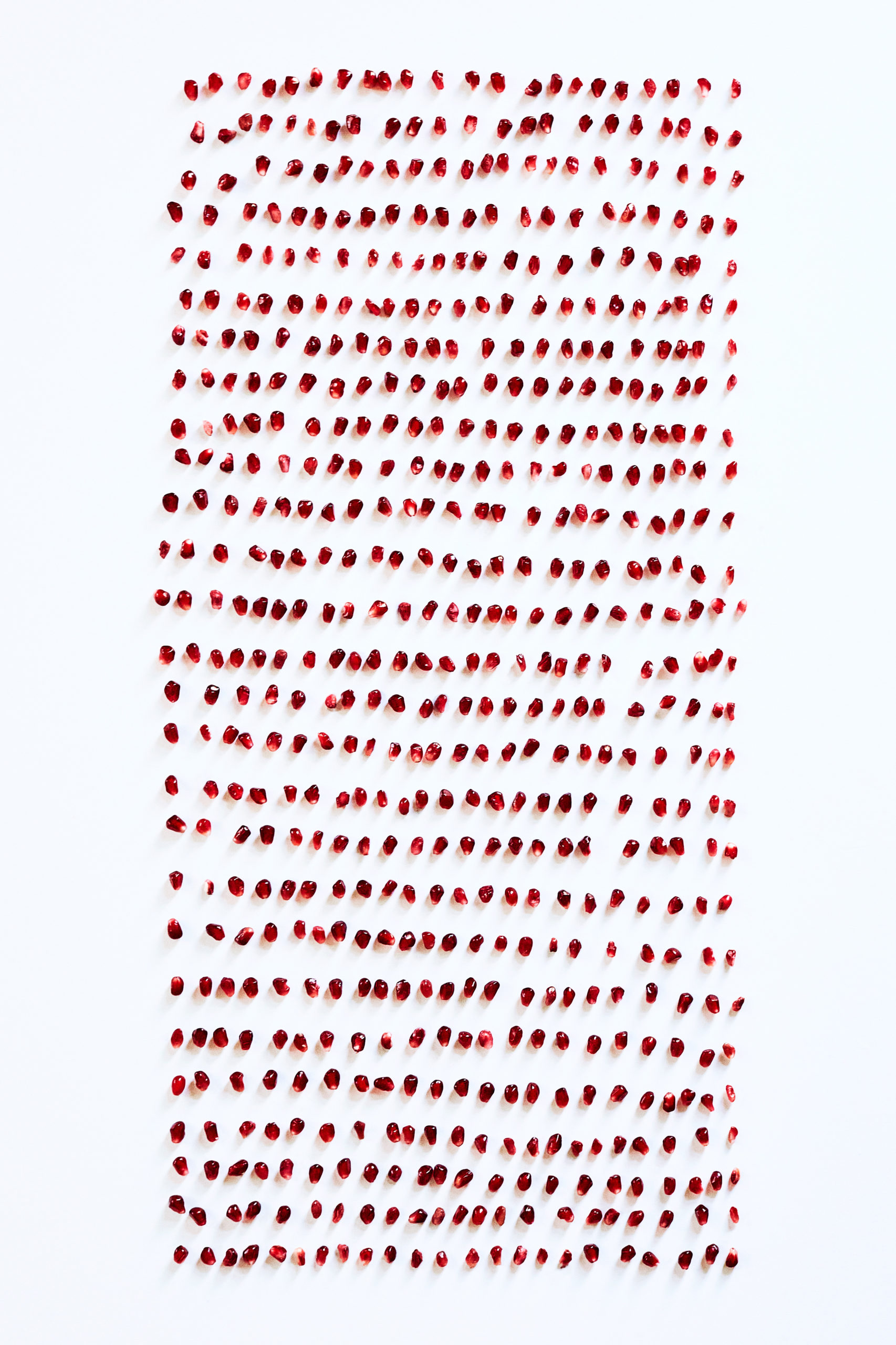

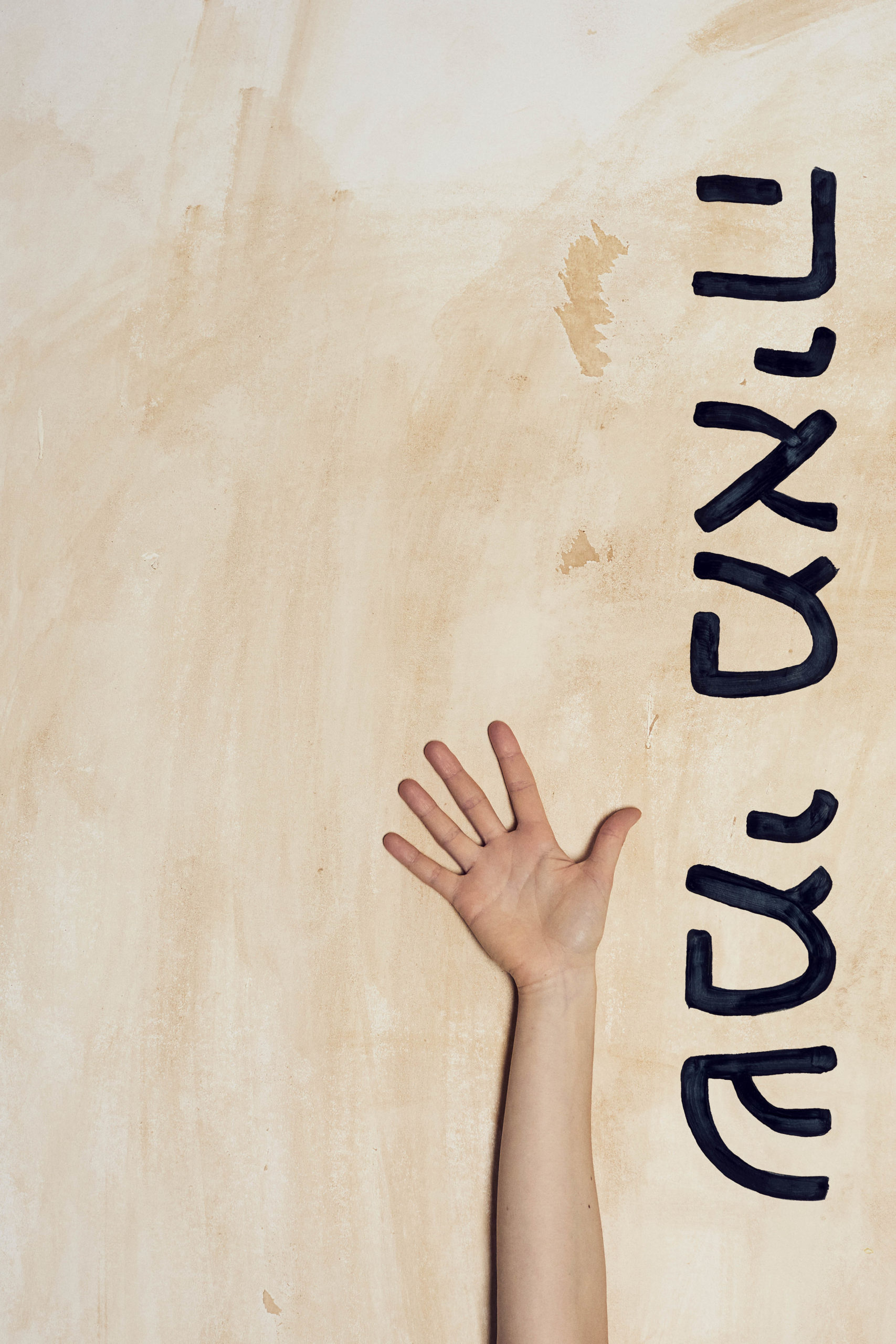

In some of the photographs that make up Manon Ouimet’s series “My Name Is Maya,” the everyday objects of Jewish ritual take on an unearthly, transcendent quality. Two coppery yads (Torah pointers) gleam against total blackness as their fingers touch. Exactly 613 pomegranate seeds are arranged in lines on a white background to resemble a piece of modern art. Buttery light and shadow superimposed on dense foliage make the world of “Golden Arc” (2021) feel totally unlike our own.

