“As a rule, if you try to explain what a good novel is about, you really shouldn’t be able to succeed, unless you recite the whole novel out loud from beginning to end,” Francisco Goldman explains to me over e-mail. “Every novel is written as a search for itself.”

Goldman continues, “It may begin rooted in a familiar reality, but then, if it’s going to be worth spending so much time with, for the writer and eventually for the reader, it leaves that reality behind. It’s partly a search for a voice, a style, a structure, a system or pattern that weaves perhaps mysterious or intuited meanings; in this novel, I worked hard to create a way to move in time, synthesizing a half century of life into the story of a five-day trip home to Boston.”

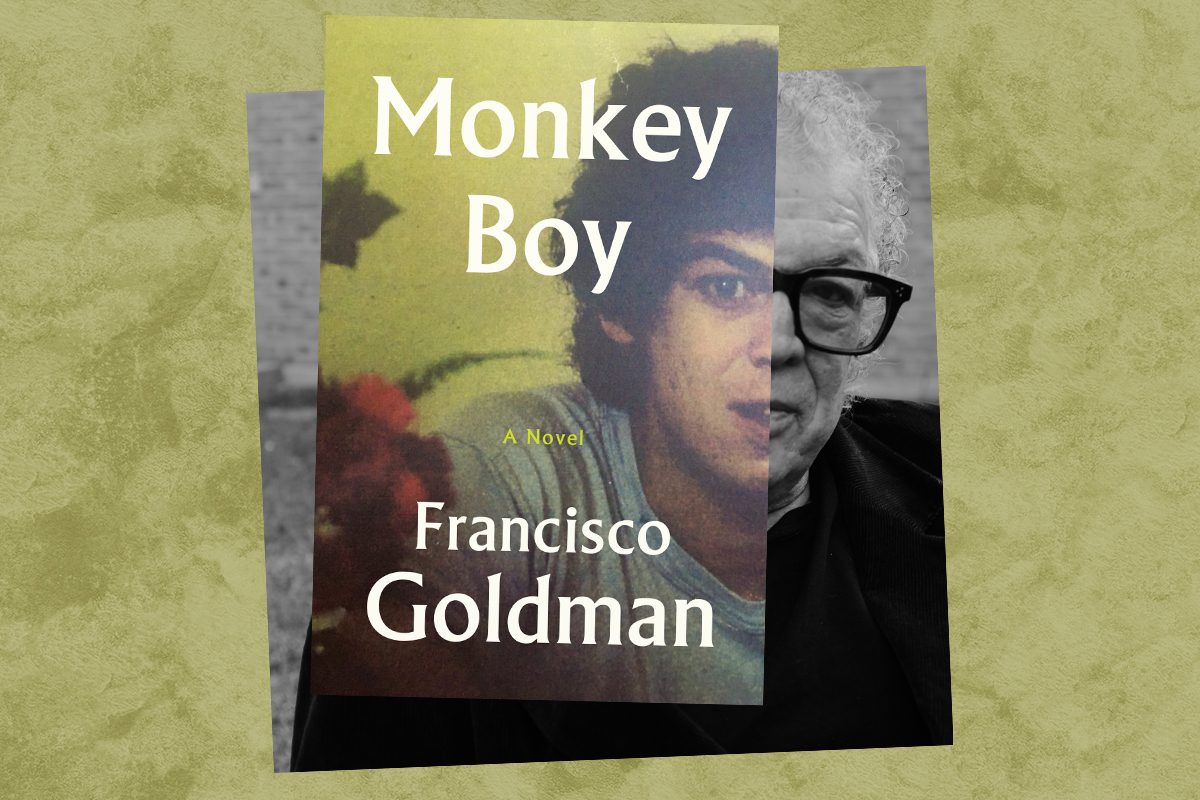

Goldman’s new autobiographical novel is a good novel by all definitions — and hard to explain, but I’ll try to give you just a taste: “Monkey Boy” is the tale of Francisco Goldberg, a man with a Jewish father and a Guatemalan Catholic mother, very similar to Francisco Goldman himself. Goldberg is returning home to Boston to visit his mother in a nursing home, and the book is set over that short journey — which brings up reflections on his past, on love, and on his complicated identity.

