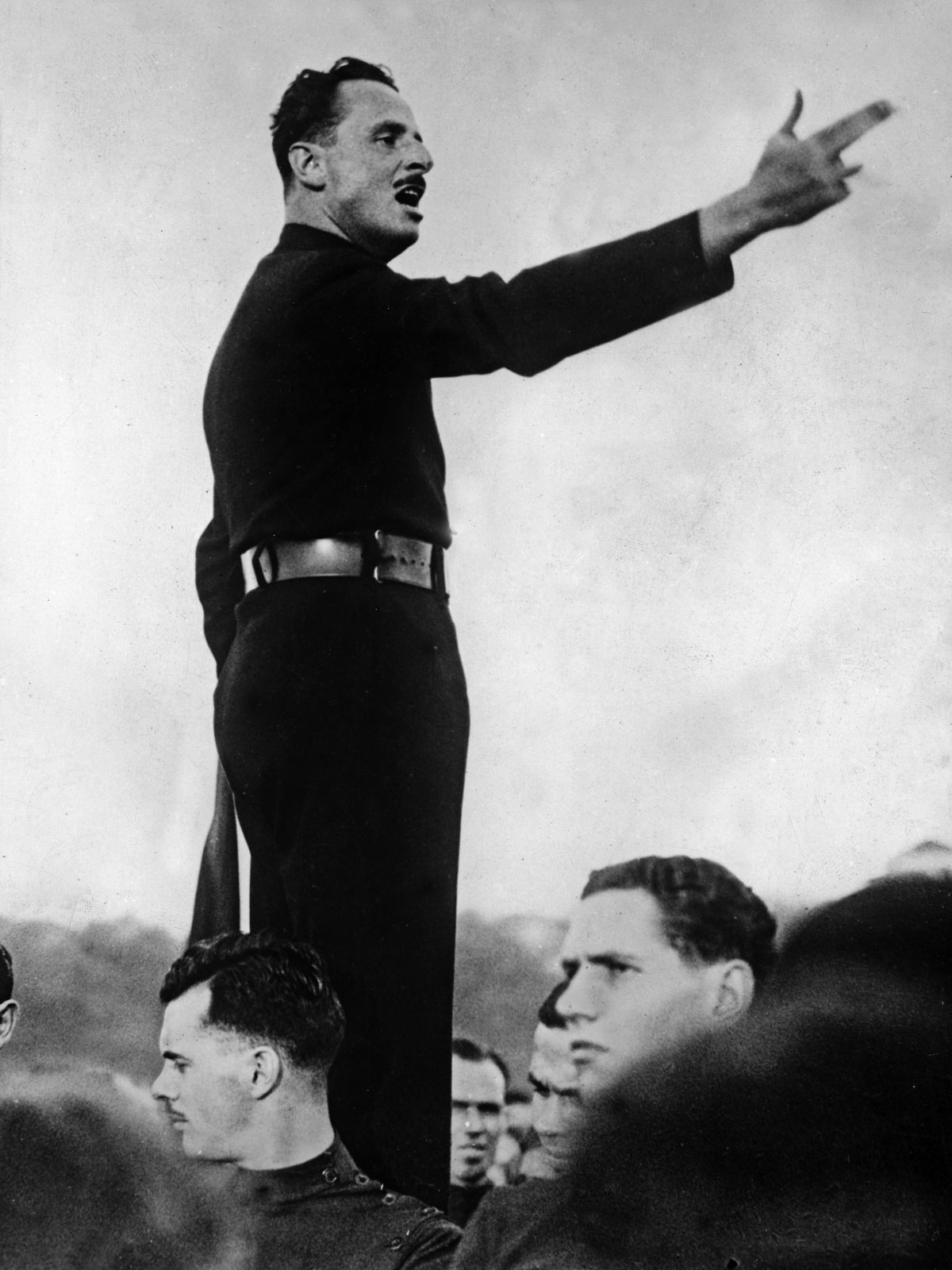

After the end of World War II, it seemed that fascism would struggle to regain any kind of foothold in the United Kingdom. Oswald Mosley, a prominent fascist politician, had been put under house arrest and the country was filled with nationalistic energy that seemed to despise everything Germany had stood for. Unfortunately, a UK government program called Defense Regulation 18B that jailed fascists and Nazis and interned them together throughout the war resulted in the movement growing stronger. Instead of putting a stop to UK fascism, it functioned like a petri dish for white supremacy and anti-Semitism.

After the war, the far-right continued to organize and speak publicly, spreading anti-immigrant and anti-Jewish messages. There were weekly fascist rallies in Ridley Road Market in Hackney, a predominantly Jewish neighborhood in East London. In fact, by 1946 there were as many as 40 weekly fascist meetings and rallies taking place in the city every week. Many areas of East London were known to be unsafe for Jews; simply walking there could mean running into a fascist group and being beaten up.

In April 1946, 43 Jewish ex-servicemen gathered at Maccabi House, a north London Jewish community center and sports club, and vowed to fight the rising fascist threat, even if it meant using violence. This was the birth of the 43 Group. They were revolutionary radicals who had seen the horrors of the Shoah with their own eyes and would stop at nothing to prevent that evil from gaining power at home. They would regularly heckle fascist meetings, physically remove speakers from spouting hate, and sabotaged the fascists by placing undercover agents in their organization.