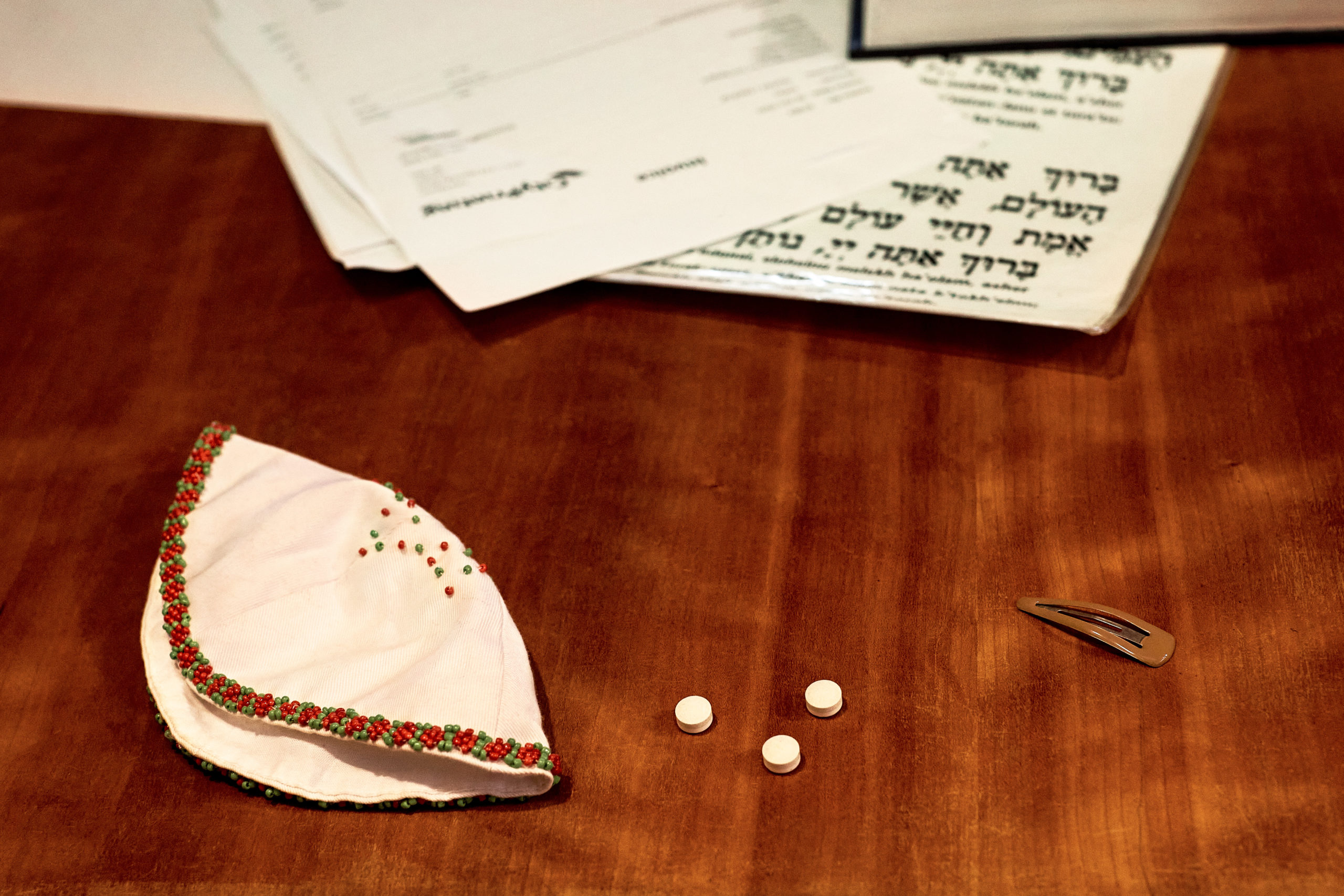

But in others, the British photographer seems to remind us that Judaism can be mundane, and can’t cure all of life’s woes after all. “Bimah Detail” (2020) features a folded, beaded kippah, three round white pills and a brown barrette. Ouimet has written a caption to accompany the image. “She still gets sick. Still gets heartache. Nothing three pills can’t shake.” And “Eternal Light” may be ironically titled: It shows four light switches labeled “Ner Tamid,” “Ark,” “Spots” and “Choir.”

“My Name Is Maya” documents Manon’s conversion to Judaism, which began in 2020; she marks each stage of the process in chronological order. The series was supported by an Arts Council England grant, and is on display at the Belfast Exposed Gallery through October 30, when it will move to Manon’s synagogue, Finchley Progressive in London. In the photobook that’s part of the project, she recounts that the seed for her conversion was first planted in 2009, when she was 19 and living in Sydney. She became friends “with a social circle that was predominantly Jewish, attracted to their sense of family, generosity and regular Friday night Shabbat dinners. The atmosphere with these friends was always warm and rooted me at a time that may have otherwise felt isolating, providing me with a familial strength that enabled me to flourish during my time there. Returning to London at the age of 25, I felt a loss of what I can only now describe as Jewishness. Life back in the UK was progressing, but something was missing…”

A few years later, she met Jacob, her Jewish partner. “As our relationship developed, we discussed a Jewish life together, but the idea of converting to a Jewish future came from me. I felt drawn to raising Jewish children, providing that same sense of closeness that comforted me.” When it became clear, in March 2020, that everyone would suddenly have time on their hands, Ouimet saw “a rare and great opportunity to truly immerse and educate myself, plunging into the year-long conversion process, albeit remotely.”

