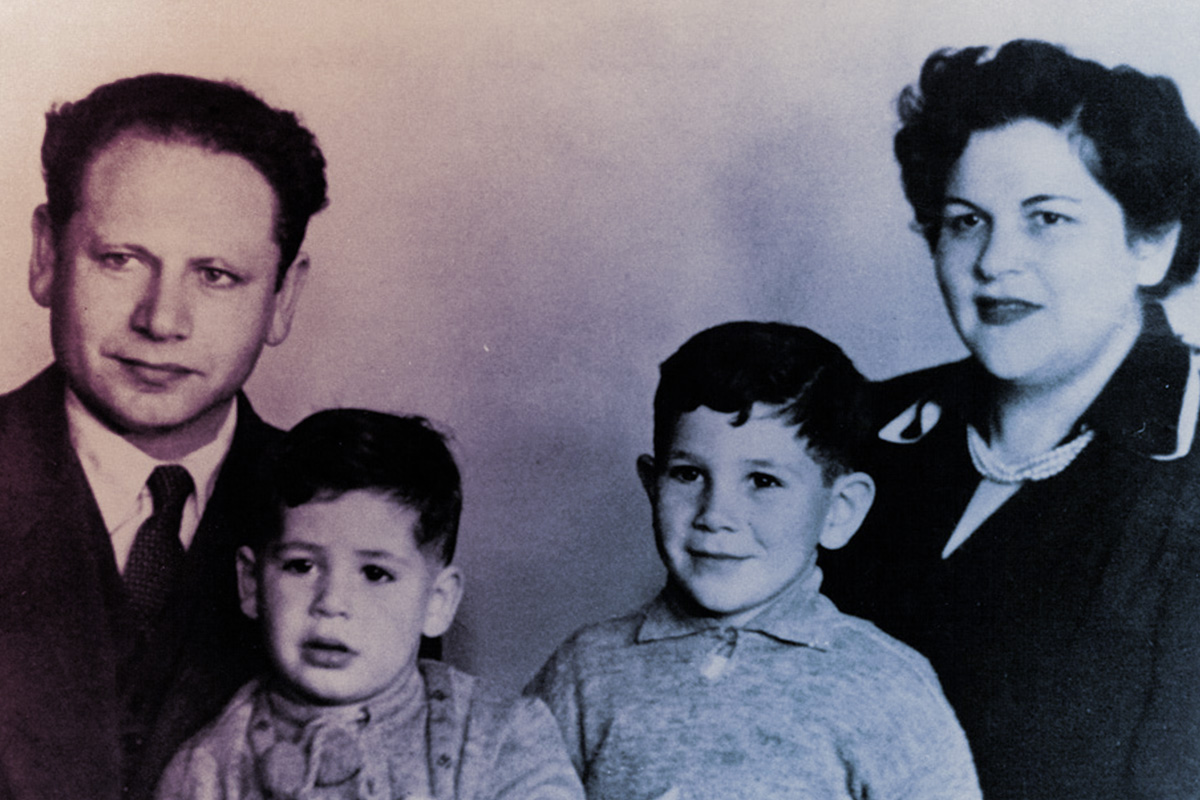

Joshua Cohen’s latest novel, “The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family” imagines one disastrous night in the winter of 1959/1960 when Benzion Netanyahu, the historian and father of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, interviews for a teaching position at a fictional college in upstate New York. Selected to be Benzion’s guide to campus, and put on the hiring committee, is the one Jewish man in the history department: Ruben Blum, our narrator. What results is a moving, funny story of Jewish identity, assimilation, history and more. It’s a mix of fiction and nonfiction — the elder Netanyahu was, indeed, a professor of history, and spent time in America. In an author’s note at the end (minor spoiler alert!), Cohen writes the book was inspired by Professor Harold Bloom’s story of Netanyahu interviewing at Cornell.

“I like the words ‘minor’ and ‘negligible,'” Cohen tells Alma. “Whenever it says minor and negligible, I say, ‘well, that’s where the truth is.'”

