My name is Katherine Bogen, and I am a 25-year-old, bisexual, radical Ashkenazi Jewess. I’m white. I do yoga, take voice lessons, and am semi-regularly compared to a “Disney Princess.” In high school, I was a (mostly!) straight-A student. When I graduated college, I was awarded the honor of “outstanding undergraduate.” Now, I am a published researcher in violence prevention.

And last Tuesday night, I was arrested by state police for disorderly conduct. I do not regret it — not for a moment. Let me tell you why.

The Wyatt Detention Center in Central Falls, Rhode Island is an intimidating exhibit. Coiled wire sits menacingly atop a chain fence. The bland aesthetic — brick, beige, grey — displays material finality. Police cruisers rumble by, gravel crunching beneath wide tires. The officers inside collaborate with ICE to detain immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. When the crunch gets louder — when the cruisers assemble — it means there is “trouble” afoot. Protesters. Activists. “Social justice warriors.” And now, Jews.

News of the conditions within these detention centers has swept the nation. Conditions have been called “egregious” and invoke human rights abuses in our global political memory. Abuses like apartheid and Japanese internment and, yes, the Holocaust.

As a researcher in violence prevention, I relate this process to my work. We have a saying in the field: A first date with a domestic abuser doesn’t start with a punch in the face. Processes of normalized violence are gradual. First, the perpetrator may blame the victim for anger and disappointment, creating a scapegoat for ensuing conflict. Next, the perpetrator isolates individuals from their loved ones. Third, violence increases in severity, as perpetrators feel emboldened. Eventually, victims are stripped of their humanity. Sometimes, the abuse ends in death.

Nazi-occupied Europe followed a similar pattern of escalating abuse against Jews, and we must not ignore the fact that in present-day United States, we’re witnessing a similar crescendo of violence against migrants. Don’t believe me? Look at the signs.

Scapegoating: Donald Trump’s rhetoric about immigrants being rapists, drug dealers, and lazy cheats.

Fear-mongering: Migrants will hurt your women and steal your jobs! Your intimate and economic lives are at risk! No one is safe!

Isolation: The early strategy of deportation shifts toward detainment. First, in detention centers presumed to have basic necessities. Then, in overcrowded centers without food, clean clothing, or soap.

Violence: As news trickles through the cracks of these facilities, we learn about the processes of degradation in these camps. Women are sexually harassed, subjected to what some have called “psychological warfare.” Guards are caught referring to detainees as “scum buckets.” Border patrol agents joke about migrant deaths.

Hitler would have loved this.

We are bearing witness to state-sanctioned violence, on a massive scale, against an identified and intentionally targeted “other,” abused largely out of public eye. As I take all of this in, I am acutely aware of the position of privilege I occupy as a white woman, and therefore feel an especially strong call to put myself and my body on the line. Because I am able to participate in a stand-off with the state that is unlikely to cause me irreparable trauma. I am able to interact with police officers without credible threat of unlawful harm or battery. I am able to attend protests without fearing deportation. Essentially, when I engage in civil disobedience, I am allowed access to my full agency and humanity. I am allowed to consent to my own arrest. I am allowed to do so with the knowledge and confidence that such an arrest will not end with my assault, indefinite detention, or death.