I spoke to Manon about converting during a pandemic, why she chose Maya as her Hebrew name, and some of her favorite images from Judaism.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Tell me about your family history. What is your background, where did you grow up, where are your parents from?

I was baptized by my British mother and my French-Canadian father. I grew up in southwest London as an only child. My mother had a small contained family who lived in Cornwall, while my father’s family was larger than life, based in Canada and the USA.

I have juxtaposing memories of Christmas; one year I would be surrounded by several joyous sugar-high kids and a dozen wild whiskey’d adults, blanketed in snow and submerged in temperatures that reached below -30 Celsius. And midnight mass with my grandmother “Nonnie” was always a mystifying experience. The next year, back in drizzly London, I would yearn for my big family and the noise that accompanied it whilst we celebrated in our somewhat isolated fête-a-trois. Religion played some role in our family, but it didn’t tend to involve me. I remember through a fog of incense pluming from the thurible, occasional visits to Church at Christmas and Easter.

When did you start taking photographs?

I started out taking portraits seven or so years ago, quickly realizing that photography, for me, is a vehicle through which to explore my relationship with what it means to be human — be it through others as the subject, or, occasionally, turning the camera onto myself. I got my Masters at the University of West England where I made my award-winning project ALTERED, a series that focused on people who have been subject to life-altering body changes. My work explores identity and visual representation and aims to find optimistic and courageous ways of celebrating the individual.

Tell me about your conversion journey. Who helped along the way?

My journey began during the height of the first COVID-19 lockdown in the U.K., a strange time to start the process of converting, but pertinent in a period where community and connectivity were physically lost and all the more desired. Week to week, I joined the Finchley Progressive Synagogue (FPS), delving into Judaism classes and Friday night Shabbat services online with such love and awe and a hunger to be firmly ingrained in their wonderful community. FPS is led by the earthy, wise and spiritual Rabbi Rebecca Birk. I can’t imagine what the conversion journey would have been like if I had been guided by someone else. It goes without saying that Jacob and his family were pertinent to my journey. They were there for me intellectually and emotionally and also joined me throughout the creative process, collaborating as well as supporting me.

My fellow travelers that were converting alongside me throughout the program have been a rock. Through this process we have learned, cried and laughed together and most of all they have been a solid reminder that it is anyone’s right who connects to Judaism to join the religion. We may not have been born into it, but converting teaches a depth of beauty that is unique to us who have chosen its path.

There was plenty of literature that supported me through the journey, too; Sarah Hurwitz’s book, “Here All Along,” really stood out to me for its generous relatability.

I see you work a lot with double exposure and superimposition throughout the series. How do you make those images, and can you describe what that practice means to you?

The metaphoric meaning behind the long exposures in this series is to capture the sense of morphing and change. Long exposures are made by the shutter being deployed for a longer period of time than is traditional, meaning that more light is captured by the camera — in this case, for many seconds.

To be specific about my technique, I held my face in a position to ensure part-sharpness in the image, before moving around to create the twinship of definition and blur. This, for me, indicates both a sense of starting a journey and then moving to an unknown place, all told in a single frame.

Double exposures and superimpositions provide a different narrative from the long exposures. When choosing to create them for this project, I was looking to build a picture of evolving heritage, layering narratives of past, present and future, each stage just as defined and relevant as any other. In contrast to the emotionally in-flux long exposure images, the double exposures and superimpositions are defined and cerebral.

Did anything about the conversion process surprise you?

The past year has been full of new and brilliant experiences. As part of the conversion process, one is expected to live a full Jewish calendar year, delving deep into studies, festivals and really living a Jewish life.

What caught me off guard was the encouragement to make Judaism my own. Liberal Judaism examines the Torah through the lens of contemporary life, constantly shifting to respond to modern life. I found that both unexpected and incredibly exciting as I felt myself not only joining a people, but also feeling heard by my new community about my personal relationship with these values, tailoring a connection that is truly authentic to myself.

Did you have a favorite stage of conversion? A ritual that felt particularly meaningful?

I was recently reflecting on a written diary I kept from the start of my conversion which notates my changing Jewish status. The diary is mostly concerned with reflections on whether I felt more or less like a fraud when taking part in Friday night Shabbat services and the prayers that accompany its commencement. Fluctuating self-reports, but a clear demonstration of confidence emerges throughout the pages. Every stage of the conversion was filled with learning and self-reflection. No moment was greater than another. It was just a living, breathing experience. Every festival brings its own wonderful ritual with an abundance of meaning.

