“There was a time when I felt maybe I shouldn’t be writing this novel,” Ayelet Gundar-Goshen tells me over the phone from her home in Israel. “Maybe it’s irresponsible for me, as a woman and as a mother of a young girl, to be writing this novel.”

“This novel” Gundar-Goshen is referring to is The Liar, which tells the story of a young girl in Tel Aviv who falsely accuses a past-his-prime Israeli musician of sexual assault. It brings up ugly questions about the #MeToo movement, about false accusations of sexual assault, and about believing woman. Gundar-Goshen struggled with “writing this novel about a girl making up a sexual assault, when that’s the most frequent argument of predators,” she explained. Ultimately, only around 2% of sexual assault allegations are false, and around 63% of actual assaults go unreported.

Ultimately, she decided to write The Liar. Why? “No one would tell a man he can’t write a story about a pedophile, or would tell a man that you can’t write about a male murderer. No one would tell you you can’t write about a man doing bad things because people might think that all men are murderers and pedophiles. But when it comes to a woman, people are very fast to assume that when you talk about one woman, you talk about all women.” Gundar-Goshen added, “That’s a chauvinistic perspective. And I don’t want to limit myself because of the fear that people who already look at the world through a chauvinistic perspective will continue doing it through my novel.”

In a conversation with Alma, we talked about the #MeToo movement, how The Liar was received in Israel versus how she thinks it will be received in the U.S., and how, spoiler alert, everybody lies.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

What inspired you to write this story?

The inspiration is based on a real story. A friend of mine is a public defense attorney, and we had this lunch when she [showed up] really excited. She was representing a migrant, an illegal migrant, who was charged by an Israeli woman of sexually assaulting her. And, for a while, it seemed like she’s the victim, and then my friend managed to prove that this woman made up the story about the sexual assault. She came to lunch very excited about that because they managed to release the guy; he was supposed to go to prison and then suddenly he was released! She kept talking about the woman who made up the story, calling her a monster and a psychopath.

When I heard this story, I thought: Maybe it’s too easy to call a woman like that a monster. It’s much more interesting, and much more difficult, to try to understand what makes a person make up such a story. I was really haunted by this question. After this lunch, I started thinking about it, and it wouldn’t let go of me, this question of what makes a woman do such a thing? What if she’s not a psychopath, what if she’s not a monster? What if something just happened and then the words took a liberty of their own, and she just wasn’t able to stop it? That how The Liar, the novel, was created.

In an interview you did when the book came out in Israel, you said, “To me, to tell a woman what is permitted or forbidden to write, to say to a woman, ‘Do not write about a liar because men may use it against women’ — this is a repressive act in itself.” Can you expand on this?

It was a very important point for me to make. I strongly support the #MeToo movement. Being a mother of a young girl, I think #MeToo is such a great thing for her, to be born in a time when acts that were very much permitted during the time when I grew up are no longer permitted. My little girl is 5 years old now, and maybe when she’s 16, she won’t go through the stuff that I went through when I was a 16-year-old girl walking the streets of Tel Aviv. It wasn’t a very safe environment to grow up in. The idea of men finally having to pay a price for sexual assault, for sexual harassment, I think it’s a wonderful thing.

I had a male journalist, an Israeli male journalist, telling me: “You shouldn’t have published this novel this year. You should’ve waited. Because this is the #MeToo year, and you don’t want to be undermining #MeToo.” And I thought, seriously?! Now I have a male journalist telling me what a woman should and shouldn’t write about.

What has the #MeToo movement been like in Israel?

I don’t think it’s had the same impact as it had in America. I wish it had. It did have a strong impact here; I feel it changed a lot in Israeli society, [but] it wasn’t as effective as it is in the U.S. because Israel is still a much more chauvinistic and, in a way, racist society than in the U.S. People say things here that you would be very quickly fired for in America. Here they say it, the next day they apologize, and the following day they’re just doing the same job that they did earlier.

What do you hope readers take away from your book about rape culture at large?

I feel in every book, not just in The Liar, my biggest wish is that the reader — instead of judging the character about what she’s doing — will ask himself, “Could I be the one doing this thing?” So for me, it’s not about judging the character, saying this woman is a psychopath or a monster. It’s to say: Could I, under some certain circumstances, be caught in a lie? Maybe not this specific lie, but another lie? And what happens when I lie? Because everybody lies! And how do I deal with truth which is too impossible to bear? Do I sometimes twist reality, because I just can’t handle it as it is? For me, it was about the readers asking themselves questions about their own lies, rather than judging this woman about her lie.

Also, I thought [with] #MeToo being such an important movement, I do feel that sometimes we shift from saying “we don’t believe women” and “women are manipulative liars” — which was the way people thought about women’s complaints before #MeToo — to saying “I believe all women no matter what.” And I think that’s a very strong shift. Being a human being, I know people can do everything. And even though I do believe the majority of women, I do think that some women do make up these cases. And now we’re saying those who make up cases either don’t exist, and if they do, they’re monsters, they’re not part of human society, they’re crazy, they’re lunatics. And I don’t like that. I think it’s too easy.

Obviously this book largely focuses on one big lie, but there are a lot of lies going on — pretty much every character is enwrapped in some kind of lie at some point.

When I wrote it, I thought about every person in the street, every person in my family, every dearest friend, I [asked] myself: What is it that she would lie about? What is it that this person would be capable of lying about? While I wrote the novel, I thought: I want to know each one of the characters, the moment in her life when she chooses not to tell the truth because sometimes those moments are much more interesting to explore, and have much more psychological depth in them, than the moments where people just say what’s really happened.