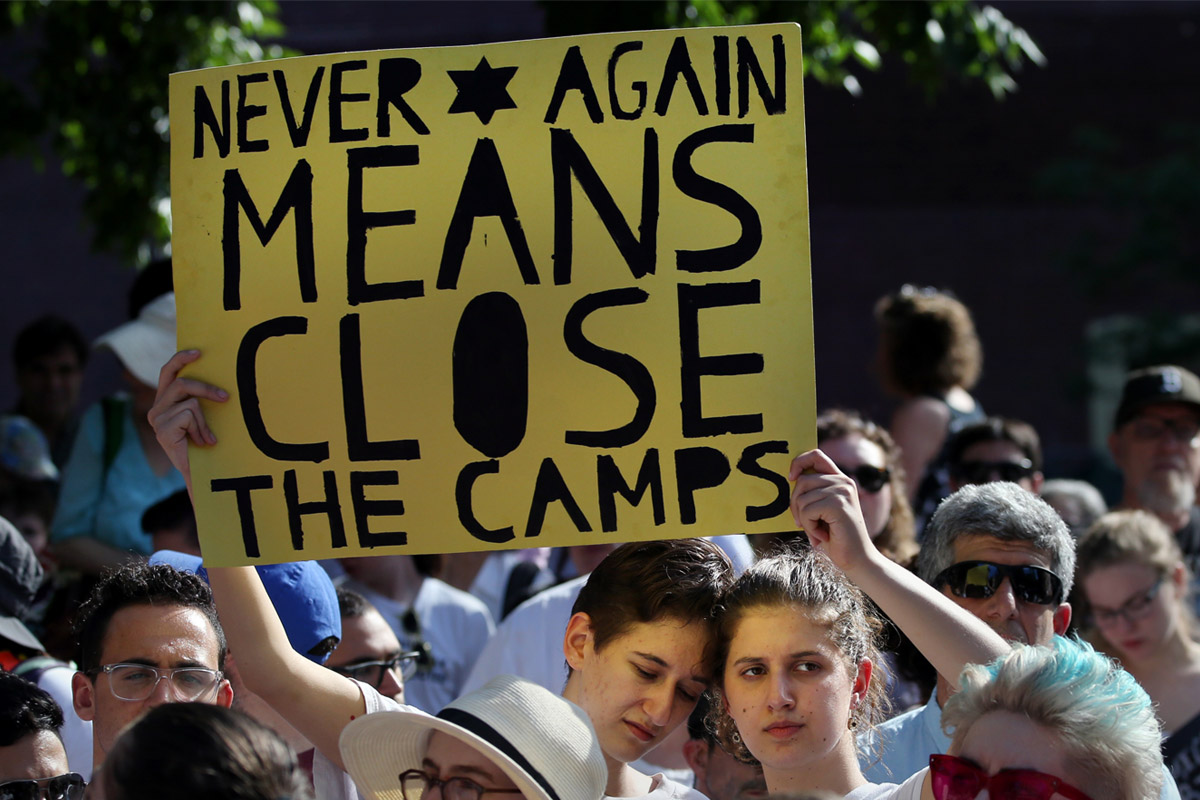

And so, last Tuesday, I stood outside of Wyatt Detention Center in solidarity with the detained. From 6:45-8:45, I was part of a group of Jewish and allied people who refused to allow the center to function as usual. The institution responded as institutions do — with repression. We were arrested, as we suspected we might be, 15 minutes before the detention facility was slated to close.

When I was led to the squad car, an officer offered to turn on the air conditioner to make me comfortable. He asked about my life and family. As I sang quietly to myself in my holding cell, another officer walked by and complimented my singing voice. While my record was added to the system, the officer typing in my misdemeanor asked about my work, and we discussed our experiences advocating for domestic abuse survivors. When I got my mugshot taken, I made a small joke about the unflattering photo. The officers photographing and fingerprinting our group insisted that it was a good picture, even zooming in on the screen to show me. In all, I was at the station for under three hours. By the end of the evening, local police were laughing genially about the absurdity of our group’s arrest. When I was released, one of them told me to get home safely, and reminded me that they were “just doing their jobs.”

Throughout the night, I found myself increasingly and disturbingly grateful to be white. The officers got to know me, offered me compliments and comfort, and tried to get me out of the station as quickly as possible. I am starkly aware that people who do not look like me would not have received the treatment that I did at that station. I acknowledge that people of color in the United States face interactions with police fearing their own execution. I acknowledge that guards do not compliment immigration detainees’ singing voices. They hurl insults, torment, brutalize, and mock. This experience was undeniable, galvanizing proof that I have a moral obligation to use my privilege in this struggle. I will absolutely continue to do so.

Jews are a people who can intimately recognize the warning signs for genocide, because, thanks to oral tradition, our history has been passed down from great-aunts and grandparents and loved ones who only narrowly escaped mass-extinction themselves. We can recite the gripping stories of their trauma in our sleep. We were raised on them, sitting in rapt attention at the feet of our elders, who doled out narratives of their pain as a clear warning of what happens when good people witness horror and choose to do nothing. Last Tuesday, 18 of us were charged with disorderly conduct because we refused to do nothing.

And this I promise: Our conduct will remain disorderly until these camps have been reduced to rubble and the detainees have been liberated. We must abolish ICE, terminate these camps, and provide trauma-informed care to detainees, to mitigate the frightening truth that our complicity has a rising body count.

Because adhering to the historic social “order” is what brings us Nazi Germany and children clinging desperately to their fathers as they both drown in raging rivers. I can see the arms of Oscar Alberto Martinez’s 2-year-old daughter around his neck, as the pair lie face-down in shallow water of the Rio Grande, 2019. And I can still see the bony elbows of my ancestors, malnourished, their sunken eyes peering helplessly out of faded photographs from Poland, 1942. And, like my grandfather’s sweet Hebrew in my ear, and my great aunt Helen’s snap-crackle Yiddish, I can hear the promise we made — a promise I intend to keep: Never again. Not for anyone.

Image by Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images