Goldman’s biography is similar to the fictional Goldberg’s: He was born in 1954 in Boston to a Jewish father and a Guatemalan Catholic mother, and began his career covering wars in Central America in the 1980s. He’s written four novels and two books of nonfiction, including “The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop?,” an account of the assassination of Guatemalan Catholic Bishop Juan José Gerardi Conedera. His last novel, “Say Her Name,” was an acclaimed and moving tribute to his deceased wife, Aura Estrada, a writer who died tragically in a surfing accident in 2007. In 2008, Goldman established The Aura Estrada Prize. He has received a Cullman Center Fellowship, a Guggenheim, a Berlin Prize, and so much more. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, Harper’s, the New York Times, the Believer, and numerous other publications.

Over e-mail, we spoke about what it means to be Jewish and Catholic and Guatemalan and Mexican and American, on the impulse to write autobiographical fiction, and how no one person can be “half” something.

The question of names comes up again and again in “Monkey Boy,” particularly of Jewish last names. You write, “how easy I could have made things for myself by publishing under my mother’s maiden name.” What does the name Francisco Goldman — and Francisco Goldberg — mean to you?

In the novel, that’s something Francisco “Frankie” Goldberg says while reflecting about where he fits in a rigidly tribalized literary world. He thinks about that other Frank Goldberg, who changed his name to Gehry. Would Gehry really have gotten fewer architectural commissions if he hadn’t changed his surname?

A Jewish surname like Goldberg for some reasons strikes many Americans as dissonant in a Latin American context. We see examples of that in “Monkey Boy,” like the Boston newspaper reporter who thinks he is going to expose Francisco of lying about being “half-Guatemalan,” of being a charlatan who has falsely appropriated this identity, presumably thinking there could be some benefit to himself in doing so. Now, here I will admit that this quite shocking, but also absurdly hilarious, incident really did happen in my real life.

The way I spent my 20s, and a little beyond, shaped me as a writer. From 1979 to 1991, I mostly made my living as a freelance journalist covering the political strife, the wars, of Central America — a very poor living, but I was doing what I wanted to do. I was steeping myself in those experiences in part to find my own way, and to become the novelist I wanted to be, with the very specific ambition/dream of fusing the two places of my heritage, Guatemala and the U.S., into co-equal settings in a novel. Throughout my childhood, my life was divided between Guatemala and Boston. My family on my mother’s side is Guatemalan mestizo, a mix of Mayan, Spanish and African and very traditional Catholic. My father comes from a Jewish family that immigrated to Boston from the Ukraine. All my books have been shaped by Latin American family heritage, experiences, politics, tragedies, places, people, loves, loss, and by some American influences, including Jewish ones, too.

In the opening chapter of his terrific book “White Girls,” called “Triste Tropiques,” Hilton Als writes so smartly and tenderly about a girl he loved in adolescence, the daughter of a Jew and Puerto Rican, who, though she felt herself to be entirely both, grew up feeling that in New York, at least, she really wasn’t accepted as either. I may be paraphrasing a bit, because my copy of the book is in the U.S, but Hilton writes: “The particular stupidity of New York is its need to categorize everything, and its ability to categorize only the obvious.”

Mixed-race people aren’t friends with “obvious categories;” we fall through the cracks between them. We may feel invisible, or at least not fully seen, or like perpetual outsiders. Nothing seems much more obvious, category-wise, than a very Jewish surname.

Why did you choose to write this story as autobiographical fiction? What does it allow that nonfiction doesn’t?

