It’s nearly dusk by the time I’m leaving the Capital Jewish Museum, and the light is beginning to wane on F Street. About 100 years ago and 10 blocks west, the evening would just be heating up at Lafayette Park. Between the 1880s and the 1950s, gay men, Black, white, Jewish and otherwise, would rendezvous there, seeking sex, community and the necessary anonymity that the unlit park provided.

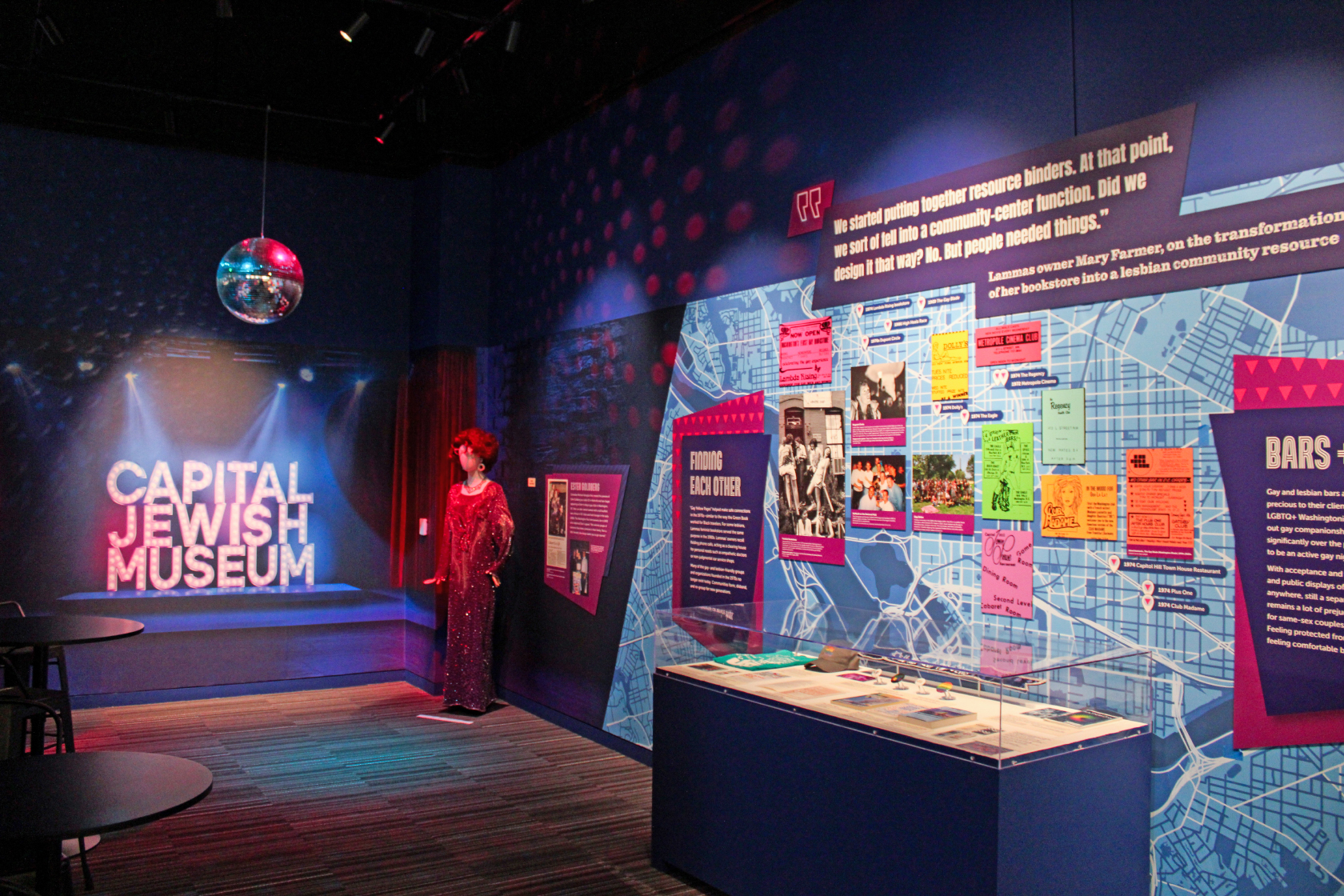

For a queer person like myself, I’m thankful that the circumstances could not be more different at the museum in 2025. Inside the gallery, an after-hours party is bustling with unapologetic queerness. It has been for the last three hours. The ground floor is a stage for D.C. drag kings and queens Chapp L’Moan, Druex Sidora, Lord Hardquaad, Onyx D. Pearl, Pariah Sinclair, Pretty Rik E and Ryder Roughly. The space reverberates Cher, Madonna, Diana Ross and Chappell Roan.

