Growing up, I never felt Jewish “enough.” For starters, Judaism is traditionally considered to be passed down through matrilineal descent, and my mother is Mexican-Catholic. But this presents a problem, too: I’ve never felt Mexican “enough” either.

Yes, my mother and I celebrated Mexican-Catholic traditions, eating tamales on Christmas and Rosca de Reyes on Three King’s Day — inside of which is a small plastic baby, who’s supposed to be Jesus. (Whoever gets Jesus in their slice then has to “host tamales” a month later on Candlemas.)

But my father’s side is 100% Jewish — my 23&Me reads 50% Ashkenazi Jewish exactly — and I grew up celebrating the High Holidays and Hanukkah at my grandma’s, where, aware of her grandchildren’s complex religious identities, she kindly displays both a Christmas tree and menorah in December.

It seems straightforward: I’m “half and half.” But my parents’ divorce when I was young meant split custody, and therefore, split cultures: I was Mexican-Catholic at Mom’s, with whom I’d frequent panaderias downtown, and Jewish at Dad’s, with whom I’d make bagel necklaces at Nate’n’Al’s.

But having never lived full-time at either home, I felt like an impostor in both identities: I was a very pale fake-blonde MexiJew stuck somewhere in the middle, unsure of where I belonged — if anywhere. I just knew I liked carbs. It wasn’t until this year, at 28 years old, that I finally figured out where I belong: in the kitchen.

After my parents’ divorce, I started baking, and from the ages 9 to 11 I was a prolific culinary expert, baking birthday cakes for friends and neighbors and anyone who would take one, going so far as to hold a bake sale/lemonade stand for the first responders of 9/11. I raised $87, and Joan Van Ark was a customer.

My stint as a preteen pro-baker was short-lived, however: Once I started sixth grade I put down the pie tin and picked up a Simple Plan CD, spending my time on AIM and begging my parents to let me pierce various body parts at the mall.

It wasn’t until 2020 — 17 years post-adolescent culinary phase — that my passion for pastries returned with a vengeance. Tragedy seems to bring the bug out of me — not that my parents’ divorce and a pandemic are on equal footing, but to the naive 9-year-old mind, the obliteration of family as I knew did certainly seem like the worst thing I’d ever experience. So it’s reasonable that, newly unemployed and stuck at home amid a pandemic, I’d rekindle my rocky relationship with the kitchen. (Post-preteen but pre-COVID, the only food I could cook was eggs.)

What started with bread (like everyone else) quickly evolved into elaborate tarts, and within a week, I’d run out of places to store them. Stubborn to the obvious solution — as in, simply stop baking, or at least take a break — I offered neighbors and healthcare workers free baked goods to keep my new-but-old-found hobby up without crowding the fridge (or my stomach). Within a month, my Instagram had become one of those accounts: tart after cake after pie after pie…

To my followers, I was tart master; my Instagram grid had never looked more aesthetic. But in reality, I was using desserts to distract myself: Living in New York, the pandemic epicenter, while my family was across the country in LA, I had (and still have) no idea when I would see them next — and that’s scary.

Then I realized that baking was a way for me to connect with them.

It started with a flan — a failure of a flan. The caramel was burnt and the custard, an evil omelette. I took two bites and threw it away, crying. To me, this was the irrational proof that I was, in fact, not a real Mexican.

“I made a horrific flan,” I wailed at Mom via FaceTime. She wasn’t concerned, though. “Flans are tricky. Don’t make flan. Even good Jello is hard to make.”

That was enough reassurance for me — whether it’s true or not. I thought back to Jello shots I’d made with ease. Alas. “Don’t make flan.” Noted.

Post-FlanGate, I FaceTimed my mom each time I embarked on new Mexican food. Together we recreated the tres leches cake she’d made for me growing up — well, a gluten-free version — as well as chilaquiles verdes and gluten-free churros. (Did I burn my hand in boiling oil in front of my mom on FaceTime? Yes. Was it worth it? Also yes.)