In May, before Israel would once again erupt in conflict and Benjamin Netanyahu would be replaced by his former chief of staff, we chatted about all things Benzion Netanyahu, Jewish history, and how he ultimately hopes his book is funny.

Minor spoilers ahead for “The Netanyahus.” This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Let’s start at the end. In the “Credits & Extra Credit” chapter, you note that this story of Benzion Netanyahu was one of the last stories Harold Bloom ever told you. What struck you most about the story when you first heard it?

When Harold was asked about the top 10 stories of his life, this was not anywhere near the top. Harold — it’s hard to talk about him in the past tense, because he was such an alive figure. Just reading a sentence of his brings him back. Beyond his sort of famous — or infamous — reputation as a scholar, a critic, a writer, a hermetic gnostic, but also as a popularizer, he was also a wonderful storyteller. This aspect of his career was never really put on onto the page. He never wrote a memoir. He never really told stories on the page in the same way that he told them in person. And he had so many stories!

This one was a very, very minor one that he sort of offered in passing, noting some overlap between himself and Benzion Netanyahu. And I asked him to tell me the story, and then I asked him to tell me it again, and tell me it again. Every time he told it, certain details changed, certain things get moved around, and so it felt ripe for fictionalization. This encounter with history was among the most interesting to me, from a political standpoint, which is not necessarily the way that I think Harold thought about [it]. I don’t think you think about personal relationships, or these personal encounters you have, in a political way. I don’t think he had that distance.

Where do you find the line between fact and fiction? How do you blur the two?

Slowly. I had permission to do what I would, but at the same time, part of that permission from certain parties has to do with putting certain limits in places. Truthfully, the history that I was interested in was the sort of pre-history of the Netanyahu family and the history of of Benzion Netanyahu in Palestine, and then in New York and suburban Philadelphia. How did he get here? Why? Why was the family here for so long? What was his career like at Hebrew University? What was that atmosphere? What was the Jabotinsky circle like?

Certainly, there are a number of histories of these circles. But the truth is that Benzion Netanyahu, despite his middle son’s sort of beatification or canonization, was a fairly minor figure who doesn’t actually figure into many of the histories of the period. So, it was about tracking down some older professors who still had some memories. And a lot of this was an academic game of telephone.

The subheading of your book is “An Account of A Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family.” Do you really believe this is a minor and negligible episode, or do you think this story is actually key to understanding Benjamin Netanyahu as we know him today?

I don’t [think] the book’s only intention is to talk about is to talk about Netanyahu today. I mean, I don’t even know what Netanyahu is today. It’s that paradox: The more that’s written about someone, the less you can get a handle on who they are.

I wanted to write something about contemporary politics, and I wanted to write something about the identity politics and the campus politics that are around us. There’s a lot in Benzion Netanyahu that’s really about the tribalism that happens when these large ethnic or racial collectives collapse — these empires collapse, and they collapse into tribalism. Benzion saw it in Poland, where he was from, after the First World War. And the lesson you take from that is: When you can’t have legitimacy as a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian empire, or a free Poland, you’re inexorably attracted to a group that will define you, identify you, take you in, and provide for you. This idea of who are your people? Who is your tribe? Who are your alliances? These questions have really come back to us in a strange American context. I wanted to look at these roots of these ethnic politics and racial politics.

I also wanted to explore what it meant to be left out of history, in a strange way. With Benzion Netanyahu, there was this seething resentment of a person who had “deserved more” and thought that he should have had a role in the early state and he was a man born to lead. But, during the most important decade in modern Jewish history, when the state of Israel is being founded and Jews are being slaughtered in Europe, he’s in America. There is a certain kind of return of the repressed when the father who is kept out of history raises the son who must return and destroy. A lot of these were the questions that were stirred up under Trump, and the idea of writing about these things directly was somewhere between boring and too difficult. So I felt like this “minor negligible event” had all of these possibilities.

Ruben Blum says he is a historian who happens to be Jewish, not a Jewish historian. Does the distinction matter?

