I first heard of The Klezbians when I was transcribing queer oral histories for JQT Vancouver’s project “The BC Jewish Queer and Trans Oral History Project.” Founder Carmel Tanaka started the project to ensure that the stories and lived experiences of elders in the Jewish queer and trans community in British Columbia, Canada would be preserved — to show future generations the struggle, resilience and sheer chutzpah of those who paved the path for LGBTQ2SIA+ Jews to be loud and proud today. The Klezbians are the epitome of Jewish queer pride.

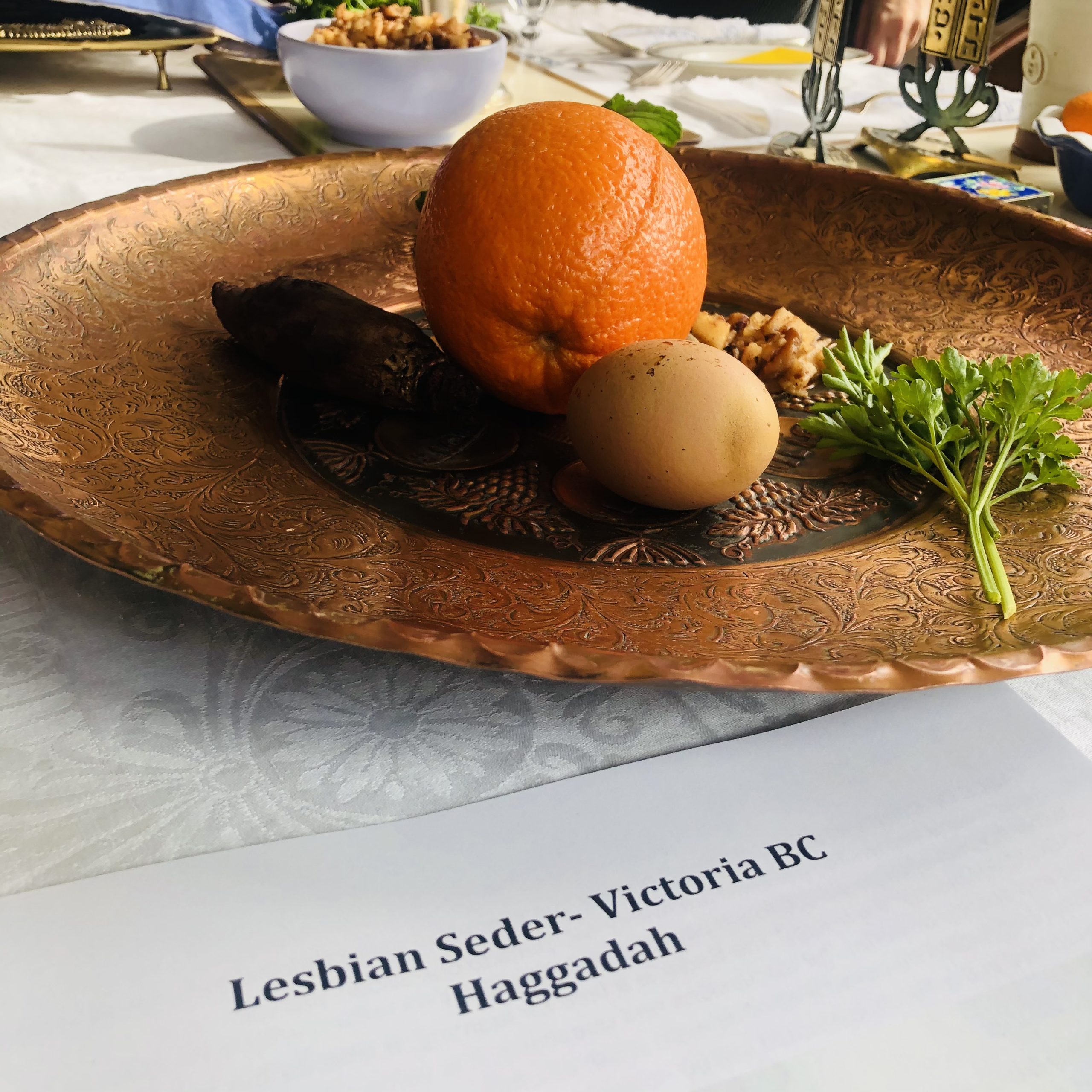

The origin story of The Klezbians varies according to who is telling the story. For Debby, The Klezbians started at an annual lesbian feminist seder she and her partner Donna attended. When Donna turned 40, she picked up the accordion, and at one seder, she started playing while the group sang “Dayenu.” The other ladies asked if they could have instruments so that they could also play. Susan, a little drunk, started to play her accordion. Lauren played the flute.