Excited and proud to finally “feel” Mexican, I posted pictures of my Mexican meals to Facebook and Instagram. “It must be in your blood,” impressed relatives replied, many of whom were from my father’s side. Then, I realized: I was ignoring half of my identity.

It was time to make some Jewish food.

I already had the essential hand-me-down cookbook in the house, which I’d unintentionally resurfaced while sorting through spices. The Art of Jewish Cooking, from 1958, features adorable illustrations — the sour cream on the front is the cutest thing I’ve ever seen. It was passed down not from any of my family members, but my husband’s grandma — my husband who, unlike me, “genuinely” grew up Jewish. His family kept kosher, held weekly Shabbats, and he was, of course, bar mitzvahed. In present day, however, he no longer practices, so he’s a bit like me, living in an in-between Jewish land (though he still very much identifies as Jewish).

And so I began my journey to Judaism via its cuisine, dragging my husband down memory lane right along with me.

Prior to my revelation, the only foods that came to mind when I thought of Judaism were bagels and latkes — which I love. But that felt like cheating, plus, post-churro-burn, I was skeptical of deep-frying or boiling anytime soon.

So I opted for another, sweeter classic: chocolate babka. (Cue Seinfeld.)

I studied for that babka harder than I studied for the SATs. Or GREs. I think I was better prepared for babka baking than I’d ever been for anything else in my life — it felt like a test, the test: my Jewish test. And with FlanGate still jiggling heavily on my mind, I simply couldn’t fail this one, too.

Apparently the preparation paid off, because when the day finally came to make the babka, it was a piece of… well… babka. And it was, up until that point, without a doubt the best thing I had ever made (a sentiment echoed by my husband, who regularly requests I make it again). The bulbous babka was eaten entirely in just a few days.

Sugar-high off my babka boom, I confidently returned to the kitchen seeking my next challenge: challah.

I made my first challah on a Friday afternoon, in preparation for Shabbat — which, despite having been together for nearly six years, my husband and I had never actually experienced together.

