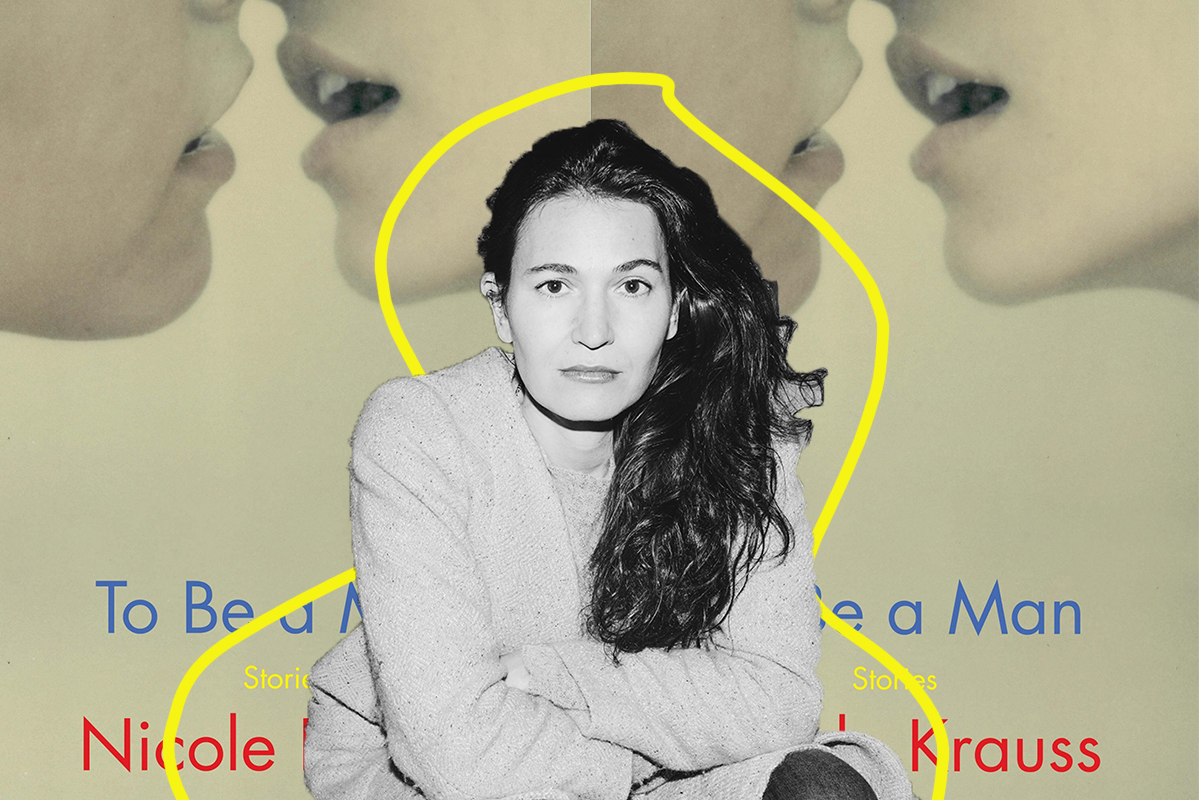

Nicole Krauss’s new story collection, To Be a Man, constitutes the writer’s first extended foray into the short fiction genre. Her novels thus far have mined various aspects of Jewish culture — particularly the role of the writer therein, and the place of the individual within history — with refreshing originality, dexterity, and brilliant psychological insight. So it is a delight, but not a surprise, that To Be a Man represents a successful continuation of this trajectory.

Ranging from a man in a post-apocalyptic refugee camp to a young woman in California working at a florist to a boarding school student in Switzerland, each character is richly drawn in Krauss’s exquisite prose, which is infinitely evocative but never stylistically excessive.

As I was reading To Be a Man, the first line of Adrienne Rich’s poem “Yom Kippur 1984” kept echoing in my head: “What is a Jew in solitude?” This collection of otherwise disparate stories seems to me to be linked by the different kinds of solitude experienced by its protagonists, no matter their physical place in the world. It feels to me like an assertion that wherever a Jew may go, from Tel Aviv to Geneva to Morningside Heights, she is always in goles — in exile.