There’s face bedazzling on the first floor. On the second, there’s the opportunity to make your own button — I try my hand at copying a political button from the museum’s own collection, reading “Loud Pushy Jew Dyke,” to debatable success. Even as a somber memorial to Yaron Lischinsky and Sarah Milgrim rests just outside these walls, there’s no air of fear.

But what there is in the museum, is people. Everywhere. Attendees of all ages, some in kippot and sheitels, some donning tattoos and glittery pumps and some in both, sip lavender gin and tonics. One woman tells me she’s just there to support Capital Jewish Museum, while for the innumerable queer Jewish friend groups sitting at tables near us, it seems like a convivial night out.

Regardless of the details of what brought us here, though, we’ve all come to celebrate the museum’s superb special exhibition “LGBTJews in the Federal City.”

The exhibition, which first opened in mid-May to coincide with World Pride, Jewish American Heritage Month and Pride Month, is the first major exhibition to detail the ever-evolving story of the LGBTQ+ community within Jewish spaces in the United States. If that sounds like a niche history to you, perhaps it is. But you wouldn’t know it by the exhibition itself. The rainbow walls of the gallery overflow with the story of both the way Jews were a part of the national movement for LGBTQ+ rights on a federal level in the 20th and 21st centuries and made a home for themselves in the DMV.

The curators ponder Jewish involvement in D.C.’s early drag balls and same-sex intimacy at Jewish boarding houses like Dissin’s. They highlight Jewish-owned vaudeville theaters which served as hot spots for gay life and D.C. drag queen Ester Goldberg. And they meticulously document Jewish gay rights activist Frank Kameny’s “Herculean” struggle during the Lavender Scare to open federal employment to gay Americans and the history of D.C.’s gay and lesbian synagogue Bet Mishpachah. All of it is grounded in the Jewish principles of tikkun olam, b’tzelem Elohim and pikuach nefesh.