Well, it depends! If you’re looking for someone who knows about the history of Jews… I think that’s one of the questions of the book. Does it matter?

In a way, making him a professor of taxation was getting him farther away from Harold, you know, and asserting that there is this difference. But really, it was about trying to draw some comparisons between the past and taxation. The idea that from a creative sense, the past is a tax on the present. And even though you didn’t work to incur these debts, you still are constantly paying them off, but there’s not a single decision you can make now that doesn’t have this historic tax on it. And so, whether one is a historian of the Jews, or a Jewish historian: It’s really a question of what is the tax?

Do you think of yourself as a writer who happens to be Jewish, or a Jewish writer? Does it matter there either?

I don’t know. I mean, I’m a writer in the English language. To my mind, the idea that either of those distinctions mean anything is sort of crazy to me. At this late date in history, and it’s always getting later, I don’t even know what the word writer means anymore.

What do you mean by that?

I mean that, when I use it, and I recognize my own biases in it, I usually mean novelist, and I definitely know how out of step with the world that is.

Why are you drawn to telling Jewish stories?

I think I’m mostly attracted to not selling many copies! [Laughs] Yeah, I don’t know. I think I can only write things that I can feel through. Writing is so difficult, it’s such a ridiculous thing to do, that the idea of committing myself to making something to which I didn’t have deep personal concern — a private concern separate from the from the product of the book — is crazy to me.

If the Netanyahus did read your novel, what do you imagine their reaction would be, or what do you hope their reaction would be?

I would only hope they’d be foolish enough to sue me! Look, I don’t want to be mean about this. Talking about someone’s parents, about someone’s father, is difficult. In a way, you surrender some of that some of the privacy when you become Prime Minister, and certainly when you become the type of Prime Minister he is.

I would hope that I presented a lot of Benzion Netanyahu’s ideas accurately. I think his character is something that his two living sons would be critical of. I wouldn’t know about Iddo, but Bibi — his self-presentation is so manipulative. He fluently comes in and out of this American style. Yet, he’s at such pains when he’s home to bury the American side of him. And then when he’s here, he code switches in this very virtuosic way. It’s fair to ask: What is American about this family? What is, and what continues to be, American in his confusion of ideologies? What is this ethno-nationalism that was incubated in an American space? Because I think it could only really have grown like that in America.

The politicization of Jewish suffering is something that concerns Benzion throughout, and his work is about “turning traumas into propaganda.” His son is picking up on that idea, it seems. How do you view the work he was doing in the 50s and 60s through a modern lens?

Absolutely. And frankly, a large discussion in American culture in general is: How do you write unlikeable characters? Should we give space to unlikeable characters? To me, the answer is we should always be writing unlikable characters, and we should actually give as much space to them as we need, because this is the only way that we understand them as humans. It demystifies. While I saw a lot of Bibi in Benzion Netanyahu, I also see a lot of myself, of novelists in general, in him. Here was a man who lived in relative comfort in America, for whom every moment was an emergency. Every morning when he woke up, the world was burning. A man who — in a free society that wasn’t try to kill him — had the freedom to live in a bubble of his own panic, and had to create the panic that his society was not providing for him. To me, that was a pretty good illustration of what it feels like to be an American novelist.

A bubble of panic! My last question: What conversations do you hope happen around “the Netanyahus”?

I just hope it’s funny! We’re talking this whole time and it seems like I wrote like a treatise on something. I hope there’s some jokes. There are a lot of questions about history, who gets to write history, how can history be used, and revisionism that are really salient in an American context. At the same time, I hate the element of literature that constantly seems like I’m asking people eat their fucking vegetables. I will say that people have this idea that “I’m reading a book to better myself, and then I’m going to get stoned and eat ice cream from the container and I’m going to watch ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’ or ‘Seinfeld.'” And that’s Jewish culture, too. I guess what I would like people to take away is that books are as funny, if not funnier, than a Larry David creation. And, on top of that, there’s some history. The self improvement narrative of literature is something I’m really allergic to. I hope what people take away from it is that horrible, forbidden, goyische thing called pleasure.