But I feel very attuned to tashlich. It offers a sense of relief from the past year and an acknowledgement of responsibility and intention for the year to come, a grounding ritual. And then there is Shabbat which marks the week with meaning — it is the heart of every Jewish home. Shabbat is a palace of time, different from all other days, a mini Jewish festival at the end of every week. It is a time to connect to one’s roots, a communal spiritual gathering punctuated by food and family, songs, blessings, candles, wine and challah; what’s not to love?!

What made you choose the Hebrew name Maya?

An essential decision of the conversion process is that of choosing a Hebrew name.

How do I choose a name?, I thought to myself. By the way it sounds? By the way it makes me feel? For its meaning? Does it reflect back to me who I think I am?

In my contemplative moments, I think to the ocean, to a lake, to a large body of water and I stand still in my mind’s eye. Water brings me to the present and reminds me of who I am. I am one person in a sea of millions, just trying to feel the soil beneath me. Maya resonated with me as it shares the same root word as Mayim, meaning water in Hebrew.

What were the origins of this photographic project?

As part of my conversion, I was asked to produce two essays, which, as a photographer, got me thinking. With Rabbi Rebecca Birk’s blessing, I embarked on a visual exploration of my personal account of my journey through conversion and into the Jewish way of life. This photographic process gave me the opportunity to connect with Judaism in a way that made me comfortable to ask questions and find visual metaphors. The photo essay was honest and pure and naturally led me to think about the possibility of extending the work and making it public.

As someone who works visually, are there any images from Judaism or Jewish biblical stories that stick in your mind?

The Babylonian Talmud was a huge inspiration for the book I created for this project. I was struck by its design, each page artfully laid out, holding the opinions of various commentators to a central theme. I love the typography and paragraphing techniques — it is so distinctive and feels so Jewish. In designing the exhibit’s book with John Perlmutter, my father-in-law (as I said, Jacob and his family collaborated with me a lot on this project), I, wanted to pay homage to these layout techniques and create a reading experience that was aligned with the artifacts that inspire me.

The idea of Jews around the world conducting spiritual rituals is hugely moving to me. During Hanukkah, Jews light hanukkiyahs, all the same amount of candles; during Pesach, we dab red wine symbolizing the Ten Plagues; during Yom Kippur, we fast simultaneously, the 25-hour period meaning that at some point, united, we all overlap. The image of this togetherness, to me, is deeply beautiful.

Who were your visual references for this project?

Irving Penn’s still lives lived within me during my compositions. His use of simplicity, color and consideration helped me think about the layout and poise of each object. Edward Weston’s personified objects in his still lives, too, informed my photograph of matchsticks that, for me, symbolized the silhouettes of people davening.

Jewish artists, by choice or by birth, who inspire you?

The list is long! I could talk endlessly about Jewish painters, comedians and musicians I adore. And I also have many favorite Jewish photographers… I am inspired by the honest confrontation of Irving Penn, the natural and personal generosity of Sally Mann and pushed experimental techniques fashioned by Man Ray. I am fascinated by photographers who challenge that which we do not want to confront, illuminating the uncomfortable and unsavory minds of our society, bringing compassionate light onto social issues within our community. They often create necessary controversy that shapes change by highlighting the seemingly unpleasant realities that society ignores. Diane Arbus is on my list for her incredible work in that space. And William Klein for his emotional portraits of humanity and humor in his film “Who Are You Polly Magoo?” I borrowed his photo of two children dressed up for Purim, “Dance in Brooklyn, New York, 1955”: I printed and had it stitched to the Purim outfit I wear in my photographs. I also treasure Noami Wolf’s work, especially her book “The Beauty Myth.” Her teachings continue to shape many of my creative ideas.

Anything that you wish Jews by birth knew about the conversion process? Or about how to make converts feel welcome?

Choosing to convert to Judaism is a beautiful, spiritual decision. Liberal Judaism’s acceptance of converted Jews is beautiful, especially with the conclusion that following the beit din, there is to be no further mention of the fact that you are a convert — you are simply a Jew. I would like Jews by birth to be reminded about how extensive and deep the conversion process is, that it is not a whim and, like any dedication in life, is to be acknowledged with dignity and understanding.

Ultimately it seems to me the most important thing is to treat the person with respect —converting is a big decision and is something to be celebrated. We human beings have so much more in common than we do differences.

“My Name Is Maya” is available to view through October 30 at the Belfast Exposed Gallery, when it will move to the Finchley Progressive Synagogue. You can view more of the exhibit’s photographs in chronological order on Manon’s website and preorder the exhibit book.