I was eager to find out a little more about what went into the writing of this book — and the four novels that preceded it, each masterful in its own way — so I was thrilled to have the opportunity to speak with Nicole Krauss.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

I think of you as this expert literary novelist, but To Be a Man is your first story collection. I was wondering if there were any short story writers who made you think differently about writing short fiction as opposed to a novel, anyone you think of as a master of the form?

I don’t know if it’s like this for other writers, but when I’m working I’m just improvising. I feel that I’m really playing. It’s as if someone gave me an instrument, and that instrument is language, and I’m playing without knowing what’s going to come out, or what it will sound like. But I’m interested in the music that might happen, or might fail to happen, as it so often does. And whether that music comes in the form of a novel, or a poem, or a short story has never made an iota of difference to me.

I know that may be strange to say, and that I’ll continue to get questions about why this form may be different than that form. But in my experience, it’s a continuous field of expression, invention, and discovery. Some forms allow different things than others, some forms require different things than others — the novel requires years, most short stories don’t. Then again, some of these, in this collection, did. I wrote the first pages and then left them for years before returning to them. So if you count whatever subconscious work was happening during that time that I forgot about the beginnings, and didn’t think about them until I returned to them and wrote the middle and end, then I guess they took years, too.

In terms of short story writers who I’ve read and love, there are so many that I admire. I really love Leonard Michaels’ Nachman Stories. He’s just a remarkable short story writer. I’ve always loved Grace Paley’s stories, as everyone does. One of my favorite short stories written in English is Saul Bellow’s “Something to Remember Me By.” I’ve thought about that story a lot. I’ve always loved the form of the short story, and I don’t quite know why it’s the less popular sibling of the novel.

In terms of thinking about these writers you admire, there’s this phrase in Yiddish, di goldene keyt, the golden chain, that refers to the links that connect Jewish people and culture across generations. And to me that theme feels very present in your work in terms of the links between writers in both Great House and The History of Love, and definitely in Forest Dark, with Nicole’s connection to Kafka. What do you think about this idea of a literary heritage or a literary parentage? Do you think such a thing exists?

It makes perfect sense as a reader, but I just don’t feel as a writer that I think much about it anymore. When I wrote The History of Love it was still on my mind, because I was just entering into the joy of writing fiction — I wrote my first novel [Man Walks Into a Room] when I was 25, which was the first time I wrote any fiction in my life, and then wrote The History of Love at 27. So this experience of being in the realm of writing fiction and stories was only two years old.

I think that exuberance is very tangible in The History of Love.

Yes, I think there was this joy of including so many writers that I loved in The History of Love — the joy of sharing those writers and lines of theirs that I loved with the potential readers of this book of my own, which was still, then, becoming. The joy of stepping into that place of literature, which is the only place where I ever felt at home, at the hands of their hospitality, and building my own house. So of course that novel is filled with notes of affection for those writers, not just in the obvious places, like the obituaries to Babel and Kafka, but there are lines of Beckett in there, there are lines of Yehuda Amichai in there. Though now that I think of it, there is also a line of the band Bright Eyes.

I mean, Conor Oberst is a poet.

It’s filled with the things that moved me at the time, and I wanted them to have a place there. But I think that was a specific moment in time for me, a youthful one. And I’m so glad that I had it, and I’m so glad those writers are in there. But it’s not something I think about much anymore.

And often there are references that readers find that are not intentional, and one never knows how much to say about that, whether to object or not, whether to set the record straight, because at the end of the day, a reader’s experience of a work is her own, and I respect that.

But just for example, I remember people asking me if I had named Alma Singer after Isaac Bashevis Singer’s wife, and when I wrote the book, I didn’t even know his wife’s name was Alma Singer. Singer had been the last name of my boyfriend when I was 14, which is Alma’s age. It had particular significance to me that no one could have known, but instead, it was assumed to be a literary reference.

