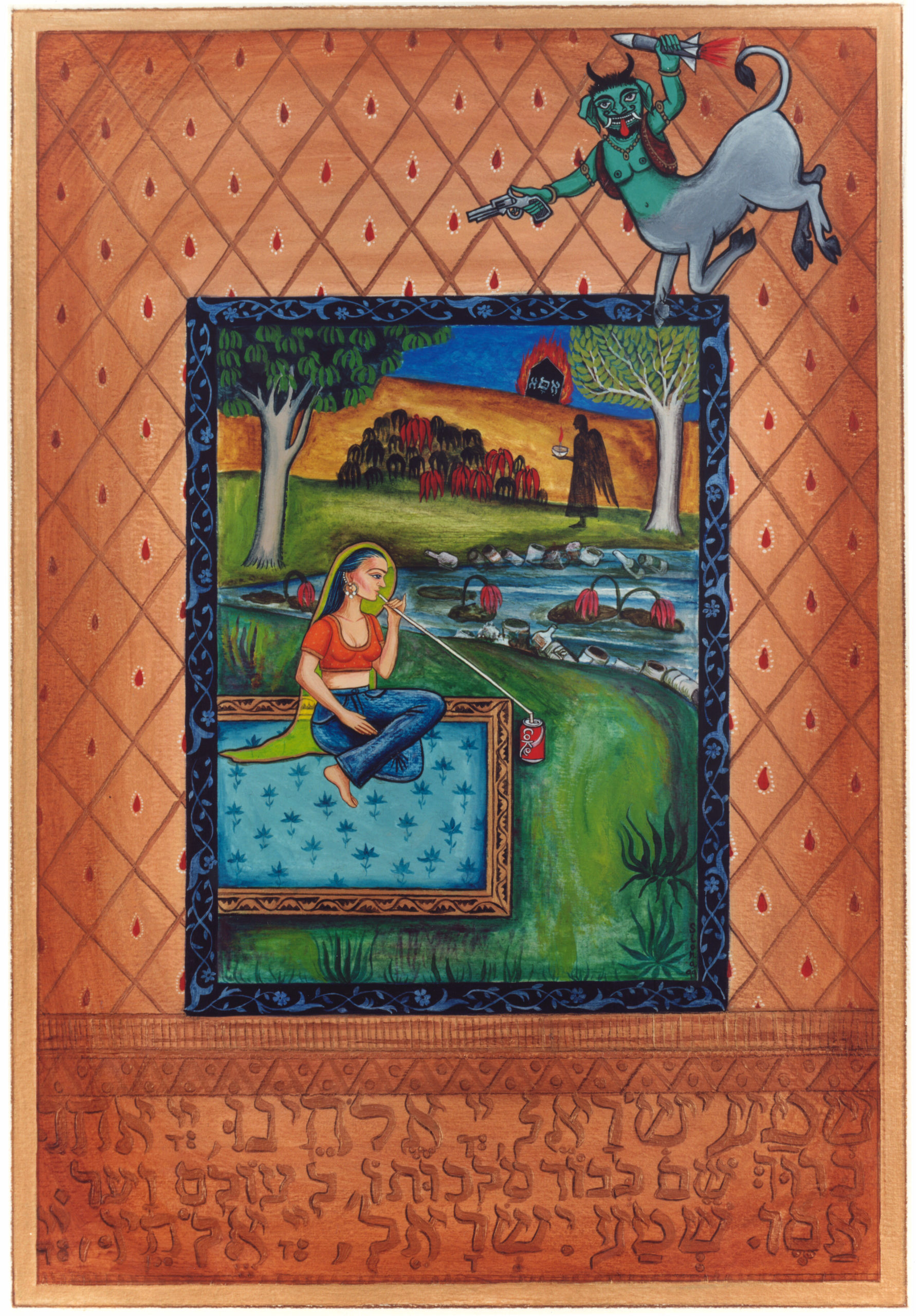

In the 28th painting in Siona Benjamin’s “Finding Home” series, a young woman sits on a rug in a world resembling that of Indian and Persian miniatures: a flowing river, large flowers and a dark winged figure lurking in the background. At first glance, the woman appears to wear a sari. But on closer inspection, that’s only half of the truth: She has paired the traditional Indian garment with blue jeans. From her mouth, a straw extends into a red can of Coca-Cola.

