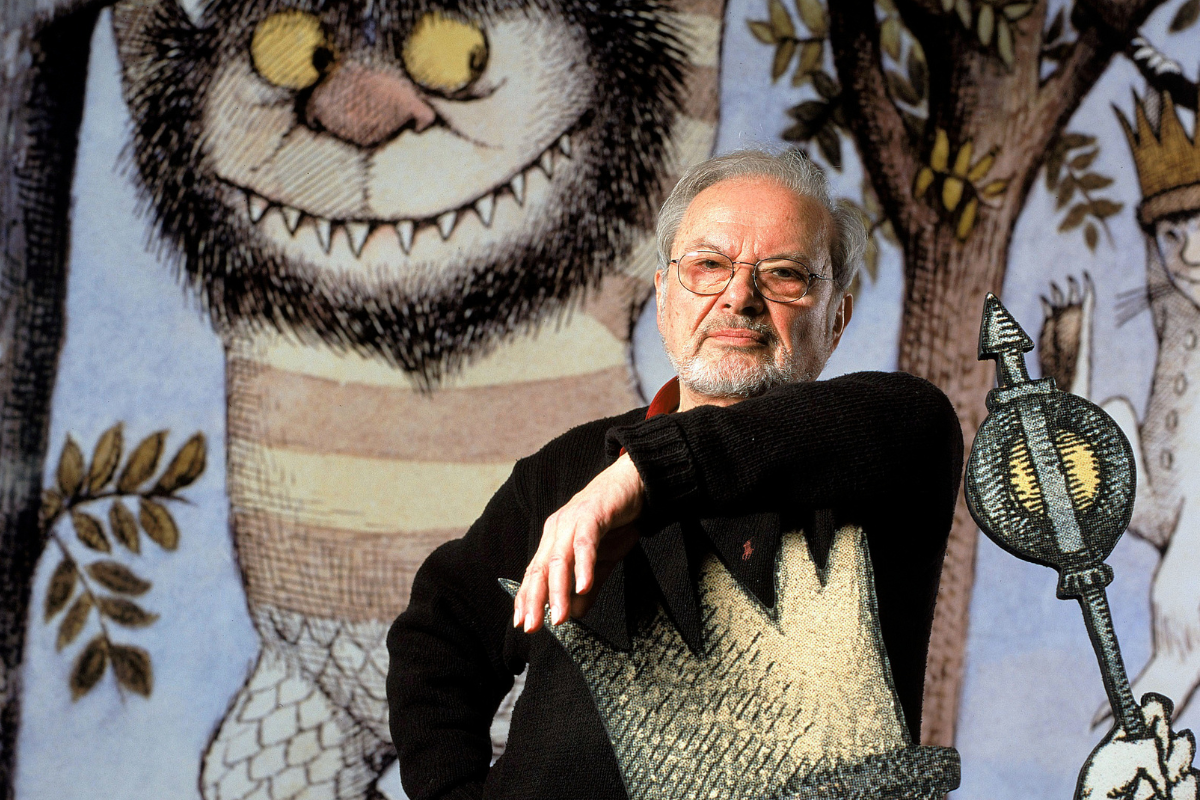

Maurice Sendak, the celebrated creator of the iconic picture book “Where the Wild Things Are,” was queer, Jewish and a bit of a wild card himself.

Born June 10, 1928, Sendak was the third child of Polish Jewish immigrant parents, Sadie (née Schindler) and Philip Sendak, after his beloved siblings, Natalie and Jack Sendak. As a poor kid from Brooklyn, Sendak grew up in a precarious time. Not only did he have to deal with the physical vulnerabilities of childhood — he was often so sick as a child with various illnesses that his grandmother dressed him in all white to disguise him as an angel to prevent the Angel of Death from taking him too early — but he struggled with the mental and spiritual ones as well.

Living through the Great Depression, Sendak’s family often teetered on the edge of poverty, moving from apartment to apartment while his parents (both non-fluent in English, which in any decade can make functioning and surviving in America trickier) struggled to find steady work. In the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust, several of Sendak’s relatives from Poland died, leaving their surviving relatives in Brooklyn grieving and haunted.

And if that wasn’t enough already, Sendak was also teased by the children in his neighborhood. In a 1976 interview with Rolling Stone, he said: “I couldn’t play stoopball terrific, I couldn’t skate great. I stayed home and drew pictures. You know what they all thought of me: sissy Maurice Sendak…” Sendak lived through the intense homophobia of the 20th century, and never came out as gay to his parents.

But throughout all his struggles, Sendak’s imagination acted as an escape.

From his sick bed as a child, Sendak would glance out the window, imagining different stories for the characters who lived on the everyday streets of Brooklyn. Maurice had his first taste of collaborative storytelling with his big brother Jack, as he drew pictures for the stories Jack wrote. His big sister, Natalie, who often schlepped him from place to place, also introduced him to many of the creative sources that would go on to inspire him as a professional artist, from Mickey Mouse to the opera.

As an adult, Sendak maintained his rich imagination, providing his young characters the same emotional layers of depth he saw in himself as a child trying to survive the world.

When Sendak found Ursula Nordstrom, a revolutionary queer publisher and the editor-in-chief of children’s books at what was then Harper & Row Books, it was a perfect match. Nordstrom wanted to create what she liked to call “Good books for bad children,” and Sendak’s work fit the description. Neither Nordstrom nor Sendak wanted to read or write books that painted childhood as some happy-go-lucky illusion where lessons were learned didactically — “See Jane run,” etc. — or where children were “perfect” bland figures without any faults. Books that spoke to the realities of being young and angry and hurt and scared — to the shadows that disturbed him as a young artist and the light he found in spite of them — were the stories that interested Sendak and his publisher.

Sendak worked hard to portray children in an honest light, using his own experiences as the framework for his stories. In 2011, he spoke to Pamela Paul for the New York Times and told her, “I developed characters who were like me as a child, like the children I knew growing up in Brooklyn — we were wild creatures. So to me, Max is a normal child, a little beast, just as we are all little beasts.”

And for this book about a beastly kid, he found inspiration for the title in the Yiddish words of his mother. He said she would chase after him and call him “vilde chaye,” translating from Yiddish to English as “wild animal” or “wild thing.” Thus “Where the Wild Things Are” was born.

Throughout his life, Sendak’s Yiddishkeit heritage and queer identity informed his work and his career. Themes of ostracization, monstrosity and survival permeated his work. Whether it was mentoring other LGBTQ+ and Jewish talents like Brian Selznick or his love for the spooky and supernatural — inherited from the Jewish folktales his immigrant father told him as a child — or simply living with the love of his life, Dr. Eugene Glynn, Maurice Sendak lived his life with a deep Jewish and queer sensibility,

In a conversation with Nuwer for South Carolina Review in 1984, Sendak said simply: “Art is an exploration of yourself. If it’s good art, then it’s also an exploration for other people.” Many queer and Jewish readers have Maurice Sendak to thank for creating a book — and a whole body of work — where we could take part in that exploration and find our own wild selves.