What was the translation process like? Translating from Hebrew to English, do you work closely with the translator?

Because I’m not a native speaker, and I don’t read literature in English, I can’t really judge the quality of the translation. It’s a very difficult process of letting go and realizing I have no way of really knowing what’s going on there. With The Liar, we had a residency of translators. We had seven [come] to Jerusalem and work on the translation together, which was quite amazing to see the way each one gets the novel. And, you know, trying to get it to a foreign audience that doesn’t always know the nuance of Israeli culture, it’s a challenge.

Does The Liar feel different than your other novels, Waking Lions and One Night, Markovitch?

I think in all the novels, the motivation was always the same: It’s taking characters who are doing something [where] our immediate response, our immediate judgement towards this character, would be to say, “This is a terrible person.” And then through the power of literature, trying to unfold…

It’s like this sentence by Yehuda Amichai, the Israeli poet. He has a line from one of his poems saying, “The fist used to be an open hand with fingers.” I think it’s one of the most beautiful lines in Hebrew literature, in Hebrew poetry. This is what [I’m] trying to do: To look at a fist and to try to imagine how it used to be an open hand with fingers, and what happened to make the fingers clutch into a fist. I always meet my characters when the fists are ready to hit. We meet the girl [in The Liar] when she’s making this terrible lie, just like in Waking Lions, we met the doctor after he was ready to leave the refugee on the side of the road. The novel is trying to look at the fist, and to [ask], what happened to this open hand? Could this hand, which is now a fist, re-open and become an open hand once again?

I love that idea. What do you hope readers take away from The Liar?

It’s about looking with eyes wide open, not just about the characters, but about ourselves. And asking ourselves about this very delicate relationship between lies and truth in our life. On one hand, we all hate liars. To lie is such a heavy social crime, and to call somebody a liar is a very serious insult. I mean, somebody can be stupid and we’ll still like him, can be clumsy and we’ll still like him. But if somebody is a liar, then he’s automatically an outcast. How can it be lying is such a heavy social crime, but then again something that everybody does? So I really hope the readers will look at this very delicate embroidery of lies and truth, not just in the lives of the characters, but also in their own lives.

The Liar is released September 24, 2019.

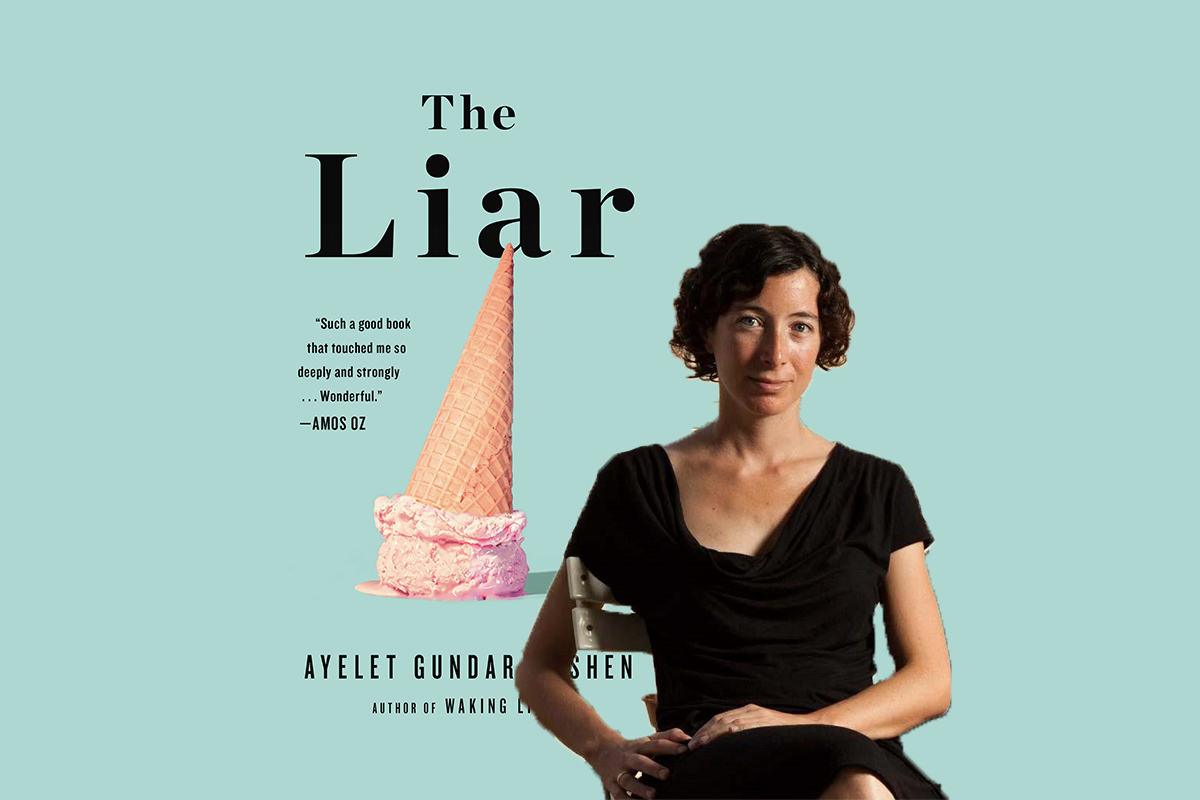

Image of Ayelet Gundar-Goshen in header by Nir Kafri.