These kinds of hybrids and anachronisms permeate Siona’s work. She grew up in Mumbai’s Jewish community, and her paintings reflect “being brought up Jewish in a predominantly Muslim and Hindu India.” In the 2015 documentary “Blue Like Me,” which follows Siona as she returns to visit and document the Indian Jewish community where she was raised, she calls out the spiritual challenge of understanding Judaism as a child: “How do you survive in an icon-filled country being told that your Jewish God is abstract and exists in the little flame [of the Shabbat lamp]?”

Now based in Montclair, New Jersey, she makes art that, in her own words, “combines the imagery of her past with the role she plays in America today, inspired by both Indian miniature paintings and Sephardic icons.” As she explains, “Growing up in a predominantly Hindu and Muslim society, being educated in Catholic and Zoroastrian schools, being raised Jewish in India, and now living in America, I have always had to reflect upon the cultural boundary zones in which I have lived.”

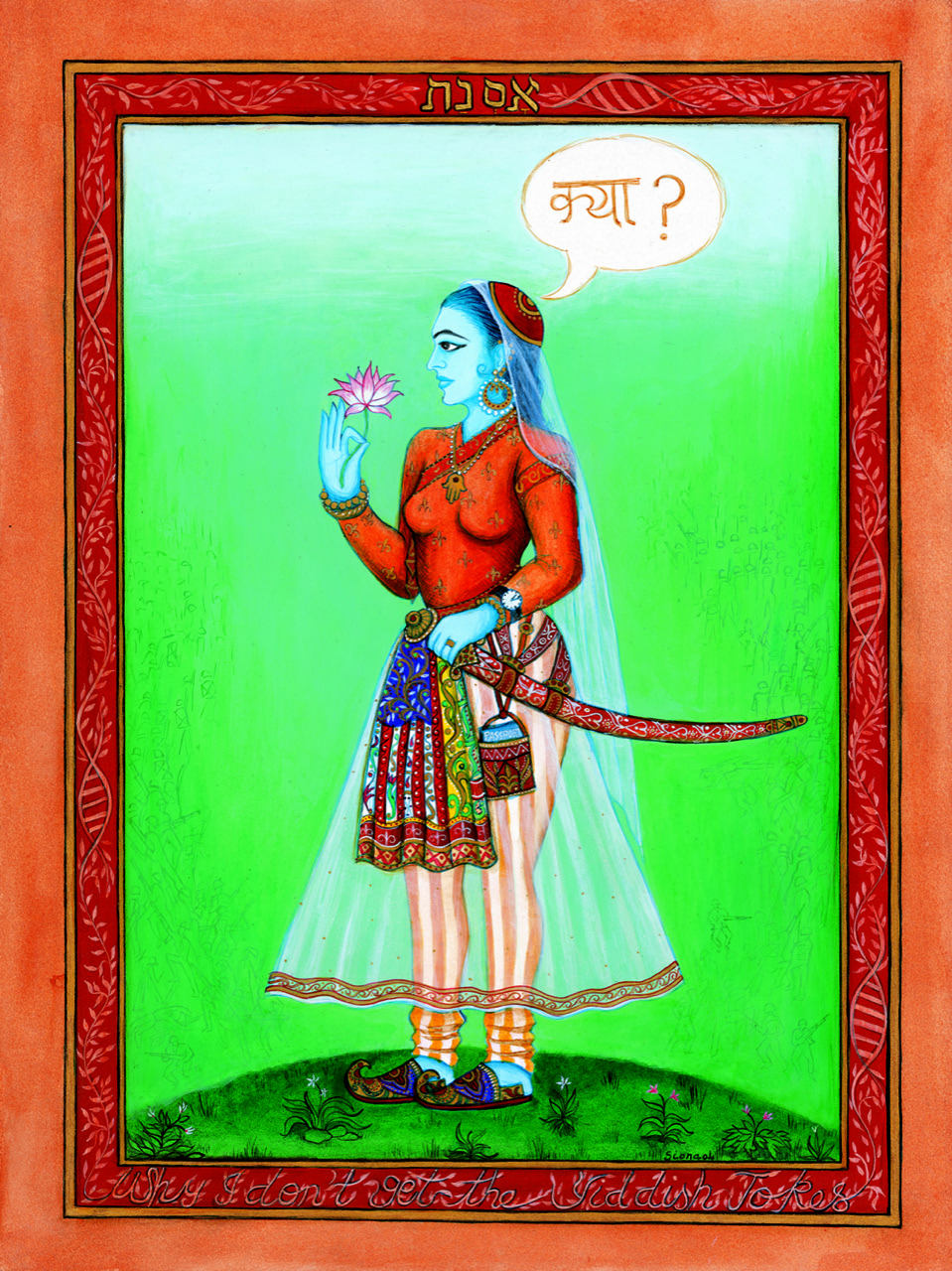

That first-hand knowledge of being othered, and the desire to express the universal, led her to create a blue-skinned character who appears in many different forms in her paintings. “Very often I look down at my skin and it feels as if it has turned blue. It tends to do that when I face certain situations, such as when people stereotype or categorize others who are unlike themselves,” she has said of the inspiration behind her color choice. “The blueness and the blue skin has become a symbol of being the other. The lightness of the blue… it could be the blue sky, it could be the ocean, and that stretches all over the world. I could belong everywhere and nowhere at the same time.”

Siona draws freely from pop culture and comic books as well as from biblical and classical forms. That undercutting of traditional styles means that her work brims with unexpected humor. Sometimes, her blue figures wear baseball caps. Other times, they’re strange creatures, curiosities: a woman who twists into the boughs of a tree, or a long-necked horse with a woman’s head. Jewish imagery is present in almost every piece of work, mashed up with Hindu deities: In one painting, the arms of the god Shiva become the branches of a menorah.

She expresses her frustrations in her art, too. She turns microaggressions into images: When someone at a school she visited asked her if she’d ridden there on a camel, she painted a figure doing just that to deal with the absurdity of it. Hidden around the border of another image, in script, are the words “I don’t get the Yiddish jokes.”

