There are few things more therapeutic for me than baking bread, challah especially. Kneading the dough is my favorite part, when you get your hands dirty and earthy, covered in flour and eggs and oil. You must follow the recipe exactly, or risk a too-dense, overdone, dry challah bread. Recently, while I was making challah with friends, as I measured out sugar and warm water, I was attempting to use the baking equations to block out the following recipe that was brewing simultaneously in my head:

• Swastikas found on Georgetown University’s campus since September 6: Eight

• “Bias incident report” emails we’ve received: Two

• Responses from the school’s President: One

• Swastikas found on Rosh Hashanah, the second holiest day of the year: Two

• Comments on news articles that speculate that this is a conspiracy by Jews to drum up sympathy for pro-Israel clubs: At least four

• My Jewish professors—three of them—who said something about the incident: Zero

• My professors who appropriated the swastikas in order to vaguely connect it to a concept in class: Two

• My professors who used the swastikas as an insensitive pop quiz question: One

Measure out these ingredients, mix in a pinch of white supremacy and a scoop of radical leftism, bake in a Catholic-yet-kinda-liberal university at high heat, and you end up with a grieving, terrified Jewish community of undergraduates who can’t make anyone understand why they are so hurting.

Early in September, I found myself walking across campus in a daze. I felt like the rug had been ripped out from under me, and that after three years here, I was being told that I was not welcome. Between the evening of September 5 and the morning of September 6, the entire campus received two of the previously mentioned “bias incident report emails,” informing the Georgetown community that three swastikas had been found in undergraduate dorms. One was found scratched in my former freshman dorm, while two others were painted in bright red paint inside of an elevator in an upperclassman residence hall.

I received a cold and clinical “bias incident report” while I sat in my Women’s and Gender Studies class, where I was unable to react while my heart sunk during a lecture on genocide. Soon, a group chat of Jewish students started to flood with chilling pictures of the swastikas. Over the coming weeks, following each subsequent email we received from the university, my peers continued to text me images of the swastikas, all of which came from the same upperclassmen dorm. They were accompanied by explicit language encouraging violence against women, as well as taunting messages such as “catch me.” We felt paralyzed.

The pain was particularly acute for me, as I’m the kind of girl who wears her Judaism on her sleeve: I wear a kippah on Friday nights, jewelry covered in Hebrew from Israel every day of the week, and I tell everyone who asks that I’m planning to become a rabbi. I’m a challah-baking, tefillin-wrapping, loud and proud Jewish girl who never misses Shabbat. I’m making my English honors thesis about Jewish feminism so that I can talk about Judaism even outside of my Jewish Civilization classes. I have made “the Jewish girl” and “the future rabbi” my identity at Georgetown. And these past few weeks, vile individuals have been spitting in the face of that identity.

On the one hand, I know that I’m privileged. Unlike parts of the Jewish community, I’m white, so I’m not discriminated against on the street the way a person of color might be. I’m not an Orthodox Jew, so you might have to look twice at my necklace in order to identify my religion rather than knowing upon first glance. I’m presumably not in any imminent danger, just the target of intimidating graffiti. It’s also important to note that the words advocating for violence against women beneath one swastika affect all women on this campus, not just Jewish women, even if it cuts a little deeper for us. All of this being said, the psychological effects are real. Nonchalant conversations about Nazis in classrooms have since triggered panic attacks for me and others. I found myself crying in the quad on September 7, feeling for the first time in my three years here that this campus might not be my home.

Ultimately, what upsets me the most is not the existence of swastikas—I have unfortunately been conditioned to expect anti-Semitism in many spaces in America—but rather the failure of our community to acknowledge anti-Semitism as a problem that we must confront in our own circles. I’ve been frustrated and exhausted, attempting to be an advocate for myself and my community when it seems like no one “gets” it. Multiple friends have said, “Why are you so upset? What’s the big deal?” I’ve attempted to answer these questions: because the last time this symbol was widespread, my grandfather lost his entire extended family to death camps. Because epigenetics have shown that trauma is passed down through generations, so my Jewish brothers and sisters are actually feeling the same PTSD that their grandparents developed after the Holocaust. Because anti-Semitism is ignored because of hatred of Israel, or because Jews are assumed to be universally white and therefore unable to be oppressed.

The big deal is that this is happening now, at Georgetown, in 2017. And I shouldn’t have to be explaining any of this.

There’s been a lot of emotions to sort through, and a lot to prioritize. Do I focus on my role as a Jewish student leader on campus, and turn within my community to lead prayer and help out those who are hurting more than me? Do I mobilize and educate and actively combat casual anti-Semitism both in liberal spaces where I predominately exist, and in white supremacist spaces that seek to bring back Nazism? Do I ignore the swastikas, not give them attention, and merely take it like so many Jews who don’t want to take up too much space (complicit in their own oppression)? No. I decided instead to bake.