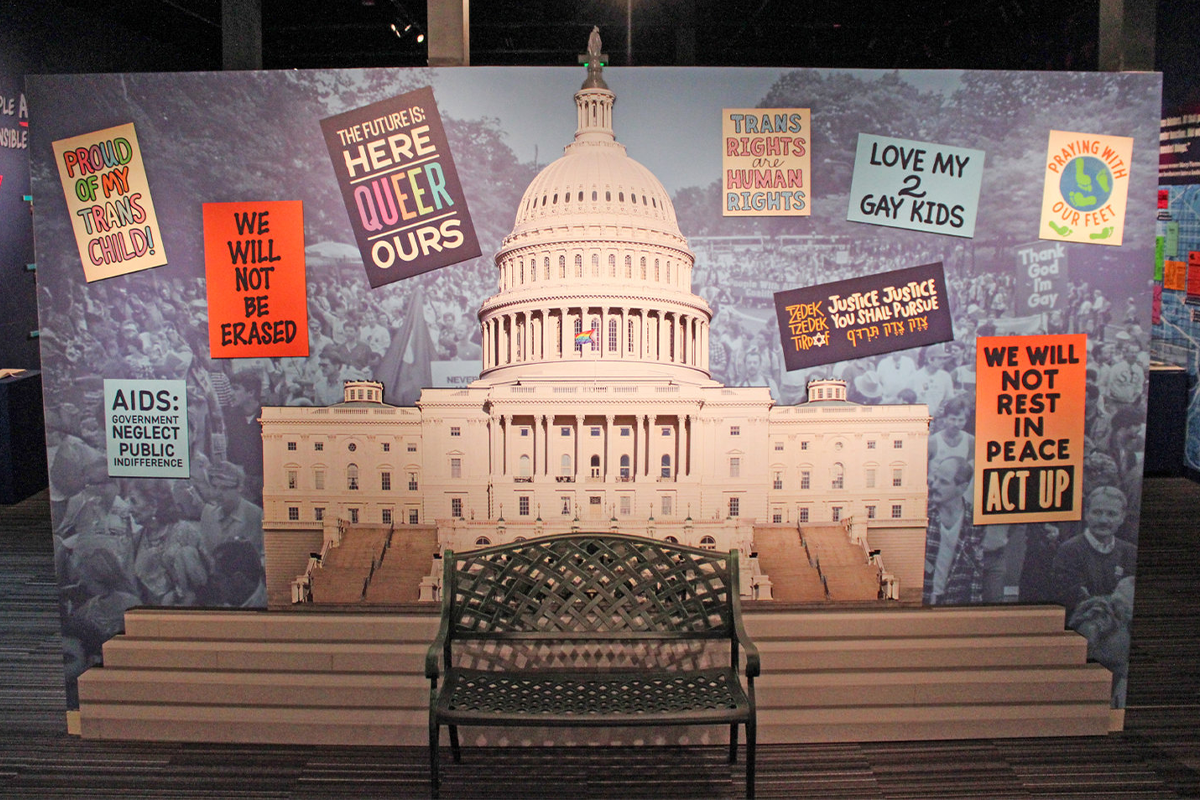

Five years ago, the museum didn’t have any queer Jewish artifacts in their collection. Curators Sarah Leavitt and Jonathan Edelman tell me this earlier in the day as they show me around the exhibit, pointing out queer Jewish classified ads from queer magazine the Washington Blade, flyers from the 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, minutes from early Bet Mishpachah meetings where some members who were federal employees anonymized themselves by omitting their last names and a ketubah Leavitt’s friends Amelia and Melanie signed in 2009. (Later, when gay marriage was legalized in D.C., the couple walked across the border from Maryland, where they lived, and were legally married in Rock Creek Park.)