Siona recently talked to me over Zoom about her upcoming projects, how the perception of Jews of Color has changed over time, and overcoming the narrative of Western art’s superiority.

This conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

I see a beautiful in-progress painting behind you. Can you tell me a little more about it?

Absolutely. I’m inspired by the sleeping Buddhists — in Thailand and in Sri Lanka and even some in India. So I’m doing this eight-foot-long sleeping giant Lilith. I do my own projects in between my commissions because I have to earn a living and I have to pay my bills. I just finished another piece, a retablo-style triptych called “Amistad.”

As far as commissions, I’m making a ketubah for a wonderful young couple, I’m making tiles for a swimming pool, and then the third commission is the most intense: I’m making a scroll for Ohev Shalom synagogue in Pennsylvania. I did a whole commission for them last year where I did parochet, the Torah ark curtain, and amud, the table cover. They hired me to create an eight-foot-long scroll, which tells the story of the lost scrolls of Czechoslovakia during Nazi times.

Oh, wow, that sounds incredible.

I’m doing a lot of research on difficult subject matter. These scrolls were hidden in the synagogues, and then the Nazis were looting the Jewish objects — then they were taken to a synagogue and to a church in Prague, and then to a synagogue in Czechoslovakia, where they were stored. In the town where they were stored, there was a famous rabbi, and he died early, so his wife wrote the first prayer book for women by a woman. Her name is Fanny Neuda, and she’s pretty incredible. So she’s in the story, too.

So you’re making a scroll telling the story of the scrolls.

Exactly.

Do you have a consistent process, or does it vary from piece to piece?

A lot of my work is research based. I like to get into the meat, or the substance — I don’t eat meat, so meat is not the right word. I like storytelling, I like recycling stories and mythologies to give them new life. I think mythologies become static if they are just retold and told again. But, for instance, midrash is about reinterpretations and putting your interpretations in there, and that breeds new rejuvenated life into it.

I’m doing this project on the scroll, and I’m getting more and more involved. I was reading about who the parents of Hitler were, and I had never bothered to find out before, but I dug deeper, and I found out that his father married this niece of his, and it was very incestuous, which gives me a greater understanding of how this man was created and how his upbringing was. So in both my personal projects and my commissions, I like to know as much detail as possible.