To quote Cynthia Ozick, “A novel, even when it’s autobiographical, is not an autobiography.” I’m Francisco Goldman; the character is Francisco Goldberg. But the novel’s present tense unfolds over a few days in the first week of March, 2007; that actual month and year, Francisco Goldman’s wife Aura was four months away from the fatal accident that would kill her. In the novel, Francisco Goldberg, on the Amtrak from New York to Boston, recalls a train trip of several years before, going in the other direction, to NYC, where he was supposed to take part in a literary event at NYU where I suppose, if it was his lucky day, he might have met a fictional Aura, just as Francisco met the real one in those circumstances. However the train is stalled for hours after an anonymous adolescent commits suicide in front of the engine, and so Goldberg misses that event. Of course, most readers, unless they have “Say Her Name” memorized, won’t realize that. So how autobiographical can “Monkey Boy” really be, regarding that present tense narration anyway?

But sure, novels don’t come out of a void, and I used the name I did, kind of a parody shadow of my own, to signal, acknowledge, even to myself in the writing, that I was taking aspects of my own life as a model. Autobiographical alter-ego novels are pretty common, as is in so many Phillip Roths, and we have Roberto Bolaño’s Arturo Belano, and the marvelous Rachel Cusk’s alter-ego-like narrator, Faye, of the trilogy. My real-life mother, named Yolanda like the mom in the novel, died in 2017, while I was well into writing “Monkey Boy.” No wonder that fictional Mamita, modeled on the beloved real one, became essentially the book’s other protagonist.

One of my favorite lines was, “Three quarters Jewish and three quarters Catholic, kept a quarter secret only for myself.” The idea of “half and half” is almost thrown away by the novel’s end, as Francisco claims both sides of his identity fully. What has been your journey of coming to terms with a hyphenated identity?

Nobody is really half this, half that. People are who they are, entirely, for better or worse, themselves. Fully Jewish, fully Catholic, that’s what the Francisco of the novel discovers, taking a cue from Natalia Ginzburg. In the novel, he finally realizes that he can fully embrace both because he is both. But the novel was also written in defiance of all categories, of confining identities to labeled boxes. So that secret quarter lives outside any box. Maybe he doesn’t even know what it is. Maybe it’s mystery and magic. Maybe it’s a joke, too. Frankie Goldberg rarely passes up any chance to slip in a joke.

What does it mean to you to be Jewish and Guatemalan and American in 2021?

I’m a third millennium American mestizo, in both the hemispheric and U.S. sense. But as the greatest Mexican singer of all, Chavela Vargas, who was from Costa Rica, famously said, “¡Los mexicanos nacemos donde nos da la rechingada gana!” (“We Mexicans are born wherever we goddamned please.”) I substitute Chilango — as people who live in Mexico City are called — for Mexican. I’m a citizen of Mexico City, my home since 1995; eventually I’ll be an official citizen of this country, too. But I remained very connected to Massachusetts and New York, and teach one semester a year at Trinity College in Connecticut. And not a day passes that I don’t think about Guatemala, from which some part of myself can never disengage.

Mestizos, which is what the majority of Mexicans are, don’t divide themselves up saying I’m this % Zapotec, this % Mayan, this % North African, part Spanish, or French, or Gringo, or whatever. All those mixes, whatever they are, make a coherent whole that we call mestizo.

Of course, in recent years in the U.S. it’s been interesting — actually it was like ingesting a not immediately fatal dose of poison every day — to be of my particular ethnic-racial-national mix. Trump descended that escalator like a toxic gas cloud to announce his candidacy calling Mexicans rapists and criminals. Hating on Central Americans was his signature campaign issue. At Charlottesville, those white supremacist neo-Nazi cretins with their flaming tiki torches, Trump’s fine boys, chanted Jews will not replace us. It was hard for me not to take those sorts of Trump Republicans pretty personally. You hate me, I’ll hate you back — on too many days, that was the feeling, and it was horrible, like a sickness.

The perhaps exaggerated tribalism of contemporary U.S. is a result of an institutional white racism that makes people of color, minorities and immigrants, band together in their own separate tribes as self-assertion-and-protection. It’s a positive stage on the way to something better, less strifeful, more inclusive, even if it does manifest at times in absurd but painful exclusions. It was heartening to see the way the Black Lives Matter marches this summer brought so many people — especially the young, our future saviors — of so many different races and ethnicities together. Nowadays we also have Vice President Kamala Harris and her gorgeous extended and gloriously mixed family to celebrate. But I won’t let my optimism run away with me. I remember weeping the morning after the 2008 presidential election because Aura and the child we were going to have were never going to get a chance to live in Barack Obama’s post-racial America.