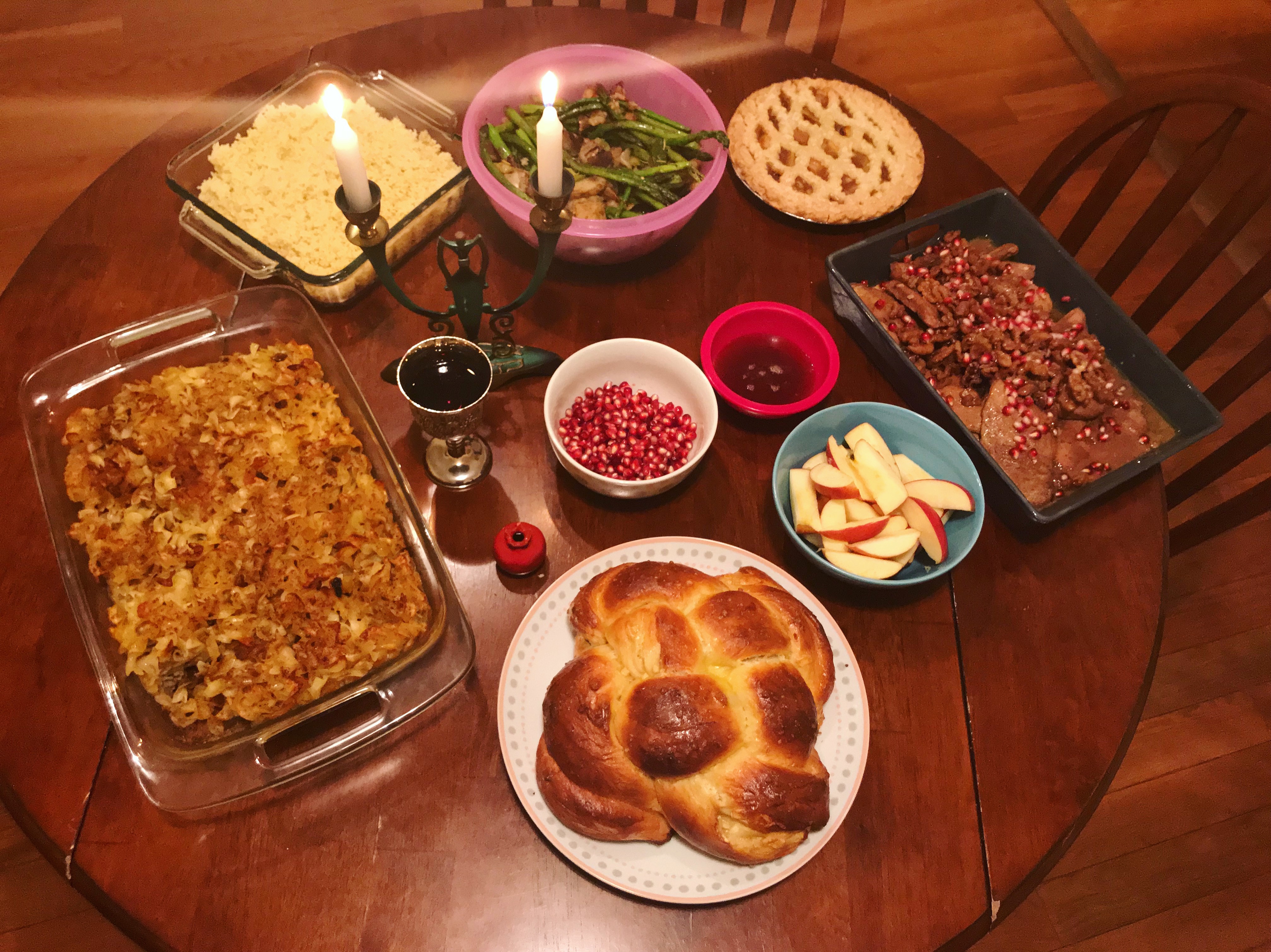

Late one night, a few friends and I gathered at a friend’s house to bake challah. We tripled an already enormous recipe, ending up with three overflowing bowls of dough. We danced in her kitchen to Fiddler on the Roof and klezmer music, celebrating our ancestors who baked challah in the shtetl. In the “old country,” where Jews were confined to shtetls instead of being allowed to participate in mainstream society, our great-great-and-so-on grandmothers resisted this oppression by celebrating our heritage in the kitchen.

While we waited for the dough to rise, we drank wine, chatted, and hugged one another. We didn’t have the answers for what to do on campus. We just knew, as long as we were continuing this tradition that millions of Jewish women have participated in for centuries, we would continue to be OK. That night, we found self-care in punching down a rising mass and slathering hot bread with apple butter. We healed as we braided the six strands of dough together.

And just like the honey that we drizzled into the dough of our apple challah, there has been sweetness folded into the braids of this mess:

• Faith groups represented at Shabbat the week of the first swastikas: Eight

• Non-Jewish friends that reached out to check in on me: Thirteen

• Minds I’ve changed through conversations around anti-Semitism: At least three

• Hugs I’ve shared: Too many to count

I am finally beginning to see the larger Georgetown community slowly wake up to this violence in our midst. There is so much work to be done, on campus and in our country, but I am cautiously hopeful.

In the meantime, I am pausing. As the air gets crisp and I settle into my last fall on this campus, I’m done discussing swastikas. The ball is rolling in the direction of change, and once I’m done with my recharging, I will join in pushing it uphill. But for now, I plan on experimenting with my salt-to-brown-sugar ratio and attempting to master braiding a round challah. As we gather around the Shabbat table in friends’ kitchens and light the candlesticks passed down to me from my great-grandmother, I will find strength in knowing that these acts of self-care are also some of the oldest acts of resistance in Jewish history. And if you want to learn how you can be an ally to me and my people, I will happily sit down with you over a cup of coffee and a thick, buttered slice of warm challah.

A version of this piece originally appeared on Bossier Magazine.

Top image via Flickr/Brendon Ross. Second image courtesy of author.