It was never about the bump on my nose, for me. It was more about the curve, the way an incomplete cleft palate had twisted my nose and lips. And being able to breathe properly — that was kind of a biggie.

“Iraqi?” the ENT asked, almost incidentally. I nodded. “We do a lot of rhinoplasties for Iraqi Jews. Lots from Long Island.”

It was more of a surprise to me that he knew a lot of Iraqi Jews, and that he was one himself, as it turned out. We’re a small diaspora, spread across the world after the 1941 Farhud in Baghdad which scattered Iraqi Jewish families to Sydney, Canada, California — and New York.

“We can get rid of that bump,” he said. “No problem.” He made a note on his clipboard, like it was a box to be checked off. Another Jew, another bump. Of course she wants it gone.

I looked at myself in the mirror he’d given me. “I actually like the bump,” I said. Not everyone wants to get rid of their bumps, I thought. “I mostly want to straighten it. And breathe.”

“Sure, sure,” he said. He mentioned the bump four more times. I touched it each time. I wanted him to understand — that I didn’t want to erase the link I had to my family, the bump I share with my younger sister, with my mom.

I was already having a difficult enough time deciding to get the corrective surgery. I’d lived with the poorly-healed cleft lip and left-leaning nose for 27 years. What would people think if I suddenly got surgery? That I was vain, that I couldn’t stand looking at myself anymore, that I cared what other people thought? I just wanted to breathe well. Adding shame over Jewish noses wasn’t helpful.

The ENT relented a little, and explained that the bump would have to be minimized so my nose could be shifted. Physically, they couldn’t keep it. I asked.

“We’ll leave some of it,” he said. “So it looks natural.”

The surgeons were very happy with the result. I was happy too, after a while, especially with my lip — looking in the mirror was too bizarre for the first few weeks — but the surgeons were over the moon. I got “this is how your face has always wanted to look” and “what an improvement, right?”

The surgeons definitely expected something different from me during our post-op appointments. Maybe they’ve had patients cry with joy at their new features and thank the surgeons endlessly. I was just happy to get the stents out and the cast off. I thought the surgeons, all Jewish, would get that I was stuck on the bump. I guess they’re used to people wanting to rid themself of that marker. To blend in, to be less evidently Jewish. They expected that from me, and I refused to give it to them.

I was more focused on healing, on breathing, on my lip, on convincing myself I hadn’t participated in a betrayal of self. I was, and am, ultimately very glad I opted for the surgery. I’m happy. Honestly, I don’t owe anyone an explanation.

But I miss my Jewish bump.

It’s been a quiet realization. I notice it when I stand next to my sister and look in a mirror, or when I’m at Shabbat dinner with my immediate family and grandma. I do have the coloring of the Wakils, my maternal grandparents’ family: the slightly olive complexion, hazel eyes, and light brown hair. But part of me feels like I’ve kicked myself out of the Sephardic-Mizrahi Jewish club. A guy I was seeing even told me I had a totally goyish nose.

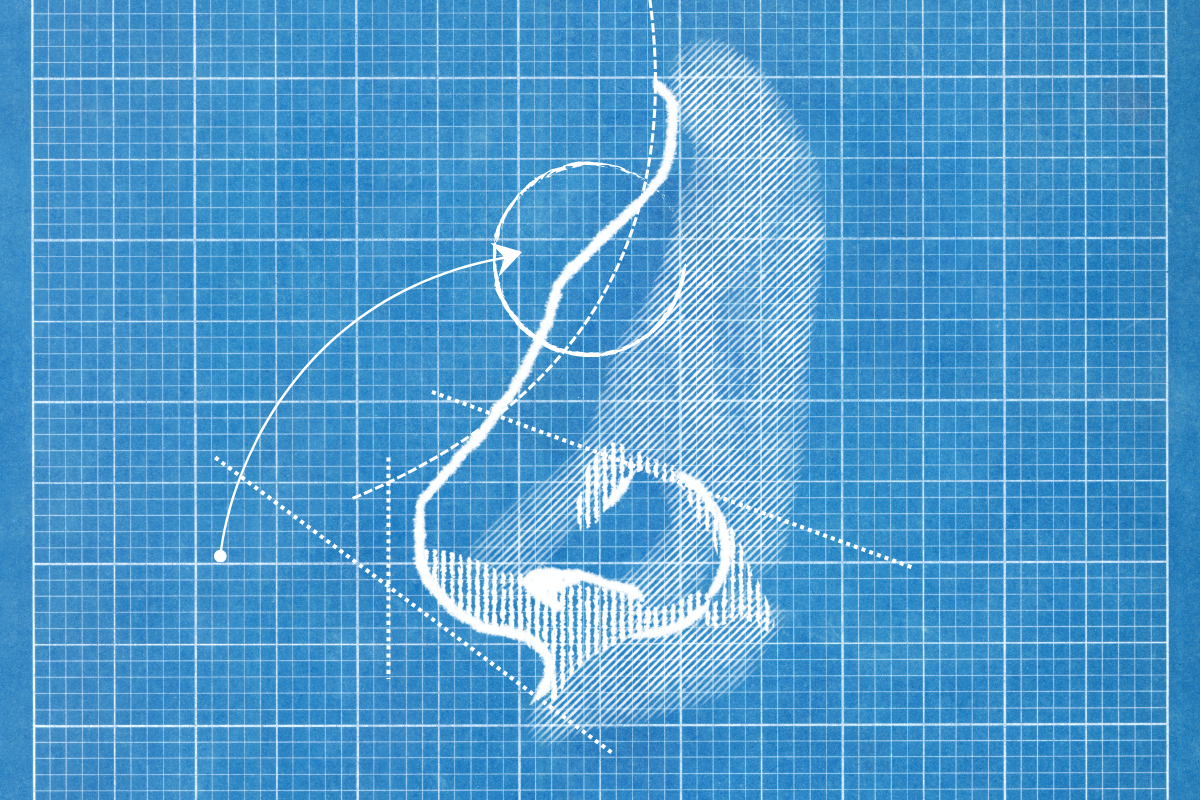

I used to rub the bridge of my nose a lot when I was thinking, feeling my bump, and I’ve started to do it again, now feeling its absence. I think about this little ski slope I have now, which I envied on non-Jewish friends growing up, and where it puts me. Apparently I’m not as Jewish-appearing, but am better at breathing and have a corrected cleft lip. What is it about the bump? Maybe it’s that sometimes being Jewish feels so diasporic, so ineffable, and having a tangible attribute was grounding. Or maybe it’s a reclamation of antisemitic imagery. I think for me it’s about looking like the people I come from.

Even though I miss that little bump, I know that my Judaism isn’t tied to a physical feature. If Jews, especially Iraqi Jews, know one thing, it’s that we wander, that we’re not tied down. My Judaism is the rituals my family practices, the Iraqi stews we have for holidays, my Arabic-speaking great aunts and uncles in Sydney. It’s the special tropes we have for prayers, the Backgammon my grandpa played and the iced tea he made. It’s my badly braided challah, it’s “Broad City,” it’s my belief in freedom for everyone. The little bump I had on my nose doesn’t factor much into it.

“You just look like you,” my mom said recently, and smiled. We were getting ready to light the Shabbat candles. “You know your Auntie Teffaha got her nose done?”

I blinked at her. “You didn’t tell me this sooner?!”

“I forgot,” she said, shrugging, and lit the match.

If my Great Auntie Teffaha, Baghdad born and bred and looking phenomenal at 90, got a rhinoplasty and no one remembers? I’ll be fine. The air I breathe is the same. I just breathe it a little easier.