Do you consider yourself a Jewish writer? If yes, what does it mean to be a Jewish writer?

There’s that wonderful speech Roberto Bolaño gave when he won an important Latin American literary prize, that says: “It doesn’t matter to me whether people say I’m Chilean, although some of my Chilean fellow writers would rather see me as Mexican, [and] some of my Mexican fellow writers would rather see me as Spanish… The truth is I’m Chilean, and I’m also many other things.” He goes on to say that maybe it’s the Spanish language that’s his true homeland, or maybe it’s the people he’s loved, or maybe it’s his memory, or no, maybe it’s his steadfastness and courage. And finally he says, “No, a writer’s true homeland is the quality of his writing,” but what is top-notch quality writing? It’s “the ability to peer into the darkness, to leap into the void, to know that literature is basically a dangerous undertaking.”

These words always inspire me. It’s part of the Jewish heritage, especially, to know what it means to peer into the darkness, to leap into the void, to know that life can be a dangerous undertaking. Of course lots of Guatemalans learn that too, in a very similar way. When my Guatemalan and Jewish sides speak to each other about these things, I know I have to listen very carefully.

The truth is I’m Jewish, and I’m also many other things.

Natalia Ginzburg is one writer discussed in the novel as sharing a similar mixed identity. What works do you see your story reflected in?

I love her writing, she writes with that uncanny intimacy of Chekhov. She feels especially close to me because of her divided identity, and also because of her experience of devastating personal loss and of war, and because she’s a great model of a writer/citizen concerned with inequality and justice. My favorite novel is “Family Lexicon,” an “autobiographical novel,” to be sure. Its pellucid closeness to its characters and their voices, and the way so much is suggested and powerfully sensed and felt despite going unspoken, that book especially was a special muse for “Monkey Boy.”

This is your first novel that really heavily grapples with your Jewish identity. What prompted you to explore it now?

It was a book written in part against categories in hierarchies. By the latter, I mean my own. I spent life-altering years in wartime Central America, including in close proximity to the Guatemalan genocide. You can never stop asking what you, as a writer and witness and human, still owe to a subject like that. (Think of some of our great American writers who having spent a year in Vietnam, and spent the rest of their careers mostly writing about that.)

But I was also thinking, there are so many aspects of my life that were also so important to me that I haven’t written about. What if I just write about Francisco Goldberg’s trip home? On a five-day trip home, to Boston and the suburbs, primarily to visit his mamita in her nursing home, it wouldn’t make sense for that narrator to be consumed by Guatemala in the ’80s, though it’d still be a part of who he is. But won’t he mostly be thinking about what awaits him at home, and about his past there? Childhood, the town he grew up in, adolescence, a brutal but complicated father, his sister, the other Guatemalan women who helped raised him. And won’t most of the novel be about what he does on that trip home, the people he visits with, what happens and what is revealed? And of course he’ll also be thinking about his life right now, his past problems with love, and the possibility of a new love.

And Francisco Goldberg’s Jewish parentage, on his father’s side, was a big part of his childhood and past.

What do you hope readers take away from “Monkey Boy”?

I hope that while they’re reading they lose all sense and awareness of the outside world. And that when they put the book down, the world around them and everyone in it will seem more interestingly and movingly and maybe terrifyingly alive, because the book has opened up their senses and emotions. That would be cool, if “Monkey Boy” could do that — at least a little? Also, I didn’t intend for the novel to be about this when I started, but it turned out that so many of its characters are in one way or another trying to overcome something difficult, or else they have in the past, not aspiring to be flawless or morally correct and perfect, but just trying to find a way to move ahead and maybe be better. I hope readers take something from that: inspiration, compassion, a bit of courage, some faith, maybe some love.