I do think there are certain writers in each of our lives who we recognize have opened paths of being for us that otherwise would not have been opened. I think there are a huge number of writers, Jewish and not Jewish, who feel that way about Kafka. He just opened a tunnel that led into a whole world where people hadn’t gone before, and since then, it’s grown wider and wider, although Kafka himself remains inimitable. So when I was writing Forest Dark, it was no longer a question of wanting to simply include a writer I loved in a book, it was that the idea of Kafka, of an alternative life for Kafka, was absolutely needed for the book to work. The notion that narratives that we accept can be narrow and confining when in reality they should be flexible and expandable, to better fit our realities, was of interest to me. And weaving into the novel a reimagining of his fate became another way to explore that idea.

Let’s talk about To Be a Man. I’m curious about the title. In the titular story there is this motif of broken ribs, and you write, “The ribs, it seemed to her, went all the way back to the beginning, and were trying to say something amid their generational confusion about what it was to be a man and what it was to be a woman, and if these things could be said to be equal, or different but equal, or no.” To me this clearly evokes the story of Adam creating Eve from one of his ribs, which we might view as a very essentialist perspective on manhood and womanhood as these two defined, separate experiences, with this implication of hierarchy as well. I wonder if you view the collection as a whole as more about being human, or if you view the collection as being about masculinity?

Well, a book of stories or a novel is never an execution of one thesis; there’s never an argument that can be boiled down and paraphrased in any way, yet of course, an overarching title is still needed.

I’ve been thinking about what it is to be a man and what it is to be a woman for a lot of my writing life. I may be somewhat unusual as a writer in that I’ve inhabited male characters and female characters almost equally throughout my books. I’ve always been drawn to and curious about inhabiting men no less than I have been curious about inhabiting women. And now, unlike when I was 25 and writing Man Walks Into a Room, I have an enormous amount of life experience. I’m sure I’ll get a lot more, but by now so many things have happened, and within those, many experiences with men: fathers, brothers, friends, lovers, the mothering of two boys.

In this collection of stories, I was often drawn to exploring men through the eyes of women. And yet, equally, I became interested in the ways young women use their experiences with men to define themselves — the way they wrestle for control over who they are sometimes within the theatre of their sexual or romantic interactions. I was also interested in how conflicted and beleaguered the definition of manhood has now become and, especially, as my boys are on the cusp of it, I have a personal stake in what it means to become a man now, in this cultural moment. I wanted to look at all of that in a way that didn’t try to resolve the many paradoxes and contradictions, but to just hold them up and look at them with curiosity and tenderness.

Certainly not all of the stories in this collection are about manhood, per se, but I think they all have to do with how a person comes to be defined, or comes to define his or herself on their own terms. It’s that struggle that is present throughout this book.

I think that that struggle in defining the self is something that really comes through in To Be a Man. Specifically, there’s this struggle to define the self despite the experience of solitude and of alienation — from one’s city, country, family, romantic partner, even from oneself. Maybe it’s just something in the mood of your prose. Or the mood I was in when I read it.

You mean lockdown and a pandemic? [laughs]

Yeah, that might have had something to do with it. But it really did make the book very timely, at the end of this year when a lot of people had to deal with the difficulties of loneliness in new and painful ways. I felt like some of your protagonists could have been comforted by reading the stories of the other ones.

That’s such a nice thought. I love that.

I just kept thinking about how the fact that everyone is alone means that no one is alone. And maybe that’s sort of trite. But these protagonists could read each other’s stories and know that there were other Jews, other people, out there whose lives might look totally different but who are similarly alone. There’s a potential for empathy in that shared experience of alienation, I think. A potential for solidarity in that solitude. And I felt that reading these stories.

I love that thought. It’s ironic to me that you say this book in particular felt to you writ through with solitude, because I remember a close and very old friend of mine who’s read everything I’ve ever written from the start — maybe this was after my third novel, Great House — said to me, “Did you ever notice that there are very rarely two people talking in your books… and there are never three people?” It made me laugh because of course one of the things I’m drawn to is the kind of thinking one does when one is alone in some sense, thrown back on oneself. It’s a more reflective and existential sort of thinking than one does when one’s busy in the thick of life.