You make art that is for display in the traditional museum or gallery sense, and then you also make art that’s for use in daily life — on blankets, pillows, mats, shawls. I know you’ve designed for theater, too. Do you feel like art is different in those forms? Or does it all come from the same place?

Two things. One, I am an artist that has taught myself to think more practically so that I can make a living. I’m trying not to stay with that stale old story about poor artists who can’t make a living. I’m trying to break that stereotype and also be more innovative.

But on the other hand, I also want art to be more affordable to a lot of people. So even younger people who really like my art but can’t afford a $7,000 painting can buy a print of it, or a shawl with the image on it, or a yoga mat. I don’t feel like art should be elitist and just belong in museums, “do not touch.” This makes it more touchable, more wearable, more … you know, it embraces you, by wearing a shawl. You walk on it when you have a yoga mat. It just makes it accessible in so many different ways.

I want to circle back around to Lilith, behind you — she’s in a lot of your work. I want to hear more about how you found her: What drew you to her initially, and how has your relationship with her changed over time? Are there more stories, from Jewish mythology and other mythologies, that you draw from?

Many years ago, I was not very familiar with midrash. In the early 2000s, when I moved here, I presented my work at a synagogue and the rabbi there said that it was very conducive to studying midrash. And I said, no, I don’t want to study religiousness in my work. He said, it’s nothing to do with religion, it’s about recycling mythology.

So when I started studying, I got introduced to these women in the Torah, from Sarah to Rebecca to Miriam — I love Miriam also. But most of all, I like Lilith and the other women in the Torah that have been left out, like Vashti or Tamar or Tzipporah, who’s supposed to be this dark-skinned, non-Jewish woman who marries Moses. And then, of course, Lilith, who is completely left out of the canon, because it’s just Adam and Eve, and Lilith is very rarely discussed, and in a harsh way when she is. But this is part of the mythology, that there was Adam and Lilith before there was Adam and Eve.

That’s how I got introduced to women characters that are on the periphery, and started identifying with them as a Jewish woman of color. People often ask me, “How come there are Jews in India?” when there have been Jews in India and that part of the world for 2000 years. That’s fine if it’s part of an education, but having to explain and re-explain that, I kind of became the “other” woman, the woman that is on the periphery and belonging everywhere and nowhere. That feeling is conveyed with these characters that are not in the mainstream. All of them are interesting, Sarah and Rebecca and Rachel and all of the matriarchs who are in the mainstream. But the ones that are on the outside — and Miriam, who is in the mainstream but who does things that make her rebellious and asks difficult questions — intrigued me.

As you’ve begun to explore midrash, what role does Judaism play in your daily life?

I was raised very Jewish, by a very Jewish family in India, and my grandmother lived across from the synagogue. I’m doing a book called “Growing Up Jewish in India,” which should be published shortly, which talks about this.

Then I came here, my daughter’s bat mitzvahed, I belong to a synagogue. I sometimes forget to even light the Shabbat lamp on Fridays. I think my work has become my religion. And I feel great satisfaction in it.

Before, [my Judaism] was the ritual of being with family, but since I don’t have that much family here, mostly they are in Israel, the work has become the religious aspect of what my spirituality is. And I feel full through my work, enough that I don’t need to do the actual ritual anymore. If I miss Shabbat, I know I’ve observed Shabbat by doing something else which is more meaningful.

But I still enjoy going to synagogues and being with family when I can, when I’m in Israel. It’s nostalgic, and it’s wonderful — the ceremonies that Indian Jews have, like the malida ceremony, which is a prayer to the prophet Elijah. And that is very uniquely Indian Jewish. All those kind of nostalgic memories of smells and tastes are there but I can’t practice in a group because I don’t have any Indian Jews around me. So what do I do? You know, I find that through my work.

You draw from so many different influences, and I’m especially curious about your relationship to Indian references that are less known in the West. Are there particular comic books and characters from your childhood that you have in your mind as you work?

If you look at Amar Chitra Katha comic books, these are Indian comic books that came out in English. I mostly spoke English because of the British influence in India, I had an English education all my life. I think those were very influential to me. These Amar Chitra Katha comics were our stories: about Hindu mythology, Buddhist mythology, some Muslim stories. Everything from the story of the Ramayana to Sita and Rama to Draupadi — all these fantastic stories of flying chariots, and horses and kings and the golden age of India when supposedly there were all these beautiful princesses and gods who had blue skin and purple skin.