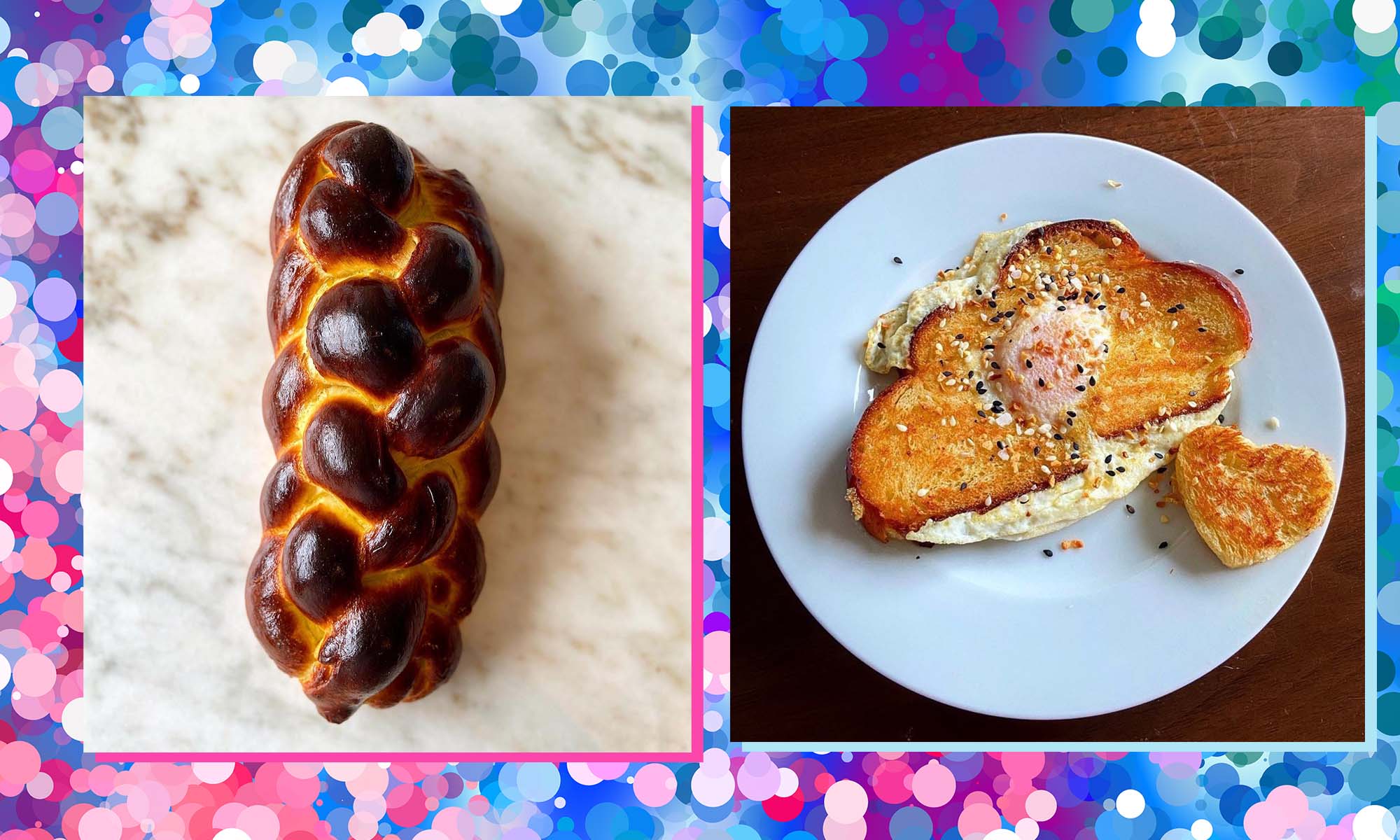

Quite like the babka, the challah was devoured in an instant, though I saved just enough to make a challah “Egg in the Nest,” my no-longer-with-us-Nana’s specialty, the next morning, thrilled to finally combine my cultures — with the one food I actually could cook all along.

That night, I started my first kitchen fire making latkes.

It’s been exactly three months since I started baking. And I’ve learned a lot: For one, you can teach an old dog new tricks, even in the kitchen, and even when it comes to their heritage and religion. It turns out there’s no “right” way to be Mexican or Jewish — let alone both — and a life spent chasing that is one spent wasted. I let years go by during which I was ashamed of who I was, thinking I wasn’t properly embodying what my ancestors would’ve wanted me to be.

But once I started baking, I realized they would’ve just wanted me to be me, not some cartoon idyllic stereotype. That’s not real. But all the foods I’m able to bake and reconnect with family over are. I even mastered bagels and rugelach. If that’s not real I don’t know what is.

Once this occurred to me, I faced my fear of my “fake” Judaism and entered a Jewish baking contest, for which you submitted photos of food accompanied by a caption of why Jewish food is meaningful to you. My caption was essentially the beginning of this essay: That growing up, I never felt Jewish enough, but since I started baking, that changed. And guess what? I not only won the contest, but it turns out a lot of other people felt the exact same way. We all felt alone, together, and that was the best prize I could’ve ever asked for.

Today, Jewish and Mexican treats are staples in my home, so much so they’ve evolved into one: On Fridays I make what I call a “self-portrait,” a challo (challah/churro), a sweet braided challah spiced with churro seasoning.

Quite like the challo, identity is complicated and intertwined. For me, each strand represents a different part of who I am — centuries of traditions passed down from Eastern Europe, Spain, and Mexico, all of whom have now found a home, braided as one in my Mexican-Jewish Brooklyn kitchen.

Get Danielle’s “challo” recipe over at our partner site, The Nosher.

All images courtesy author. Design by Emily Burack, background via Getty Images.