Donna died of ALS on December, 16, 2013, and Debby sat shiva for her partner. The Klezbians officially formed on the last night of Donna’s shiva, when the friends came to Debby’s house to play their instruments, sing and send Donna off.

At first, the meaning of The Klezbians may seem obvious: It’s a play on words that mashes together the words “lesbian” and “klezmer.” However, not all members of The Klezbians are Jewish, not all members are lesbians and not all members can play music… very well. Playing in The Klezbians is a transformative experience for the members of the band and for the people who dance to their music. It offers founder Debby a space to remember and honor her partner of 31 years. It has given Susan, a person who often feels invisible, status in the LGBTQ2SIA+ community and a chosen family. It has given Lauren an opportunity to reconnect and rejoin with a synagogue as a queer, Jewish person. And it allows the members of the band, who are in their 50s and 60s+, to reconnect with instruments that they had not played since they were children.

For Lisa, who took up the clarinet for the first time in years while retired and bored, The Klezbians represents diversity and an absence of exclusivity. At first she played clarinet in a community band with retired “straight old farts.” When it was suggested to her that she joined The Klezbians, Lisa thought that she was being told a good joke. To Lisa’s delight, the band’s members are from diverse backgrounds: All of the members are women, some of them are Jewish, and some of them are lesbians. It is the kind of diversity that her parents’ generation would have never been able to imagine.

Klezmer music, which came to North America at the end of the 19th century with the Jewish migration and fell out of fashion by the end of WWII as Jews assimilated, is typically associated with Jewish weddings. But in the late 1970s, musicians started to experiment with the genre. Klezmer blends traditional and modern sounds, bringing together contemporary music with music connected to diasporic lands of the past. According to Jeffery Shandler, Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies at Rutgers University, klezmer plays with cultural taxonomies, challenging essentialized boundaries that define configurations of identity. It allows one to rethink the possible.

Researcher Dana Astmann dates the origins of queer subculture in the klezmer revival to the 1980s. Klezmer became a place for queer people to find a pathway into their Jewish identity. In revitalizing, shaping and reclaiming klezmer music, queer people found a Jewish medium.

In the 1980s, as the AIDS crisis became a pivotal part of queer activism, klezmer became a medium of queer pride and Jewish pride. The Klezmatics, one of the most famous and influential queer klezmer bands of their time, were founded in 1986. Their first album was called “Shvaygn = Toyt” (1988) which translates to “Silence Equals Death,” the slogan of AIDS activist advocacy group ACT UP. That album brought a dead language back to life and gave voice to a silenced epidemic. The tradition continued in the 1990s with queer klezmer bands like Isle of Klezbos, Metropolitan Klezmer and Gay Iz Mir. These bands use their names as a way to out themselves as both queer and Jewish while using traditional klezmer wedding music to advance their politics.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, The Klezbians practiced outside until it became too cold. Lauren became a member of Temple Emanu El so they could use the indoor space to rehearse; Fellow bandmates pitched in to help her pay her membership fees.

The Klezbians still perform together at the feminist seder where it all began — to which Carmel Tanaka, finally scored an invite after over a year of interviewing the Klezbians from afar. The price of admission? She had to bring her violin.

Over the years, The Klezbians have played at weddings and fundraisers. They have given queer youth and young adults a space where they can dance to Jewish, queer music. They give young Jews living in a province with a small or no Jewish community, queer and Jewish representation. And they gives voice to the work of queer Jews in their 50s, 60s and 70s who fought so that young queer Jews can bring their queerness to Jewish organizations and on university campuses. The Klezbians are the manifestation of why queer Jewish representation matters.