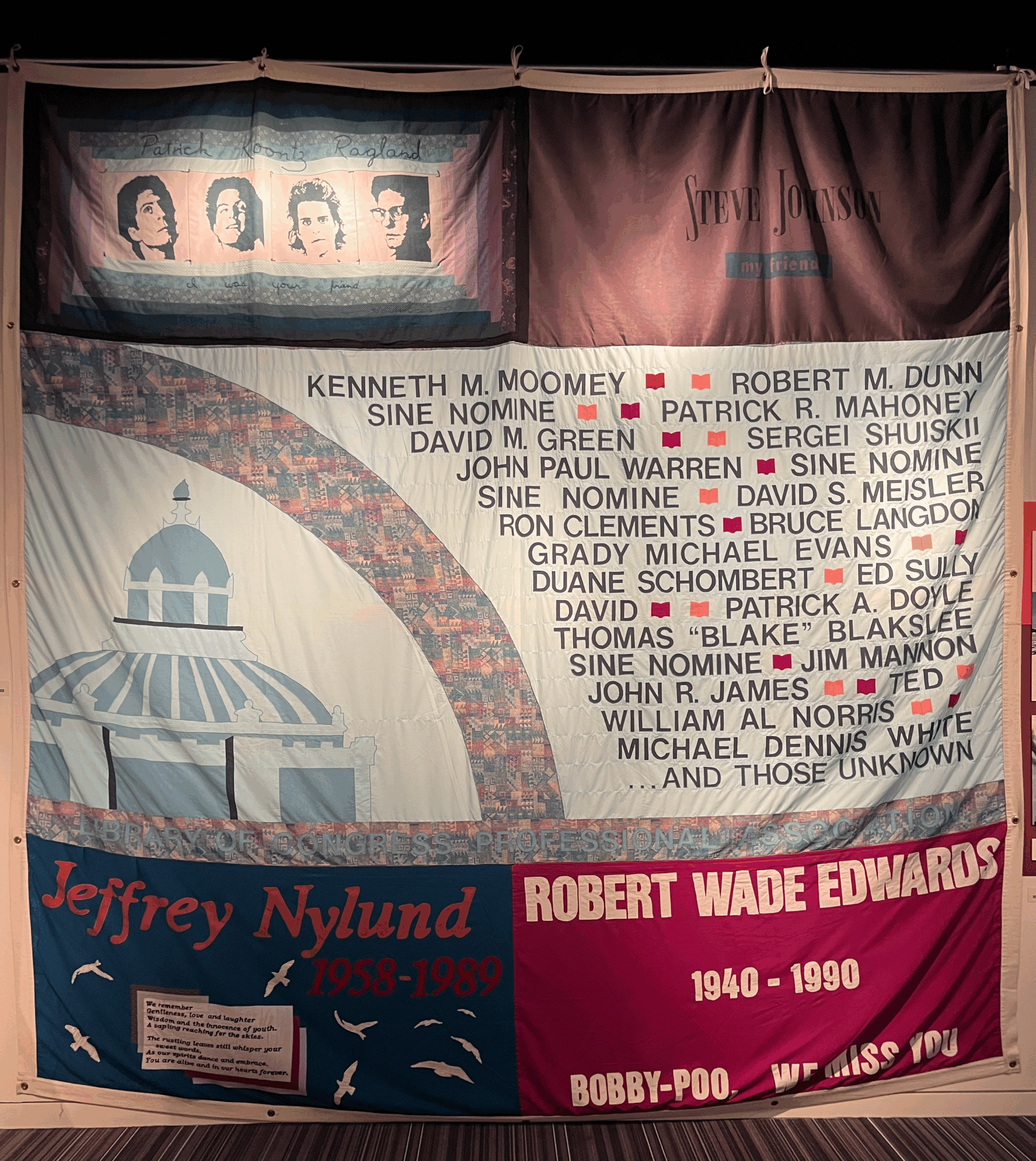

The exhibition is a testament to Edelman’s assiduousness at making sure gay Jews are reflected in the Capital Jewish Museum’s archive. Thanks in large part to him, the museum has now acquired hundreds of items including the archive of Library of Congress librarian, AIDS activist and Bet Mishpachah member David Green and, the centerpiece of the exhibition, Bet Mishpachah’s own archive. Also thanks to him and the Rainbow History Project, the exhibition includes 18 recorded oral histories from Jewish Washingtonians. The stories they tell span from heartfelt, like Jocelyn Kaplan who said she felt like she was the only person in the world who experienced same-sex attraction until she came upon a stack of Blades to hilarious, like Bet Mishpachah’s first president Joel Martin who recalled he only lasted in the role six months because he was more interested in dating, having sex and going to clubs.

Of all the poignant pieces in the exhibition, of which there are many, the most moving to me was a section of the AIDS Memorial Quilt hanging in the gallery. The largest panel on the quilt was created by the Library of Congress Professional Association in honor of their colleagues who died due to HIV/AIDS. Among the names, including some anonymized via the Latin phrase “Sine Nomine” (without name), is David Green. Green passed away in 1989 after dedicating the last years of his life to bringing attention to the horrors of the AIDS crisis. “AIDS is happening to Nice Jewish Boys like me,” Green once told a crowd at a Hillel Conference. Those words are now part of the wall text for the exhibition.

It is through exhibiting items like the AIDS Memorial Quilt that the exhibition is guided by another Jewish value: teshuvah. Later, when Leavitt and Edelman address a group in the gallery during the after-hours party, Leavitt says that it was imperative for them to pinpoint moments of queer history that does not necessarily reflect well on the Jewish community or the United States.

At the same time that the United States government was glacially slow to react to and even outright ignored the AIDS epidemic in the ’80s and ’90s, the response of Jewish institutions was extremely uneven. Testimony in the exhibition does not veer away from that or the harm it caused. So, too, does the exhibition not hide the fact that a Jewish doctor, psychiatrist Benjamin Karpman, oversaw federal mental health hospital St. Elizabeths where gay men were committed as “sexual psychopaths.” Karpman was a proponent of conversion therapy, and did public speaking about his work, including at Adas Israel Congregation’s Men’s Club in 1948. Finally, the exhibition covers the debate that raged as the U.S. Holocaust Museum prepared to open about whether to include or omit the stories of non-Jewish gay victims of the Nazis. Ultimately, Elie Wiesel advocated for their inclusion.

It’s a refreshing sight of accountability, particularly given that the week I’m at the museum coincides with the Trump administration ordering National Parks to take down signage at historical sites is “is too negative about Americans past or present.” The information targeted on these signs cover topics like slavery, climate change and atrocities the U.S. government committed against Indigenous peoples. (The Capital Jewish Museum is not run by the National Parks service, and thus this does not apply to them.) Even before this, the National Parks Service had already begun removing mentions of the transgender community from their signage, including at Stonewall.

Is telling history accurately at a museum the bare minimum? Without a doubt. But “LGBTJews” is much, much more than that. As I walk back towards Union Station to catch a train to another gay Jewish metropolis, New York, the light is now failing. But it doesn’t feel that way. Rather, I find myself riding a swell of gratitude; for the museum and its staff, for their recognition that gay people exist outside of Pride Month, for the queer community, Jewish community and the intersections of the two and that Hashem made me a loud pushy Jew dyke.

I also can’t stop thinking about something Jonathan Edelman said to me earlier in the gallery space about the process of collecting artifacts. The gay Jewish Washingtonians they contacted in the process of creating the exhibition kept seemingly every memento, he said. They still had 40-year-old pamphlets from marches, scraps of notebook paper with peoples’ names and phone numbers and synagogue bulletin board notices. Amidst many of those items, now on display in the museum, he reflected, “People were just waiting to tell us their stories.”