I look at Britain in 2020 and see the far right growing in popularity. Last year, Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, known as Tommy Robinson, who is a far-right nationalist hate group leader, ran to be an independent member of European Parliament. His campaign slipped his flyers through my door where the mezuzah hung outside. He and his English Defense League were back in my area just today. As I write this, masses of white supremacists are giving Nazi salutes and singing nationalist songs at the Winston Churchill statue in London. This threat is real and it is way too close for comfort. When I am tempted to feel fear and hopelessness, though, I remember the anti-fascists who came before me. They walked this path first and we can learn from them.

The first important thing to remember is that the government did not help the members of the 43 Group, so they took on the burden themselves. They tried to go to the liberal Labour government who were sympathetic, but in the end, did nothing to address the regular beatings and rallies in Jewish neighborhoods. The Board of Deputies of British Jews’ attitude toward the rallies was “turn the other cheek,” according to members of the 43 Group. They had to take matters into their own hands.

But they also didn’t fight alone, joining together with other marginalized people. After two years of fascists marching through Jewish neighborhoods and beating and terrorizing residents, Jewish and Irish workers joined forces and attacked a fascist rally resulting in what is now known as The Battle of Cable Street.

The impact of the 43 Group is debated, but they were able to significantly infiltrate and disrupt the activities of the fascists and they disbanded voluntarily once they believed the immediate threat of a fascist resurgence had passed. It’s important to remember this group’s aim was to protect their community from an urgent threat; their ambitions were less grandiose and they were successful in derailing fascist activity in London.

And then, when other groups were at risk, they re-formed to fight again. While the original movement disbanded in 1950, former member Harry Bidney formed a new group he called the 62 Group to fight old and new fascist organizations who, at that point in 1962, were targeting Black and minority, ethnic immigrants.

The work of the 43 Group did not end in 1950, and it did not end in the ‘60s — it continues to this day. Everyone who stands up against racist, fascist hate groups and protects the people they target is part of this tradition. When Black, POC, LGBTQA, and immigrants are threatened, so are all Jews, especially those who also fall into one of those categories as well. As a community, we have the responsibility to stand up to the rise of the far-right and pray with our feet, our voices, our bodies.

There is so much more incredible information about the 43 Group available online, if you want to learn more I recommend the book We Fight Fascists: The 43 Group and Their Forgotten Battle for Post-War Britain by Daniel Sonabend and this short documentary which includes interviews with members of the group.

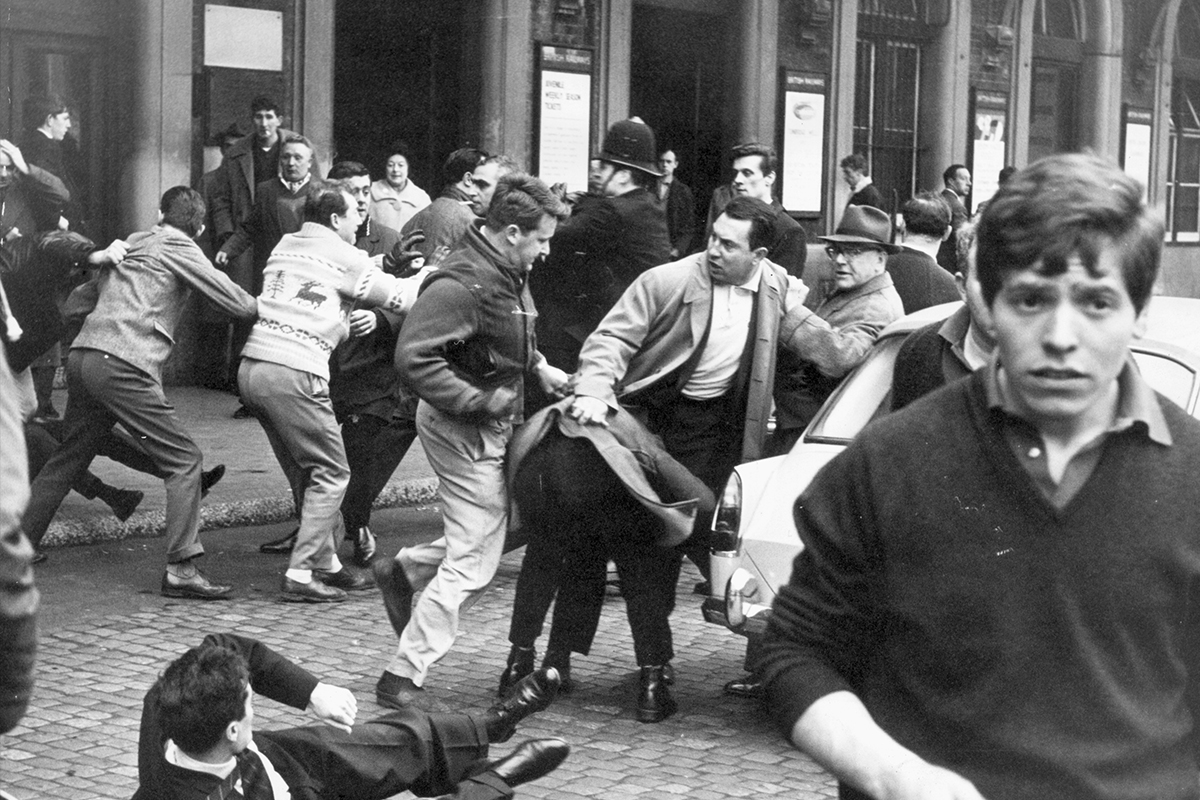

Header image: A fight breaks out between anti-Fascists and supporters of Oswald Mosley’s Union Movement in the forecourt of Charing Cross Station in London, 12th May 1963. Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.