When Atlantic articles about single women without children in their 30s started landing on my proverbial desk, I took a long hard look in the mirror and asked myself if I was ready to keep living an “unconventional” life with so few models out there for women like me—“child-free,” nearing my 40s, and single. We were at once a phenomenon, mystery, and problem to solve.

Without marriage and children as milestones, how would we know what it meant to be “all grown up”?

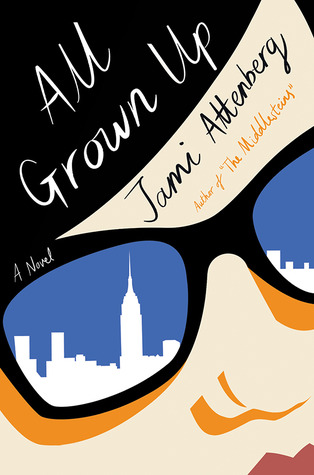

Cue the brilliance of All Grown Up by novelist Jami Attenberg, who seemed to rummage through the trenches of thoughts and feelings I never knew I had about the “polemic” posed by women like me. Reading this novel, I was both horrified and comforted to recognize parts of myself in Attenberg’s protagonist, Andrea, a single Jewish woman without children nearing her 40th birthday as the novel unfolds.

An art school dropout who negotiates relationships with a complicated, overbearing mother as activist and father as jazz musician and drug addict, Andrea spends a great deal of her time seeking sex and love in New York City while attempting to make peace with the fact that she doesn’t paint anymore, works on autopilot at a job she doesn’t even care enough about to hate, and hasn’t yet grieved her father’s overdose and death years ago.

In the spirit of Sheila Levine of Sheila Levine is Dead and Living in New York City, I read this slim novel with deep empathy for Andrea as part of a tribe of women who master the art of loneliness while still attempting to show up for life—first dates, office presentations, family events, parties. We live with crushing and impossible expectations to perform fertility, marriage, and motherhood, but have little proof that these decisions actually make women happy or fulfilled.

Case in point: “Indigo Has A Baby,” the chapter about the moment when Andrea’s friendship with her best friend Indigo shifts due to impending motherhood. Women are supposed to be joyful and congratulatory toward our pregnant friends, but we also know that motherhood hijacks women—and our relationships with those friends will never be the same. Yet, it’s a taboo so few women want to admit or address.

With vivid certainty and hilarity, Andrea describes this dynamic: “It’s not that I don’t care about seeing her baby, it’s that I don’t care about seeing any baby. Also, I know what will happen. I have been down this road before.”

Andrea avoids seeing Indigo and her infant until she’s pressured through a series of text messages to show up. She admits, “What will happen after I see the baby is that Indigo will become exceedingly busy with her life for a very long time. Say, five years or so. Then she will have time to see me. Then she will desperately need to see me.” Through Andrea, Attenberg utters what so many of us feel but never say—that we’re experiencing our friends’ foray into parenting in complicated, ineffable ways.

Andrea finally makes it to Indigo’s meditative, blissed out nest of breastfeeding, tears, and tea, but not before she has an emergency visit with her therapist, cataloging a series of failed sexual encounters with random men. “If you add them all up, they equal a boyfriend,” Andrea argues to her therapist.

Indigo and Andrea remain sealed off in two completely different bubbles of experience, failing to fully comprehend the other. There’s Indigo, shrouded in layers of flowing fabric, a baby attached to her nipple, and then there’s Andrea, her eyes brimming with tears post-therapy session, trying to be a connected and engaged friend. “People architect new lives all the time,” Andrea thinks to herself.

Attenberg continues to drop dazzling revelation and insightful humor throughout All Grown Up as Andrea tries to figure out what it means to be an adult. The subject of babies—as symbols of life or doom—is a taut thread plucked throughout the novel.

Entrenched in her singularity, Andrea boldly tells a new lover with children from a previous marriage that she “doesn’t like kids that much.” Her best friend Indigo has a healthy, fat baby but faces the eventual unraveling of her nascent marriage to a rich, aloof husband, sending enlightened Indigo spiraling down a tunnel of self-centered despair.

Andrea’s sister-in-law Greta, once a vivacious young editor in love with David, Andrea’s rock-n-roll older brother, gives birth to a baby with complications. The couple moves to New Hampshire in an attempt to stabilize and raise their baby together. Much to Andrea’s dismay, her mom follows to fortify against the madness, but Greta falls apart and David throws himself into a state of creative self-exile to stay sane. Meanwhile, Andrea dreads leaving NYC to visit, and Sigrid, the baby, “fails to thrive.” Instead, the baby stagnates, withers away over five years, and eventually dies.

Sick babies are another taboo that most women won’t talk about, at least publically, yet Attenberg handles it with searing honesty and grace. Sometimes having a child is nightmarish, horrifying and totally defeating, and this, too, is parenthood. And sometimes being the family witness to all of this can be just as exhausting and depleting but in ways that can’t be spoken. Doing so triggers questions about boundaries, personal autonomy, and tapping into the empathy well when it seems to have run dry in your direction.

Andrea confesses, “I always reel for a few days after I witness someone’s personal truth. I walk around feeling like I’m wearing their essence like a tight sweater. With Greta, it’s a wetsuit. It takes a week until I can finally peel her off me, but I wake up one morning, naked in the apartment, and it’s all me again, and she’s gone. No more Greta, I think. No more sick babies, no more sad brothers, no more lost mothers. They’re there and I’m here. I’m free.”

Yes. This book calls freedom itself into question. Women without children crave autonomy and singularity but we also long for deep connections that require us to surrender to the complications and vulnerabilities of relationships that tax our status. We wish we could be alone, together. Andrea acknowledges, “I miss them [her family] so goddamn much, and if I don’t see them again soon, touch them and talk to them, I’ll never survive this life.”

Attenberg’s terse, fine-tuned, luminous writing operates at the highest frequency, teasing out the barbarity and beauty of being human. Andrea, with all her imperfections and anxieties, has gathered a unique stockpile of wisdom from her perch at the farthest edges of feminism, and as a reader, I want to meet her there and listen to everything she has to say. She speaks for so many of us, revealing feelings we never knew we had, and recognizing this is proof enough that we’re all grown up.

Top image via Flickr/Helena Perez García