But one can’t really think wholly about solitude without thinking about relationships, and with time I’ve found myself increasingly drawn to inhabiting the complex space of intimacy in my work. How do we connect to others, and what do we lose and what do we gain when we commit to an enduring form in a relationship, such as wife or husband or partner? Our relationships — romantic, social, familial — are the bedrock that allow us stability and a sense of belonging. But there is always compromise in every commitment. How do we balance our need for enduring forms and relationships that root us with our need for independence, freedom, and new experience? An aspect of being human is being aware that we exist to change. We’re creatures whose fate it is to evolve, who are aware of that need for change as a form of growth and survival. At every point in life, from early childhood on, a person has to balance those two conflicting interests. Do I stay or do I go? Do I remain, or leave to better become my own person? To what degree is my stability more important than my freedom? It’s difficult to have both at the same time.

As such, a lot of characters in this book find themselves on that threshold of deciding whether to stay or to go: the character in “Future Emergencies” who’s thinking about leaving her older boyfriend but doesn’t, or the character in “In the Garden” who thinks of leaving this famous landscape architect, but in the end remains loyal and stays by his side, and other characters like Tamar, or like the narrator of “To Be a Man,” who leave and embark on freedom and independence. The strain of that decision weaves through this collection as a whole.

There’s that solitude — remember the line in “The Husband” where Tamar says, “If she could reduce all of the words her patients spill in her office to a single, plaintive truth, it is that in the end everyone is alone, and the sooner one comes to terms with it, celebrates it, even, the sooner one can begin to live beyond the long shadow of anguish and anxiety.” But there’s also the question of how to square that with the fact that we all desperately need to be part of something larger than our solitude, and are so hungry for connection, for intimacy.

In an interview a couple years back, you spoke about the refuge you find from the banal within the world of fiction — the idea that everything in the world of a book matters, unlike in our world with its mundane moments and silliness and white noise. I find this view on fiction refreshing, especially when so many people talk about stories and novels as escapism in a way that sometimes devalues and discredits the way many writers are, in fact, trying to represent something truer than truth in their fiction. To me, To Be a Man is the perfect exemplar of this — it’s not escapism in any kind of fluffy sense, not an escape into another, easier world, but perhaps an escape into a more thoughtful version of this one.

Proust once wrote that the work “pre-exists us” and that we are obliged to “discover” it, as if it were a law of nature. He goes on to add that this discovery, “which art obliges us to make, is it not the discovery of our true life, of reality as we have felt it to be, which differs so greatly from what we think it is.” It’s an idea that many writers have expressed over time in different ways. I think of the realm of literature as a kind of parallel world, one governed by different rules than the one we live in. In that parallel world, everything can have meaning, and there’s a possibility for coherence that our reality here, with its disorder and its banality, doesn’t always allow for. “Characters” are people who work in the realm of literature, but who wouldn’t work — wouldn’t be live or coherent or even credible — if they walked into your room right now.

But the thing about inhabiting that parallel world, in my experience, is that whether as readers or writers, we find and make meaning there that we then have the ability to smuggle back into this reality, the one where we have to make our lives. And that meaning continues to shape and shine light on what we do here, and how we think about ourselves and relate to others. That’s the tremendous ongoing value of literature, its gift. Because if it was just this parallel world that we escaped to, when we came back, we wouldn’t have much to show for our time there. Like a Caribbean vacation, you’d have a tan and that’s it.

But instead, those of us who keep returning there, into our books, and come back into this world as we have no choice but to do every day — to raise our children, or take care of our parents, or do the shopping — we come back here with new understanding or patience, consoled or renewed by structures of meaning that help us decide who we want to be, or help us change our actions, ourselves, our lives. And in that sense it’s an incredibly powerful thing that we bring home with us, so to speak — although by now I’ve come to feel that that parallel world is more home to me, often, even than this one.

Join Nicole Krauss in conversation with Ruby Namdar and Amichai Lau-Lavie during the Z3 Experience this Dec 10-17. 70 Faces Media is a digital media partner of the Oshman Family JCC of Palo Alto, which has produced this conference since 2015.