This mythological world was always around me growing up Jewish in India, but my Jewish family and traditions told me that you can respect them, but you can’t bow down to them. I observed them from a distance, and was fascinated by them.

Is there ever any conflict in your mind, or tension, as you combine techniques from cultures that have been in conflict? Colonizing influences and indigenous ones?

I think so many great artists are influenced from everywhere — everybody from Picasso being influenced by Africa, to Van Gogh being influenced by Japanese prints. Appropriation is a very big word right now. But I think if you borrow responsibly, it can be OK. For instance, someone could ask me: You’re a Jewish artist, you’re an Indian artist, why are you using Islamic miniature influence? But I lived in India; I was surrounded by Muslims. I own a part of it — I didn’t just look at a book and start copying Indian miniature, I actually studied Indian miniature painting. There’s a Western female artist whom I know who goes to India every year and is so influenced by India. Is she appropriating? She’s really embedded herself in it.

But I was asked in school “why are you doing Indian miniature, it’s tourist art. It’s not real art. It’s not high art.” Even my undergraduate professors in India were copying Impressionist-style paintings, because Western art was always high art. And so that inferiority complex was there but nevertheless I persisted on my own path. And things are changing now: Chinese artists are pulling from their own influences, for instance. It’s become more accepted. But before that, many Eastern artists were aping the West.

Art cannot be made in a void. It has to have influences. The challenge is how you change it and make it your own. If you don’t challenge it enough for it to become your own, then I think it becomes copied or appropriated.

You went back to visit your Jewish Indian community and to document some of the people there. How is the community doing today? Do you have a connection there still?

Yes, I have connections with some people. I have a member of that community who is like my brother. A few years ago, I brought 25 or 30 people from a synagogue in St. Louis that I did the floor for. And he is a Jewish historian, and he conducts tours of Jewish India. And it’s fascinating. So he’s asked me to lead a tour of artistic Jewish India, and he’ll be there, too. We were planning it for next January and the January after that, but with the pandemic, I don’t know whether it’s going to happen.

With the coronavirus crisis, I found out that 15 Indian Jews have died so far out of the 4500 Jewish people left in India. It’s a very small community left there and most are in Israel now… over 100,000 Indian Jews now live in Israel.

For a long time, you’ve been visible as an artist who is Jewish in a way that some people find unexpected. Have you noticed any shift in recent years in the perception or awareness of Jews of Color? Are things changing?

Yes, there was much less of an awareness of Jews of Color. That got me into making my characters blue-skinned. I felt I kind of turned blue because my own Jewish people, no matter where they come from, kept asking me, “How come there are Jews in India, how is it possible?” — not like, “Oh, tell me your story,” or, “Oh, I’m intrigued, I want to know more” — but “how is that possible?” As if there’s some wall that would restrict us. I’ve been asked repeatedly, and I have to tell them that that’s where we were, in Mesopotamia. That’s where we came from. So what are they talking about — authenticity? Don’t question my authenticity, and I won’t question yours.

I think now there’s a much greater understanding, appreciation and celebration of diversity — because of certain racial tensions in our country, unfortunately. In Israel, there used to be a much lesser understanding of, and almost racist attitude towards, Jews of Color. There are Ethiopian Jews and Moroccan Jews and Indian Jews, but they were made to believe that they’re supposed to be more Ashkenazi, or more Western, and their beliefs were discounted and their mythologies were supposedly not as authentic as the Western Jew’s. But I think now things are changing a lot, in Israel and otherwise. People want to know the stories but they ask in an inquisitive way, and not in a demeaning way. Still, there are situations where people have asked me very, very weird questions. Basic ones: Are there cars in India? Did you learn to speak English here?

I’m a Jew from India. My grandmother was a Jew born in Quetta, Pakistan. There were Jews there. There were Jews in Karachi. There was a synagogue there for centuries. There’s still a Jewish cemetery there. And people are like, how is it possible for Jews to be in Pakistan and Afghanistan?

Centuries ago, people lived amicably together. Muslims were saving Jews from the Inquisition. So yeah, people coming from all over the place and looking different is something that should be celebrated instead of questioned in a suspicious way.